Here is the first sentence of my new novel: “After I finished writing my last novel, I fell into a long silence.”

And here is the opening sentence as I originally composed it: “After I finished writing my last novel, which was called Defending Jacob, I fell into a long silence.”

The narrator of that original draft, as you might have guessed, was a character named Bill Landay. Was the character actually me, the guy who wrote Defending Jacob — which is to say, not a fictional character at all? Or was he something in between — me, thinly disguised? That was for the reader to decide.

At least it would have been.

In the end, “Bill Landay” did not survive the editing process. The overwhelming response from early readers was that encountering the writer inside his own novel was more distracting than the device was worth. Several readers commented that they were thirty pages into the novel before they realized that they were not actually reading a foreword.

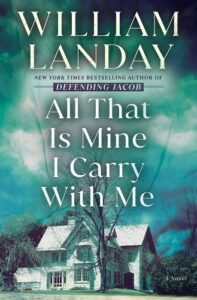

So the change was made. The narrator of the book — which is called All That Is Mine I Carry With Me — is named Phil Solomon now. Certain autobiographical details have been blurred a bit, as well, but readers will not have to squint too hard to see William Landay in Philip Solomon. Certainly my own friends and family recognize that Phil is Bill. Or mostly Bill.

I confess I am a little uneasy with the change. With every book, it seems, a few editing decisions are close calls. There is no right answer, only tradeoffs, compromises. In one respect, at this stage I trust my editors more than I trust myself. By the time these last, hard decisions are reached, I have been staring at the manuscript so long, I can’t see it anymore. And of course every writer has to fight the tendency to become defensive, to fall in love with our creations. We must learn, as the saying goes, to kill our darlings.

But in this case, I would like to pause for a moment to consider our poor, departed narrator, “Bill Landay.” Would I have been better off keeping him? Would the book have been stronger if I were still in it, unmasked?

As a reader, I have always loved the author-as-narrator device. I like when the author, in effect, breaks the fourth wall, turns to the reader, and addresses them directly.

There are different ways to play with this device. In its purest form — and bravest, I think — the writer simply drops himself into the story undisguised, as, for example, Jonathan Safran Foer does in Everything Is Illuminated or, in more of a bit part, Somerset Maugham in The Razor’s Edge. In these cases, the author-character shares more than his creator’s name, but verifiable facts of his life too, so that the story becomes a sort of hybrid novel-memoir — or seems to, since the reader cannot be sure how “real” the author is choosing to be at any given moment. An aura of authenticity is created.

Moving along the spectrum from less to greater artifice, we come to the narrator who is presented as a fictional character but who is understood, with a wink, to be a stand-in for the author, like Philip Roth’s famous alter ego Nathan Zuckerman. In fact, Roth loved to play the self-reference game. He sometimes appeared in his own novels as a thinly disguised avatar, like the fictional writers Peter Tarnopol and Zuckerman, and he sometimes appeared as Philip Roth. The device works either way. I enjoyed Roth-as-Zuckerman in American Pastoral, borrowing from the author’s own life to recreate a real-life sports hero from Weequahic High as Swede Levov, the “steep-jawed insentient Viking”; and I enjoyed Roth-as-Roth in The Plot Against America, where the author’s own family is described accurately and matter-of-factly, including his parents Herman and Bess, and the Weequahic neighborhood of Newark where he actually grew up. The effect of blending his own autobiography into both of these novels is a sense of truth that a purely fictional novel would struggle to create. We are in the uncanny valley between realism and reality.

I would include in this discussion the more conventional novelist-narrators, too, who are not so clearly self-referential but who still embody their author in a recognizable but more attenuated form. A favorite example from a favorite novel: Maurice Bendrix, the novelist who narrates Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair. When Bendrix says of the book, “This is a record of hate far more than of love,” we feel his dripping contempt because we know Greene felt it too.

So my own author-as-narrator, Phil Solomon (né Bill Landay), descends from a long tradition. Probably I will be wondering for many years whether I ought to have leaned harder into the conceit. To this day, I stew over last-minute editorial changes I made to my books years ago.

I have a sinking sense that this moment, this reading environment, is particularly well suited to the novel that blurs fact and fiction this way, both because of the too-muchness — the sheer volume of messages that bombard us all every day — and the rank dishonesty of our current culture. The tsunami of information means that it is hard to find the quiet space required to read a novel. The room is too noisy, our minds too overstimulated. The phones in our pockets tug at our attention even when they are not ringing.

Worse, with so many media gatekeepers removed, the quality of information is degraded. We live in an age of misinformation. The zone, in Steve Bannon’s memorable phrase, is flooded with shit. We’ve just had a U.S. president whose documented lies over four years exceeded 30,000. We’ve had Russian intelligence agencies plant phony news stories in Facebook and Twitter. Now we have a con-man congressman who seems to have faked his entire biography, yet remains in Congress.

In this environment, it is impossible not to be cynical. We all seem to have acquired what Hemingway famously recommended to writers: “a built-in, shockproof, shit detector.” We have been trained to filter out false information, to be always on the lookout for the con. That wariness makes it very hard to suspend disbelief, as novels require — to just go with it. Who needs novels? We’re already awash in fiction.

Our guarded mood makes the novelist’s job harder than ever. Old-fashioned realism won’t do. Not with readers who are on guard against it. You have to break through their defenses. You have to give them more, a sense of actual reality, of truth. You have to play by the new rules.

The unsettling confusion that my editors got when they read the name Bill Landay inside a novel written by William Landay? That uncertainty about “Should I trust this story? Is it true?” That is the way we live now.

As usual, Philip Roth got there first.

*