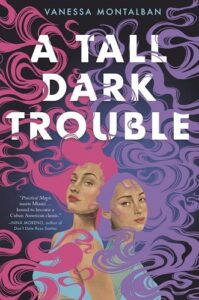

As most Cuban Americans would tell you, Viva-po-Ru (Vicks VapoRub) can cure anything from a cough to a fever, but when it comes to matters of the soul, you’re better off visiting your local curandera tossing shells or cards out of her shed. Then, be prepared to make a trek to your local botanica with a very specific set of instructions. I can’t tell you the number of times I heard a magical remedy prescribed growing up. The neighbor is having marital problems, so you offer to make an appointment with your tarot lady. Or, while in the bakery line waiting for your morning pastelito, you might overhear that someone’s mother-in-law placed a “brujeria” on them and they’re in desperate need of a despojo. Magic, spells, or rituals were such an inherent part of my experience living in a heavily dense Cuban American community, so it felt like second nature to weave magic into my debut novel A Tall Dark Trouble following a Cuban American family of brujas.

Each of the three main characters in my story must determine how magic and religion play into their beliefs, figuring out how their worldview is informed by or in contrast to the traditions, folklore, and gifts of their heritage. A Tall Dark Trouble is a dual timeline story that explores the political turmoil of 1980s Cuba through the lens of Anita de Armas and Miami’s landscape in 2016 through the points of view of teenaged brujas Delfi and Ofelia. In Cuba, Anita’s mother is part of a secret cult that guards the infamous Cuban comandante using a twisted sort of magic. But Anita finds solace in her religious practice, discovering that her powerful lineage isn’t only a tool to be used by others, but a gift that can possibly gain her freedom, though at a cost. In contrast, Delfi and Ofelia Sanchez, are the embodiment of my experience growing up in Miami. In current day Miami, the twins have always been warned away from magic by their mother. Their only experience with their mother’s religious practice has been peripheral. But as their powers develop and lead them to uncovering a murder, the twins capture the attention of some dangerous brujos. Unlike Anita, the twins don’t have the magic-based knowledge necessary to protect themselves. Because sometimes we need to know where we come from, what our ancestors went through, in order to guard us from future danger.

The concept of ancestral magic is more than just a fantasy element. It’s a magic that comes through the gift of stories, of practices, and rituals that children of the diaspora inherit from their parents. It’s a magic that’s been comprised of pain, colonization, exile, and strength. With my debut, I wanted to explore different ways this inherited power could be both a burden and a gift, and how often our diasporic heritage is built on silence.

Magic through Anita’s point-of-view is presented more as a burden. Anita’s power makes her a target and a tool for her mother’s cult and the Cuban government, so naturally, Anita resents her magic. Instead, Anita finds solace in the Santeria religion. For a brief overview, Santeria is a syncretized religion in Cuba derived from the African Yoruba and Catholicism during the slave trade. For Anita, Santeria was a connection to her grandmother and a sign of resilience against the regime. Because of the political oppression and religious restrictions of 1980s Cuba, Anita’s beliefs and practices were sequestered to the shadows. But because of her beliefs, her new friends, and accepting her powers, Anita would soon find the strength to fight for freedom.

Through the points-of-view of the Sanchez twins, Delfi and Ofelia, I wanted to capture what it means to have magic as a second-generation Cuban, living on the periphery of Santeria and Caribbean beliefs, split between ancestral teachings and a Westernized upbringing. Magic, for the twins, is an inherited gift they don’t know how to control. The rules, the teachings of their ancestors are lost to them which often happens in diasporas. Children of migrations are cut away from their family’s roots, transplanted to new soil before they’ve had a chance to truly learn what it means to bloom.

It was important to me to set my novel in my hometown of Miami, where I grew up visiting the botanicas that could be found on nearly every street corner, shops where you could often buy herbal spell kits, receive a spiritual consultation, or send a package to Cuba all in one place. Miami is a melting pot of Latinidad, just as Santeria is a melting pot of different traditions. Miami has its own culture, and as it was in my case, it’s the culture the twins connected most with—an in between place that feels as much Westernized America as it does Caribbean islander.

There’s also a type of magic and mystic energy wrought in these communities that, like me, the Sanchez girls of A Tall Dark Trouble grew up with. Although, unlike my characters, I haven’t had psychic visions of a murder or been hunted by a group of brujos, but the magic of whispering spirits and otherworldly intuition is one that doesn’t feel as far-fetched.

Like the Sanchez twins, I also had a practicing parent. Weekends spent at my dad’s house exposed me to many facets of Santeria worship. His altar was always kept in a small, enclosed cabinet by the front door, and the tureens for his orishas guarded by Saint Lazarus were given a special place in the living room. But my proximity to Santeria didn’t necessarily come with knowledge—curious, I’d ask my father about the santos or the altar, or the green and yellow beaded bracelet he wore because he’d received his mano de orula (an initiation ceremony within the faith). But my father was secretive, answering reluctantly with what I assumed was almost a sense of shame. My father was adamant that I should explore the religion for myself when I was older and when I could decide whether it was something I felt called to explore. So I respected my father’s secrets and eventually realized it was never shame he felt, but protectiveness over a practice that had been conceived from oppression and that to this day still faces countless prejudices.

The truth is I grew up outside a lot of the traditions of the Santeria faith to truly know what it means to leave a country behind with only its resilient religion as baggage. The harsh realities of growing up in Cuba were heard in snatches through family stories, and passed down through customs and superstitions too ingrained into me to dissect and examine. Though the stories of exile, corruption, and dictators were more than stories, they were my loved ones’ reality, but I would never, thanks to them and their bravery, experience the loss of everything for a chance at freedom. I wouldn’t have to board a sinking shrimp boat in ninety degree weather over shark infested waters to leave my collapsing home. Still, the memories and traumas can at times feel hereditary, even if there is a disconnect. And my experiences straddling cultures is one my parents have experienced differently. Yet every story deserves to be told because silence in the diasporic communities only perpetuates the idea of shame and disconnect, rather than pride and empathy.

My hope was that by creating the stories of the Sanchez women, woven from my own experiences, I could begin to bridge the two generations and come from a place of empathy when looking at past mistakes and inherited traumas. To add one more story to the millions that deserve to be told. Writing this novel, exploring these three perspectives, allowed me to take a step back and realize how vast these diasporic experiences are. Helped me realize that sometimes when you’re straddling multiple cultures, it leaves you stretched thin. You’re constantly reaching for the peak of what each culture represents, the epitome of that identity. And like my characters, I’m learning that identities can look so different from one another, and it’s within those experiences, perspectives, and stories that we find what it means to be ourselves.

***