In seventh grade, I said something to another girl and for that sin I was sent to a conflict resolution session. Sadly, the counsellor who was supposed to mediate had no listening skills and an agenda that made getting to the bottom of what had happened impossible. My sense of outrage over that injustice has never completely gone away and has probably driven me to write an entire crime story about conflict resolution.

For the record, what happened was that during recess someone (not me) threw a rock at a girl we’ll call R. I don’t know why the rock was thrown. It was the early eighties. We were twelve. Our middle school was afflicted with an overwhelming sense of barely controlled chaos and simmering, hormone-driven hostilities. Every single recess felt like a warmup for a riot. It was also a hotbed of racism, which the school was trying to address.

R was as tough as I pretended to be. She stormed over to where I was hanging around with a bunch of other aspiring juvenile delinquents and accused me of throwing the rock. I denied it. She called me a “stupid white b—.” I, unwisely, told her to shove something unmentionable somewhere private. (I won’t spell it out, but what I said was worse than you imagine.) R pushed me. I shoved my ice cream sandwich in her face. She punched me, resulting in a spectacular nosebleed. Ah, middle school in the eighties!

The school had already pegged me as a troublemaker —thanks to my compulsive swearing and constant stream of annoying comments. I did it for attention and to hide the fact that I had earthworm level self-esteem and was afraid of most of my peers. But the teachers didn’t see it that way. Our vice principal once told one of my friend’s parents that I was “evil”. The incident with R was deemed racist because she was Indigenous and I am not. It was decided that I needed to be confronted about my racism. But my crime wasn’t racism, it was being grotesquely inappropriate in other ways. I’d deployed the crude, sexist language I learned from my older brother and his friends in a way that was almost guaranteed to get me beaten up. My tendency to say offensive things was embarrassing but forgivable. Being racist was shameful. What I really needed was to learn de-escalation and how to avoid saying things to other people that made them want to punch me in my face.

As you might expect, the conflict resolution session was unproductive. When it was over, R still hated me, the “mediator” thought I was a liar, and I felt misunderstood, falsely accused, and increasingly worried that I was, in fact, evil. Ever since that incident, I’ve been obsessed with misunderstandings, prejudice, and how careless, cruel word choices can make almost any situation go right off the rails.

(Let me pause here to say sorry to R. I should not have said what I did. As for the counsellor, I hope she found a new line of work or at least got some more training in active listening or simply asking questions.)

Crime fiction is concerned with the ways humans violate social and legal norms and how such harms can be discovered and punished. Just as interesting to me is how all of us avoid being in a state of constant conflict with one another. After all, we’re a highly combative species. When I began to develop an investigator for a mystery series, I knew I wanted a character who was as careful with her words and actions as I was not when I was young. To this day, I tend to overreact to most things.

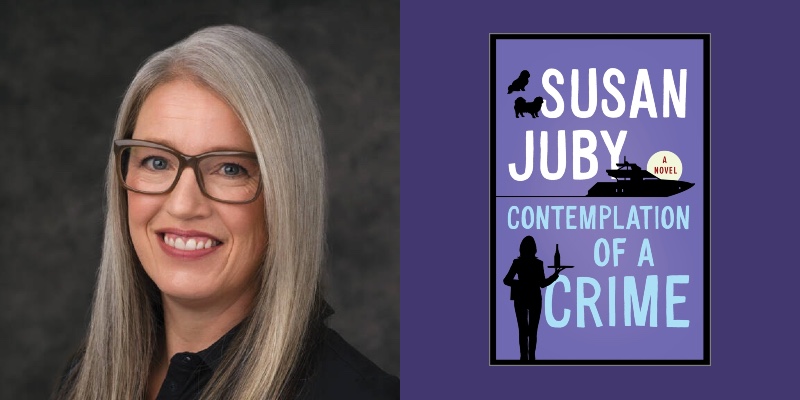

Enter Helen Thorpe: former Buddhist nun and current butler. Over the course of three books I’ve thrown all manner of terrible things at Helen and she has remained as calm, clear seeing, and slow to judge as anyone could possibly want. In Contemplation of a Crime I decided to send poor Helen to a five-day conflict resolution workshop for people on various ends of the political spectrum. Participants in the workshop include a burned-out environmentalist, a sociopathic internet troll, a far-right activist who went to the trucker convoy in Ottawa, an alleged white nationalist, a clued-out consumer, an unfathomably rich guy and Helen, his butler. When a terrible crime occurs, there are many suspects and huge reserves of distrust to go around. Naturally, Helen finds herself in the middle of it all, trying to help people resolve their endless conflicts and work together to solve the crime.

Helen views everything through the lens of a Buddhist philosophy. She believes that human behavior is highly context dependent and our experiences are influenced by beautiful qualities, such as loving-kindness, equanimity, empathetic joy, peace, and compassion. On the opposite side are the forces of greed, hatred, fear, and delusion, which lead to suffering and sometimes, to terrible behavior. This framework makes her an interesting person to delve into criminality and into social strife. She is a character who feels boundless compassion and strong boundaries. Who among us doesn’t need more of that?

As our world grows increasingly fraught, people are seeking ways we can solve our differences using religion, social sciences, psychology, psychiatry, and traditional practices. Conflict resolution programs are proliferating in workplaces, churches, schools, and at special purpose retreats. It was quite a challenge to design a program that was much more effective than the conflict resolution session I attended in the eighties.

R was a cool girl and I admired her ferocity but I never did get to know her. I wish someone like Helen had been there to help R and I sort out our differences. But since she wasn’t there, I created her—and gave her to my characters, even the bad ones, who probably need her the most.

***