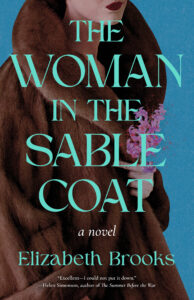

Clothes are a storyteller’s dream when it comes to showing, not telling. In Patricia Highsmith’s 1950s novel, The Price of Salt, Therese Belivet describes what Carol is wearing even before she mentions her future lover’s eyes, or mouth, or languorous walk. (“She was tall and fair, her long figure graceful in the loose fur coat that she held open with her hand on her waist.”) Carol’s appearance as a centre of stillness within the frantic atmosphere of a Manhattan department store has a lot to do with her fabulous coat, and the way she models it, and yet her poise, though striking, is not durable. That’s how it goes with coats: they are easily removed, lost, stolen or damaged. A fictional character whose essence is symbolised by a coat is very vulnerable indeed, especially if she inhabits a Patricia Highsmith novel, where moral compromise and psychic disintegration are the order of the day.

A coat without a wearer is an object of infinite possibility, begging to be filled, whether literally or imaginatively. The eponymous coat in Helen Dunmore’s, The Greatcoat, has lost its rightful owner, and when Isabel Carey finds it in the back of a cupboard, and takes to using in her freezing 1950s flat, she summons a ghost from Britain’s recent wartime past. Isabel’s airman is a dreamy and romantic apparition, unlike the red-coated figure in Daphne Du Maurier’s Don’t Look Now. Tantalised by shadowy half-glimpses, John Baxter becomes convinced that the child in the hooded red coat is his dead daughter, and pursues her through the streets of Venice—only to discover, too late, that he has been misled by his own obsessive longings.

I have forgotten the precise colour of my granny’s fur jacket, but it certainly wasn’t red; it had the natural tones of an animal pelt. My sister and I used to borrow it when we were playing ‘posh ladies.’ The fact that a living thing had been killed in order to create it contributed to its adult-ness: I couldn’t be sure whether the death of the mink (or fox, or rabbit, or whatever it was) made it more precious, or more creepy, or both.

Certainly, if a grown-up woman in a children’s book is wearing furs, she is likely to be bad news: the link between fur coats and cruelty is made explicit in the character of Dodie Smith’s Cruella de Vil, and implicit in Philip Pulman’s Mrs. Coulter and C.S. Lewis’s White Witch. The message is much more ambivalent when Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy don furs in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, as of course they do, when they climb inside the antique wardrobe and find themselves in Narnia. There are sound practical reasons for borrowing those oversized coats (it’s always winter in Narnia, under the witch’s reign), but the fact that these are adult clothes, and furs at that, is telling. They are exchanging their childhood innocence for a world of magic and violence, in which the boundaries will be blurred between wild and tame, animal and human, natural and unnatural.

A blinkered refusal to countenance the blurring of any such boundaries is the error that dooms Captain Sir John Franklin and his men, in Dan Simmon’s gothic chiller, The Terror. Trapped in the Arctic wilderness, plagued by cold, hunger, mutiny—and a semi-mythological, man-eating monster—these nineteenth century adventurers hold on to their ‘civilised’ ways with a tragic zeal. Good old woollen coats, flannel underwear and dodgy tinned food will surely see them through: never mind that the indigenous Inuit people have fur clothing (much more water-resistant than wool, and with more internal layers for trapping and warming air) and a notably lower mortality rate. There’s a beautiful scene towards the end of the book, where Captain Francis Crozier emerges from unconsciousness, having been rescued from certain death by the Inuit woman whom he calls Lady Silence. She has removed all his useless woollies, and wrapped him in furs, and he is blissfully warm and safe for the first time in the course of this gruelling novel.

Lady Silence nurses Crozier for days, while he lies naked inside those furs—and if that’s not erotic signalling, I don’t know what is, so it’s no surprise when the two become lovers. Dressing in someone else’s clothes is an intimate thing to do, and there’s a pivotal scene in Jane Eyre where our heroine stands shivering in her shawl, having rescued Mr. Rochester from his burning bed, and he offers her his cloak. It is their most intense encounter yet (“Strange energy was in his voice, strange fire in his look”) and the complexities of their nascent romance are captured in the image of the “poor, obscure” governess wearing her wealthy employer’s clothing. Yes, it evokes eroticism (the cloak that usually wraps his body now wraps hers) and love (the cloak provides warmth and shelter), but it also speaks to the darker themes of the book. Rochester’s cloak doesn’t fit Jane; it swamps, captures and claims her. Through the course of the book she must, figuratively speaking, throw it off, refashioning Rochester’s autocratic passion into a love between equals.

~

“A thing is never just a thing in itself,” wrote Jean-Paul Sartre. Just like children playing “posh ladies” in their grandmother’s old furs, novelists love to build their stories around an allusive object. An airman’s woollen greatcoat, a little girl’s red overcoat, an Inuit’s sealskin parka, a Victorian gentleman’s cloak: on the one hand, they are just bits of fabric that have been pieced together to make outerwear; on the other, they are stories waiting to be told.

Coats and cloaks will always be beloved by writers of gothic fiction, because they can speak so resonantly about the darker realities of life: absence, possession, vulnerability, desire, concealment, violence and—not least—a human dread of the cold, in all its forms.

***