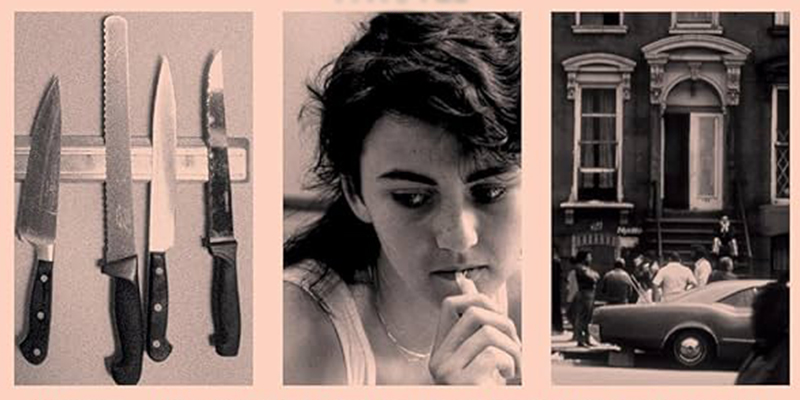

When I sat down to write a synopsis for my newest novel, Saint of the Narrows Street, I described it as “a kitchen-sink crime drama set across eighteen years in southern Brooklyn.” I’m not sure when I first heard the terms “kitchen-sink drama” and “kitchen-sink realism,” but I was attracted to that sort of storytelling before I had a name or label for it. Even as a kid, the sorts of stories that drew me in could be perceived as the constraint-ridden domain of plays, working-class tales set in cramped kitchens and living rooms and grimy bars where trapped characters, experiencing one sort of crisis or another, holed up away from the world. When I discovered that there was a whole genre devoted to stories like that, of course it appealed to me. Even better was the fact that the genre intersected with noir in interesting ways.

Typically, like noir, when folks talk about kitchen-sink realism or kitchen-sink dramas, they’re talking about a very specific place and era—in this case, it’s a British movement that spanned the late 1950s and the 1960s. As with noir, the impact of the genre reverberates through the latter half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first with many works that might be perceived as “neo kitchen-sink.” The classic school of kitchen-sink realism dealt with “the sordid aspects of domestic reality” and was rooted in a sort of social realism that was revolutionary and controversial at the time. The characters—often poor, struggling, and living in industrial areas—confronted taboo subjects (adultery, pre-marital sex, abortion, sexual orientation, and crime) that were previously off-limits in such frank ways in fiction and on stages and screens. Key features included the heavy accents these characters, often from Northern England, spoke in and the slang they employed.

Robert Hamer’s film It Always Rains on Sunday (1947), based on a 1945 novel by Arthur La Bern and starring Googie Withers, Jack Warner, and John McCallum, is often thought of as a precursor of the genre. It was a film that had a big impact on me when I watched it and one that I’ve mentioned often as key influence on Saint of the Narrows Street. Even the tagline could double as a tagline for my book: “The secrets of a street you know.” It Always Rains on Sunday looks and feels like a film noir in many ways, but it’s much more a slice-of-life, working class drama, one where escaped convict Tommy Swann (McCallum) hides out in the home of his now-married ex-fiancée Rose (Withers). It’s a story rooted in desperation, yearning, and regret.

1956 is often used as the marker for the beginning of the kitchen-sink realism movement. That was the year that John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger premiered and, as writer Alan Sillitoe (also an exemplar of the kitchen-sink movement) put it, Osborne “didn’t contribute to British theatre, he set off a landmine and blew most of it up.” Look Back in Anger is set in a claustrophobic, one-room flat in the English Midlands and focuses on a disillusioned young man with working-class roots named Jimmy Porter and his upper-middle-class wife, Alison. The harsh realism of the play—its consideration of class especially—made it the preeminent example of kitchen-sink drama in theatre and helped spawn the “Angry Young Men” movement, a group of mostly working and middle-class playwrights, novelists, and filmmakers disillusioned with traditional British society. The film adaptation of Look Back in Anger, made in 1958 and released in 1959, starred Richard Burton, Claire Bloom, and Mary Ure and was directed by Tony Richardson—I encountered the film several years ago thanks to the Criterion Channel, which sent me deeper down this rabbit hole.

