When my co-editor Salem West and I began work on Crime Ink: Iconic, we knew we wanted to do more than compile a strong anthology of crime fiction—we wanted to make a statement. In 2023, Jeffrey Marks’ study of thirty major crime anthologies revealed that out of 517 stories, fewer than one percent were written by LGBTQ+ authors. That sobering statistic underscored how few opportunities queer crime writers are given to contribute to the genre, and how urgently we need to correct that imbalance.

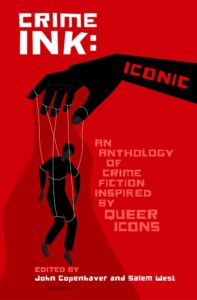

Crime Ink: Iconic brings together more than two dozen of today’s most exciting LGBTQ+ crime writers to create new stories inspired by queer icons—from James Baldwin to Christine Jorgensen, Dolly Parton to Billy Strayhorn. The result is a kaleidoscopic collection spanning cozy mystery, noir, psychological thriller, procedural, and more. These stories speak to legacy, resilience, and the subversive joy of seeing queer lives at the center of a genre that has too often sidelined them.

I posed five questions to several contributors, inviting them to talk about their chosen icons, their creative process, and the challenges and pleasures of writing short queer crime fiction. What follows is their candid, passionate, and often surprising insight into writing crime that’s as bold and multifaceted as the icons who inspired it.

Contributors

Ann Aptaker — Lambda and Goldie Award-winning author of the Cantor Gold novels, and contributor to Best Mystery and Suspense 2025.

Diana DiGangi — Author of legal and financial thriller Last Chance Chicago.

Margot Douaihy — Author of the award-winning Sister Holiday Mystery series, including Scorched Grace and Blessed Water, both named Best Crime Novels of the Year by the New York Times.

Renee James — Author of seven novels, including BeatNikki’s Café, a finalist for the Joseph Hansen Award for Crime Fiction.

Ann McMan — Two-time Lambda Literary Award winner, author of fourteen novels and two short story collections, and laureate of the Alice B. Foundation for her outstanding body of work.

Jeffrey Round — Author of the Dan Sharp mysteries, Bradford Fairfax mysteries, and the award-winning war novel The Honey Locust.

Q1: What do you think crime fiction allows us to explore about queerness that other genres don’t?

Diana DiGangiL The crime genre offers a lot of metaphors that resonate with the queer experience. When the protagonists are fighting or investigating a crime, they’re often going against establishment forces to do so, for the sake of additional conflict. Detective protagonists are often individuated and offbeat in ways that are queer-coded, even when they’re straight. They have to see the world in a way others don’t. As a kid, much of my love for the Sammy Keyes series came from the fact that she was a straight-talking tomboy like me.

Crime and queerness both break with the standard social contract, and obviously queerness has a long history of being criminalized. That feeling of being in violation of something as a member of a certain order, and the constant need to know where the people around you stand, can sometimes feel akin to an involvement in organized crime. The difference is that you don’t choose your queerness—nor does it harm others—which is a more vulnerable and painful position to be in.

Ann Aptaker: The sharpest difference between queer crime fiction and other genres—especially mainstream crime fiction—is our relationship to the law and law enforcement. For so much of our history, we have been treated by the law as criminals just for who we dance with, who we kiss, who we love. When crime comes to our community, either when we’re preyed upon or when we commit crime, the reaction of law enforcement—the police, the courts, the penal system—has historically been more harsh than when these institutions deal with crime in the heterosexual world. This dicey relationship with the law, our victimization by law enforcement (frequently with the approval of segments of the American public), is inherent in queer life, and thus in queer crime fiction.

Renee James: All storytelling is conflict, and a story revolving around a crime has built-in conflict on several levels—who did it and why? How are the main characters affected by it? And what’s going to happen because of it? That gives the author a lot of opportunities to create tension and sustain storytelling velocity, and I think it also creates a fallow field for internal character struggles, which are so striking in the best queer fiction. Queer characters can struggle with internal conflicts common in our community—like moral choices, regrets, conscience, self-image, and self-doubt—while also dealing with a crime.

