Some of the most sinister villains never break the law.

They dress in quiet luxury. They drink good whiskey in leather club chairs. They conduct business over linen-draped tables in restaurants with perfect views and white-gloved service. None of this looks like crime. It looks like success.

And they have succeeded. They’ve solved the oldest problem in crime: how to get away with it.

They don’t need to hide their actions because they’ve engineered systems where guilt can never quite be proven—a hard shell of compliance, layers of complexity beneath it, and a protected center where accountability can’t reach. Everything is legal, licensed, and defensible. Justice exists in theory, but not in practice.

Crime fiction keeps returning to this kind of villain for a reason. In a world where harm is increasingly legal, institutional, and insulated by process, these systems feel undefeatable. Outrage has nowhere to land. By placing a human architect—a bad guy with a face and a name—at the center of these systems, crime fiction gives readers somewhere to aim. Even when justice is incomplete, it offers relief from the feeling that power always wins.

Take Richard Roper, the arms dealer at the center of John le Carré’s The Night Manager. Roper doesn’t conceal his operation, he fragments it. Manufacturing, logistics, financing, and sales are all legally insulated, spread across borders, and fronted by licensed intermediaries. Every piece of the enterprise is defensible on its own, and no single thread can be traced cleanly back to him.

When the story begins, Roper is already known to intelligence agencies on both sides of the Atlantic. But taking him down would disrupt intelligence visibility, require fragile international cooperation, expose years of institutional tolerance, and invite political fallout. Roper understands this. He has made himself indispensable to the very systems that might otherwise stop him.

As a result, the effort to dismantle him exists only at the margins of the justice system. Jonathan Pine is pulled in because he has already lost someone to Roper’s world. Angela Burr persists not because she has the backing of MI6, but because she refuses to accept the institutional decision not to intervene.

What follows is an inversion of power that crime fiction returns to again and again: the villain moves openly, protected by legitimacy, while the protagonists are forced underground—meeting in abandoned buildings, running off-the-books operations, lying to colleagues, committing crimes of their own in service of stopping a greater one.

This is not a quest to build a case that will survive a courtroom. It is an attempt to crack the system by targeting one tangible point: the man at the center.

That distinction matters. In stories like The Night Manager, justice no longer means arrest, trial, and sentence. It means removal. Roper’s organization is too distributed, too legally insulated, to be dismantled piece by piece—but it does hinge on him. Eliminate the central figure, and the system collapses. The protagonists’ methods may be compromised, but the target is not. The reader never doubts who deserves to fall.

What makes this systems-based model so unsettling is how closely it mirrors reality. In Empire of Pain, Patrick Radden Keefe chronicles the Sackler family’s role in the opioid crisis—a catastrophe engineered not through criminal conspiracy, but through regulatory mastery.

Purdue Pharma was licensed to manufacture OxyContin. Doctors were legally targeted and incentivized. Marketing strategies stayed just inside the bounds of what regulators allowed.

Like Roper, the Sacklers didn’t need to hide. Their system was designed to survive scrutiny, with responsibility distributed so broadly that criminal liability became nearly impossible to assign. Everyone knew where the harm was coming from. No one could make the consequences stick.

The pull of Empire of Pain is not only outrage, but scale. Like The Night Manager, it stages a modern David-and-Goliath story: immense wealth and legitimacy on one side, and a handful of investigators, journalists, or whistleblowers on the other. Power is centralized, insulated, and self-perpetuating. Resistance is precarious, underfunded, and often futile. The tension doesn’t come from wondering what happened—it comes from wondering whether anything can be done about it.

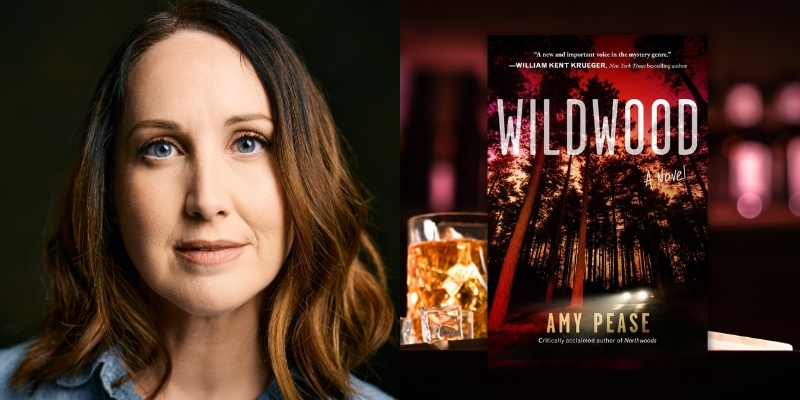

In both stories, power is protected by regulation, jurisdiction, and institutional complexity. In my crime novels Northwoods and Wildwood, the shield is something more intimate: trust. Specifically, the trust we place in healthcare systems and the people who operate within them. We assume that those tasked with healing, treating, and protecting the vulnerable must, by definition, be acting in good faith.

My protagonists are small-town law enforcement, underestimated precisely because they lack scale, polish, and institutional power. They don’t have access to intelligence backchannels or off-the-books operations. What they have is persistence, skill, and a refusal to accept that legitimacy equals innocence. My villain’s greatest protection is not secrecy, but belief—the assumption that someone who appears benevolent must be harmless.

That assumption points to the deeper emotional problem these stories are wrestling with. In real life, systems this large don’t invite confrontation; they invite resignation. We learn how harm is normalized, how institutions protect themselves, how responsibility is dispersed until outrage has nowhere to land, and then we’re asked to carry that knowledge without resolution.

Crime fiction pushes back against that impulse by refusing to let harm remain abstract. It insists on identifying an author. Someone who designed it. Someone who benefits from it. Someone who can be named and watched. Even when justice is partial or compromised, that act of concentration matters.

Crime fiction doesn’t promise solutions. What it offers instead is orientation. By giving wrongdoing a human shape, it resists the idea that power is too diffuse to challenge or too vast to confront. It reminds us that power is made by people—and can be challenged the same way.

***