Other classic examples within the genre include John Braine’s 1957 novel Room at the Top (adapted into a film in 1959 by Jack Clayton); Shelagh Delaney’s 1958 play A Taste of Honey (adapted into a film by Richardson in 1961); Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (the novel came out in 1958, the film adaptation by Karel Reisz in 1960) and The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (the short story was published in 1959, Richardson’s film adaptation was released in 1962); David Storey’s 1960 novel This Sporting Life (adapted into a film in 1963 by Lindsay Anderson); Keith Waterhouse’s Billy Liar from 1959 and John Schlesinger’s 1963 adaptation of it; Nell Dunn’s Up the Junction (1963 novel, 1965 Ken Loach BBC TV adaptation, 1968 film adaptation by Peter Collinson) and Poor Cow (1967 novel, adapted into a film the same year by Loach); and Barry Hines’s 1968 novel A Kestrel for a Knave, adapted into a classic film by Loach in 1969 simply called Kes. Kes was likely my (unknowing) introduction to the genre—I watched the film almost twenty years ago after hearing Willy Vlautin recommend it and read the book soon after. This is, by no means, an exhaustive list of examples of kitchen-sink realism—these are simply the works I’ve engaged with that have had some major impact on me and on the creation of Saint of the Narrows Street. It’s important to note that the films listed also serve as examples of the British New Wave movement, inspired by the French New Wave, which portrayed the lives of the urban proletariat.

The influence of the kitchen-sink school impacted my decision to keep the action of Saint of the Narrows Street largely focused to the cramped apartments and kitchens and dining rooms of its characters and to the dive bars they inhabit. I’ve always been interested in telling character and place-driven stories, and kitchen-sink realism has been a model for that. I love that you can often feel a place without seeing a ton of it—the place comes through the characters. And keeping things small creates tension and helps me break away from formulaic storytelling devices.

In the 1960s and 1970s, television plays became the domain of kitchen-sink realism. Mike Leigh’s BBC slice-of-life dramas made a mark on me, in particular. I first encountered these early Leigh efforts about nine years ago, prompted in that direction by Louis C.K.’s Horace and Pete (itself a sort of kitchen-sink crime drama). It is difficult, at this point, to discuss C.K. for obvious reasons, and I’ve been able to largely disentangle myself from much of his output, but the influence of Horace and Pete looms large, especially as a gateway to Leigh’s BBC work. Though I’d seen and loved many of Leigh’s later films by that point, it was an interview with C.K. where I heard him discuss Abigail’s Party that sent me down this particular road. I tracked down DVDs of Leigh’s BBC work where I could. A couple of years ago, an excellent retrospective appeared on the Criterion Channel called “Mike Leigh at the BBC” (still available as of the writing of this piece), finally giving me access to everything I’d wanted to see, identifying Leigh as “the great humanist of British cinema,” and highlighting the way these small kitchen-sink dramas “sharpened his distinctive voice and famously improvisatory process,” rooted in strong and indelible characters. Leigh’s bittersweet humor, his empathy, and his critiques of class and social structures opened up new ways of seeing and thinking about the world of working-class southern Brooklyn in the 1980s and ’90s that I was writing about.

Character-driven American films of the 1970s like The Last Picture Show and Five Easy Pieces that changed my life and perspective as a young viewer have a direct correlation to the influence of kitchen-sink realism, as does the work of one of my greatest artistic heroes, John Sayles (see Return of the Secaucus 7, for one example). I also see links to the work of Paddy Chayefsky and John Cassavetes, both lodestars for me. In attempting to portray the ugly realities of working-class lives and sympathizing with the poor and distressed, these creators helped give shape to my version of end-of-the century Brooklyn, as well.

Since kitchen-sink realism is rooted in a kind of social realism, it’s also interesting to draw lines to key works by Émile Zola, François Mauriac, and Theodore Dreiser that inspired me and are cut from the same cloth. Mauriac’s Thérèse Desqueyroux was a huge influence, as were Zola’s Thérèse Raquin and Dreiser’s An American Tragedy (and George Stevens’s adaptation of it, A Place in the Sun, one of my ten favorite films), all of which center crimes or attempted crimes. The throughline between kitchen-sink realism and noir or noir-adjacent works is desperation.

Noir is, after all, tragedy. Kitchen-sink dramas also home in on tragedies both small and profound. Violence—emotional, spiritual, and physical—hums steadily under the surface in works of kitchen-sink realism, which is why it dovetails so nicely with noir and with social realism to provide an examination of dysfunction within families and society. What happens when people—often already living on the ropes for a variety of reasons—reach the edge of sanity, have taken all they’re willing to take? The leap from boiling point to breaking point isn’t far. That’s what happens to Risa, the central character in my book, a good woman married to a bad man, who winds up paying in blood for a necessary decision made in the heat of the moment.

I should say that, ultimately, my work borrows tenets from the kitchen-sink movement but pushes it forward in my own direction through a blend of melancholy noir melodrama, neighborhood mythology, and dark humor. Whether or not my work qualifies as kitchen-sink realism or not is a question for readers, but there’s no doubt it’s a major strain of DNA in Saint of the Narrows Street, providing me with so much inspiration for the characters and conflicts and textures of the world of the story.

***