Ann McMan: One thing could be the fact that, so often, crime stories involve societal misfits—or perceived ones. Many times, our characters live on the periphery or in the shadows—and are often ignored, disregarded, and unseen. They are nearly always misunderstood, and their motivations are often viewed as sinister or mercurial. Sound at all familiar? Queer crime writers can explode these myths and allow our characters to move out of the shadows—acceding to roles other than antihero, sociopath, or cultural deviant.

Jeffrey Round: It’s a way to explore the sexuality of my characters, whether it be a futuristic New Form Human, as in Transubstantiation, or a contemporary queer private eye, as in my Dan Sharp mysteries, allowing me to create a character who isn’t above blurring personal and professional boundaries when it comes to his clients.

Margot Douaihy: Crime fiction’s DNA lives in narrative driven by questions and transgressions—questions of “justice,” power and powerlessness, transgression, ambiguity, normativity. (Everything, really.) To paraphrase author Erin E. Adams, mysteries are about breaking the world apart and seeing if or why we should put the world back together as it was. That’s why crime fiction is an ideal genre for queer narratives that refuse to accept an elusive “normal” as a baseline or a reference point for life. I am keen to write and read crime fiction where queer characters can be messy and messed up and fully dimensional, rather than cheap tokens or martyrs.

Queer crime fiction should be required reading right now, to catalyze resistance to autocracy. Fabulous resistance, I might add. Queer and trans people have been and continue to be criminalized around the world and at home, so we have a lot to say about this matter. We’re living through an appalling retreat to conservatism right now, in the US, where there is a felt reality of threat for many LGBTQ people. Trans people are being scapegoated and pilloried because it is politically expedient. The word diversity is essentially being outlawed on college campuses and in businesses. Sigh. So, crime fiction’s focus on “justice” begs us to ask vital questions, like who makes the laws and who do our laws protect? Why? Where there’s tension there’s energy—and queer crime fiction thrives on productive tension.

Q2: What drew you to your queer icon—and how did they shape your story?

Jeffrey Round: I have always had a morbid fascination for artists who die young. It sprang from an early interest in guitarist Jimi Hendrix and blues singer Janis Joplin. Later, I heard of James Dean and Wilfred Owen. I recall the first time I saw Dean, in East of Eden. I came away from that screening staggered by how much his performance moved me. I felt an almost overwhelming grief on learning he had died years earlier at the age of 24. The same was true for Owen when I read his poetry and researched him. You can’t come to terms with the deaths of such people. It weighs on you, sometimes for years, as in my case.

Margot Douaihy: Radclyffe Hall’s The Unlit Lamp gutted me. Yeesh, that birdcage scene at the end. It’s so bleak, and so well rendered. It captures something recognizable, both textually and subtextually, about the way queer women can get trapped by expectations and circumstances. It also narrativizes the contortions of breathing behind cage bars and the slow soul murder of watching your dreams flicker out. Hall’s literary aesthetic is precise, clean, and erudite. The dialogue’s sharp and pacey. But it’s also got really great riffs of low-key satire. It’s witty and snarky within the third-person POV; we can feel some Modernist valence, with a value of interiority. (The Unlit Lamp was published one year before Mrs. Dalloway.) It also offers narrative cartography for false choice points. AKA women have no real choices, and that sucks. The character of Joan sacrifices the academy and the job she wanted for familial duty, but it leads her down a dead end, and that’s an emotional blueprint for Sam in “High Hit Area.”

Renee James: I never saw Laverne Cox act, but I read interviews with her and witnessed her leadership in the transgender community, and I formed an impression of her as someone who has overcome a lot and still has style and grace. Those were the qualities I wanted for my heroine, Sydney, along with the scars that come with the experiences queer people endure when they come out.

