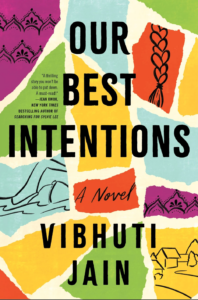

I wrote Our Best Intentions, a novel anchored in the suburbs of the Northeast and featuring a fifteen year old protagonist, while 7,900 miles from New York and two decades after my own freshman year of high school. It was only after becoming an expat and approaching middle age that I was able to articulate an honest, at times nostalgic, at other times critical, perspective on living in “progressive” American suburbia and the agony of being an adolescent girl.

I’d moved to Johannesburg, South Africa in 2015, having lived in the Northeast (Connecticut, Boston, New York) for most of my conscious existence. The reasons for my move, how I navigated a different country and new continent, and my reflections on life in South Africa are topics for another day. But suffice it to say, my move dislodged a decade and a half long writer’s block. I was writing again – or trying to. By 2019, I’d resolved that I needed to satiate my lifelong desire to author a novel, and I was on the hunt for inspiration. The problem was, I was looking in all the wrong places.

I obsessed over the adage that I should write what I know and felt tortured by it. I was scrutinizing my immediate surroundings for a spark, an idea, telling myself I needed to write about life in South Africa, but the problem was, I didn’t know life in South Africa. Not really, anyway. I was living a bubble-wrapped expat life in a country where I didn’t speak any of the local languages or have a deep understanding of the sociocultural context, where most of my friends and co-workers were similarly expats, and where I remained more attune to mainstream America than I did to mainstream South Africa – if indeed there is such a thing in this truly multicultural country. Writing a story set in South Africa intelligently seemed hopeless.

Fatefully for me, things fell into place – or at least clicked – during a trip home to the U.S. that year. The plot of the novel was in conceived on a spring day in 2019 following a conversation I’d had in an Uber with a driver of South Asian descent. I was on my way from JFK going to my parents’ house in Stamford, Connecticut and making jet lagged small talk.

My driver told me about a series of violent incidents that took place in the public high school of the Westchester suburb where his children attended school. He told me about the resulting outrage from local families about the decrease in the quality of their public school and the questions from parents about if the alleged perpetrators were properly enrolled in the school district. I found myself both listening and spinning: My imagination began to sprint with thoughts and questions about the coded language that I anticipated was being used by self-proclaimed progressive parents when describing the influx of minority students into this fancy school district; about the backgrounds and backstories of the alleged perpetrators; about the inherent unfairness in access to quality public education in America; about navigating controversies on race as an Indian American – brown, but not consistently identified as a minority; about ethnicity and class, and who is viewed as belonging somewhere; about memories of my own teenage discomfort with being different in my relatively homogenous and affluent home town in Connecticut. As we drove through the dense Connecticut woodlands to my parents’ home, a plot was taking shape.

I wrote Our Best Intentions in a sunny suburb of South Africa, often writing from a garden full of palm trees or while snacking on fresh mangoes and litchi during North American winter. While my immediate surroundings couldn’t be more remote than the Northeast riverside town in which my novel was set, the discordance didn’t stop me. In fact, it fueled me. I knew the fictional town I was writing – its local coffee shop, the centurion oak trees, the summer humidity mixed with the smell of fresh cut grass, the ubiquitous town rec center, even the hibachi grill run by karate instructor at aforementioned rec center – by heart.

Being far away from the place I was writing about – and having a stark contrast to it immediately around me – forced me to clearly articulate the sights, sounds, and smells and sensations of Kitchewan, all alive in my head, on a page. I consciously constructed each detail, because living somewhere so different made me hyper-aware of each detail.

Similarly, I wrote Angie reflecting on adolescence as a woman – a woman who has thankfully grown comfortable in my own skin, but who can recall, often ruefully, the unease and self-consciousness of being just the opposite as my younger self. In knowing, through my present day reality, there is another way of being, that one can nurture and develop self-confidence, it was easier to write character who is unsure of who she is or who she wants to be, inexperienced with ethical grey areas, interested in doing the right thing, but not always sure what that is, or if she’s brave enough. In the case of Angie, temporal distance gave me the license to be honest without feeling personally vulnerable.

My novel is embedded in a high school in Northeast suburbia, but I’m not sure that I would have been able to write it without being able to zoom out – physically and temporally. Distance allowed me to see both the macro and the macro – the overarching sentiments and themes I wanted to convey and also the minutiae that makes it real – the pit in one’s stomach, the fishbowl of high school hallways, the distortion of sound underwater, what’s said and what’s left unsaid. What’s more, writing from a distance allowed me to reflect in a way that can be difficult, if not impossible, when entangled in the subject matter in real time.

My novel isn’t about adulthood in South Africa, but it is with thanks to Johannesburg and to the fine lines around my eyes that I was able to write Our Best Intentions, capturing both the forest and trees.

***