Here is a short list of things that are easy:

–Brunch.

–Turning on the television for your children instead of reading to them.

–Looking at your phone and checking some vacuous app some deem crucial.

–Sleeping in.

–Eating too much.

–Making love.

And so on and so on. The “easy” list is extensive and if done in excess becomes boring. As the saying goes: everything in moderation.

Here is a slightly longer list of things that are not easy:

–Going to brunch and pretending to enjoy yourself.

–Turning off the television and convincing your children that reading is better.

–Not looking at your phone for an hour (try it, prove me wrong).

–Awaking early to be productive.

–Eating less red meat.

–Making love.

–And, of course, with a bullet, writing well.

I’m not an essayist, so forgive me if this essay isn’t that good. I’m trying to enter into this subject lightly. The subject of conveying menace in literature. Sustaining the malevolent. Delving into the places one does not like to find themselves within. With an amount of irreverence however, and hopefully levity, I can come to some kind of conclusion. Or at least a palatable commencement.

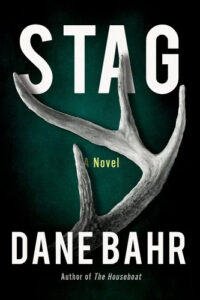

When I was writing Stag my mother-in-law was dying. I loved her very much as everyone in her world did. She was the kind of woman most women want to be. My wife and I and our very young sons went to Colorado for Christmas that year. And during that Christmas we watched her deteriorate and when my wife told me she was going to stay with our newborn son, to be with her mother in those final terrible days, I said of course. The day Tor (he was three at the time) and I left, mom staggered from her chair, looked at my wife, her only daughter, and in a tone so clairvoyant it was almost incoherent, said: That’s the last time I am ever going to see them.

For the next month and a half Tor and I went through life together. It was January in northwest Washington. It was dark and it was cold and it was wet. We spent most of our free time skiing. But to get to the mountains you have to travel a stretch of road where people lived in squalor amongst the vines and moss and tin shacks with woodsmoke leeching from bent stovepipes. It’s a stretch of road that terrified me and still does. Having Tor in my custody, being the one to keep him from harm, I’d dwell on the macabre at night after I’d put him to bed. We’d pass those ruinous little places tucked into the woods and I’d think about the fear a little boy might feel being left there and the horror a father would comprehend having left him behind, and all the evil things that often befall the truly innocent.

Stag has nothing to do with that dynamic though. Nothing to do with a father and a son. But it was a vivid emotion that prevailed within me till the book’s conclusion, and every morning when I sat down to write and I had to reenter that morbid place where there seemed nothing left of hope, where evil reincarnate was allowed to move freely, haunting what it will, it brought me pause. I have never felt such consternation while working on a book. It’s a novel I’m still fearful to read aloud.

Which is all to say, in anything I write, I’m examining my fears in an attempt to bring about some levity. Not to the work itself, but my own life. To make everything that scares me easier to face. It’s not cathartic, exactly. It might not even be healthy. But to obsess over a story and the characters and the prose and the struggle, getting the dialogue and the lighting and the smells and the sounds, takes a generous amount of empathy. And that, I think, is healthy.

I envy the brunch crowd sometimes. I too like to laugh. But sometimes you have to climb deeper to avoid the darkest places. Sometimes that void beyond reach or reason glows brighter than one might think.

***