Ann Aptaker: I’ve always loved Billy Strayhorn’s masterpiece, “Lush Life,” written in 1933 but first recorded by Duke Ellington’s orchestra at a Carnegie Hall concert in 1948 with singer Kay Davis. Though the song doesn’t mention queer life explicitly, the song’s mix of melancholy and sophistication, both in its complex melody and lyrics, feels like an expression of our queer experience. The music’s change of key reflects the uncertainties we face as queer folk. I felt this way about the song even before I learned that Strayhorn was himself gay—a gay Black man who had to carefully navigate the hipster-macho world of jazz musicians in the 1930s and ’40s. The song’s meshing of beauty, elegance, and sadness was the chief influence on my story, “Heartbreak Alley,” providing the story’s tone and mood.

Diana DiGangi: The idea to reference Sally Ride came from my girlfriend, who works on Hubble, and the entire story grew from there. Originally, my mind had gone to either white-collar crime or organized crime, which are more familiar to me, but I was getting nowhere in terms of ideas or potential icons. With an astronaut in mind, I started having a lot of ideas about how to blend crime and the space exploration aspects of sci-fi, which I’ve always wanted to do. Space gives you that locked-room element. I greatly admire Sally Ride, and she’s one of the icons of the golden age of U.S. space exploration, so invoking her fit my story’s doomer themes of 21st-century decline and over-reliance on tech.

Ann McMan: Dolly Parton is more than a queer icon: she’s an American icon—one who, bless her, is known for being extremely queer-positive. For me, she was a natural choice—particularly given her special focus on literacy and making higher education not only affordable but free for residents of her home state of Tennessee. As of June 2024, Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library has given away more than 244 million books.

Q3: What’s unique—or especially challenging—about writing short crime fiction inspired by a real-life queer icon?

Renee James: I confess, I conceived my plot premise—a young woman on a dating app date with someone she knew before she transitioned—before I began thinking about an icon. Settling on Laverne Cox was a fairly straightforward matter of matching age, beauty, and intellect. The biggest challenge was deciding about Sydney’s race; in the end, I didn’t think I could write her as a Black trans woman in an authentic way, so I made her Caucasian.

Margot Douaihy: Short fiction demands a unique cadence and focus. And while I have a lot going on in this short noir, I want to cut to the bone. My aim was to translate some of the crackling tension and exigent questions that I felt when I read The Unlit Lamp into a contemporary story rooted in the experience of a Lebanese-American lesbian. I needed some modern equivalents for Hall’s constraints, like economic necessity and geographic isolation replacing some of the social mores of life for women in 1924 England. The trickiest part was avoiding overdetermined, overcomplicated plotting, which is hard with a story of double-crosses and spirit photography.

Ann Aptaker: On the one hand, I want to be respectful of the life of the real person who inspired the story. On the other hand, there’s the danger of being so tethered to the real person’s life or influence that the story might not blossom on its own. In “Heartbreak Alley,” I reference Strayhorn’s song “Lush Life” and incorporate its mood, but I let the protagonists—Josie McGraw and police Sergeant Thomas Sloan—deal with the murder they’re faced with in their own ways. For Josie, it’s achingly personal. For Sloan, it’s a job, and an education.

Jeffrey Round: What I found most challenging was bending biographical facts to serve the needs of the story. I needed to make the invented versions of the characters’ deaths plausible. When we take liberties with real-life characters, especially ones who are well-known, we know we are going to face critical scrutiny, especially from other fans. I needed to feel not so much that it did happen this way, but that it could have happened this way in the speculative world I created.

Ann McMan: For me, the hardest part was to make sure Dolly was omnipresent in the story without coopting the plot. I wanted to emulate her by permeating the story with one of the themes that matters most to her: childhood literacy. Dolly Parton cares about books—and so do we. So, I worked hard to weave her in and out of the narrative in organic ways—like naming the main character Jolene. And also, by having the intended murder weapon be engraved with her iconic quote, “Find out who you are and do it on purpose.” And that, after all, stands as a mantra for all of us who write queer fiction.

Q4: Did you face any unexpected challenges or surprises while writing your piece?

Ann McMan: I did! The intended murder weapon in the story ended up being a piece of hand-thrown pottery that I actually own. And the fact that the urn contains a quote from Dolly Parton? It’s one of those great gifts the universe sometimes tosses into our paths. You know … the kinds of happenstances that cannot be scripted or predicted. They just present themselves at exactly the right time.

Renee James: A 3,000-word short story is like haiku compared to writing a 90,000-word novel. It sounds easy, but it isn’t. Every word and sentence has to work hard, and the need for refinements and edits seems never to end. It’s like crafting a bonsai tree instead of just letting a Scots pine grow in your yard.

Jeffrey Round: This was the first time I have attempted a piece of speculative fiction, so it was all a challenge! I wanted to emulate the best writers I’m acquainted with in what is, for me, a new genre, while still keeping to the rules of good noir and mystery writing.

Margot Douaihy: I never could have predicted how strongly Maine set the pace. The setting dictated the story’s rhythm and even some plotting. Hyperlocality and the brutal, rural isolation set a peculiar meter and emotional syntax from the jump. In small towns like my fictional Kendall, Maine, secrets taunt out in the open, hiding in plain sight, and everyone’s up in your business. Choices are limited. The rich folks control everything. And if you’re stuck outside in the cold too long, or you walk out too far on the ice, you’re screwed. Landscape’s a character, a red herring, and a clue.

Q5: What’s one queer crime novel (besides your own!) that’s changed how you think about the genre?

Renee James: I’m currently reading Margot’s book, Scorched Grace. Her writing is very literary and dramatic. She shows us the vast potential for complex, charismatic characters in crime fiction, and the narrow line between investigating suspects versus passing judgment on others. The latter point—judgmentalism—is a disease in our society today, in my opinion, and she deals with it masterfully.

Ann McMan: I can think of several—and they are all part of the same series. The first novel is The Talented Mr. Ripley by Patricia Highsmith. In these books, she gave us the ultimate antihero. A villain we grudgingly find ourselves mesmerized by, and rooting for. These novels exploded our ideas of what was right and acceptable. Tom Ripley became an unhappy talisman—a predictor of where we were headed both culturally, psychologically, morally, and politically. Ripley was a precursor to who we were fated to become. These novels are seminal works of queer crime fiction—and of fiction in general.

Jeffrey Round: There were two: The Tallulah Bankhead Murder Case by George Baxt showed me that mysteries can be fun and funny, while Michael Nava’s The Little Death showed me that I could write about the personal lives of my protagonists in a genre that often eschews the personal and emotional lives of private investigators.

Diana DiGangi: William Goldman’s Marathon Man. First, it surprised and heartened me that a mainstream bestselling thriller from 1974 could feature a gay deuteragonist who fits the classic action hero mold, and that the romance between him and the antagonist could drive the plot as much as it did. Doc, a closeted Cold War spy, is living a double life in these two major ways, which are designed to mirror each other and overlap within the context of the Lavender Scare. The ability to hide your sexuality and the pain of doing so are aspects of the gay experience that I think about a lot, and I see a lot of overlap there with the crime genre—especially in conspiracy thrillers, where innocent protagonists are often forced to violate their personal ethics to escape persecution from a crooked system.

Margot Douaihy: Just one? I can’t. I have to say two. My hot take is that James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room is one of the greatest crime novels ever written. (Literary scholars, come at me.) The book starts with our narrator, David, telling us that Giovanni’s about to be executed: “I stand at the window of this great house in the south of France as night falls, the night which is leading me to the most terrible morning of my life.” The novel then takes us on a journey of David’s life, how he met Giovanni, and cascades of nested questions, pleasures, and pains leading up to the death sentence.

And I’d point to Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt as inviting me into a new way of thinking about genre. Sure, there’s a gun in the novel. There are lawyers and bad guys. Folks are on the run. But the crime itself is love. Or at least desire. Carol and Therese’s relationship is dangerous—so much more dangerous (arguably) than theft or some other kind of criminal act. The stakes feel higher than a whodunnit.

Even without a dead body or a murder, the novel is asking crucial questions about justice, and it sinks us into the genre hallmarks of suspense, disorientation, paranoia, and surveillance. Also, it’s widely touted as one of the first novels with a happy ending for the queer ladies—though a nuanced victory, of course. Queer people break some social contracts, and they beat the odds. Transgression with reparative effects. Some good trouble, as it were. We need more of it.

***