For years, I was obsessed with true crime. I grew up on a steady diet of Forensic Files and Dateline, watching with my mother as crimes were distilled into hour-long puzzles with tidy solutions. I was mesmerized by the supposed certainty of science—fingerprints, bite-mark evidence, timelines snapping into place—and by the genre’s implicit promise that truth, if pursued hard enough, would always prevail.

What I didn’t yet understand was how often those stories relied on omission, simplification, faulty forensics, and narrative sleight of hand—and how easily the same storytelling instincts that make true crime addictive can, in real life, help put innocent people in prison.

As I got older, podcasts took over the true crime genre, feeding my curiosity in a more immersive, intimate way. Each episode posed the same thrilling question: Did they arrest the right person? The stories unfolded neatly, stripped of legal complexity and emotional consequence. The victim and the accused were kept at a safe distance, which made it easy to consume these cases as puzzles rather than reckonings with real harm. Given all this, I often joke that it’s no surprise I grew up to become a criminal defense attorney.

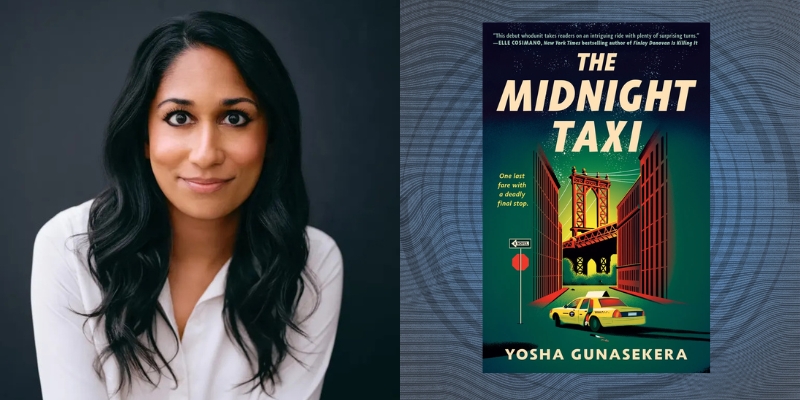

Like Siriwathi Perera, the protagonist of my novel The Midnight Taxi, I assumed that years of consuming true crime would give me a leg up. When Siri, a New York City cab driver, is arrested for the murder of her passenger—seemingly the obvious and only suspect—she turns to the rules she’s absorbed from true crime to investigate her own case. She looks for motives, timelines, inconsistencies. She tries to outthink the narrative forming around her. Is she successful? Partially. And that partial success mirrors my own experience: true crime can teach you how cases look, but not how they actually work.

True crime promises truth right there in its name. In some ways, it prepared me to engage with horrific facts day after day, to sit with violence and uncertainty in ways others might find intolerable. It introduced me to the twists and reversals criminal cases can take—especially cold cases, which now make up much of my docket. Today, I work as an innocence attorney investigating cases where my clients were wrongfully convicted and are serving decades in prison for crimes they did not commit.

Once I began representing real people, I started to see the danger embedded in the genre’s storytelling instincts. True crime thrives on narrative momentum. Evidence crystallizes around a suspect. Tension builds. Resolution follows. In court, that same narrative drive can be catastrophic. Once law enforcement settles on a story, uncertainty shrinks. Alternative theories vanish. Conflicting evidence is reframed as noise rather than treated as a signpost toward another suspect.

True crime often mirrors this process, locking onto a single narrative and carrying it through to a clean ending. The reader is left with answers instead of questions—and sometimes an innocent person is left behind bars.

One of the main differences between the cases I handle and the true crime I once consumed is that my job is not to craft a compelling arc. My goal is justice: freeing an innocent person, not entertaining an audience. In real life, there is rarely a neat conclusion. Cases remain messy. Facts refuse to line up cleanly. Truth resists compression.

As Siri comes to understand in The Midnight Taxi, the way investigations unfold in true crime—engineered for maximum dramatic payoff—is rarely how things play out in reality. As an attorney representing the wrongfully convicted, I spend my days undoing damage caused not only by bad evidence and flawed investigations, but also by the narratives sold to juries, judges, and the public. Stories have power. In the criminal legal system, the wrong story can ruin a life.

One of the most persistent myths reinforced by true crime is the assumption that police and prosecutors are always on the right side of justice—that they get it right. In reality, prosecutorial misconduct is one of the leading causes of wrongful convictions. Sometimes that misconduct is blatant: the intentional suppression of exculpatory evidence.

Other times, it’s quieter and more insidious—tunnel vision, confirmation bias, a refusal to revisit early assumptions. In Siri’s case, critical information is withheld from her defense in the early stages, severely limiting her ability to fight the charges. That scenario is not fictional exaggeration; it reflects patterns I see repeatedly in real cases.

Another problem lies in the stories we tell about the people who become ensnared in the system. We assume that someone arrested by the police must have done something wrong. Arrest becomes shorthand for guilt.

In Siri’s case, the investigation goes awry in part because law enforcement refuses to pursue other leads in the crucial hours after the murder—the most valuable window for uncovering the truth. This kind of investigative failure is disturbingly common. Once a suspect is identified, the search for evidence often becomes a confirmation of guilt, rather than a search for what actually happened.

True crime frequently reinforces this logic, inviting the audience to participate in the narrowing of possibility. We’re encouraged to weigh evidence not with curiosity, but with confirmation in mind. We look for clues that fit the story we’ve already been told. In doing so, we replicate the very mindset that leads to wrongful convictions.

Finally, true crime often fails to center the people most harmed by the system—not only victims, but also the wrongfully accused. In The Midnight Taxi, if not for her attorney, Siri would easily feel as though the case were something happening to her rather than a process in which she has agency. Many people in the criminal legal system lose their voices entirely. Decisions about their lives are made in rooms they never enter, based on stories they never get to correct. Their humanity is flattened into plot points.

This erasure has consequences. When we treat these cases as puzzles rather than as human tragedies, it becomes easier to accept collateral damage: years lost, families fractured, lives defined by crimes someone else committed.

At its best, true crime can expose systemic failure, challenge official narratives, and even help free the wrongfully convicted. But that requires a shift in how we consume it. Ethical true crime resists easy villains and clean endings. It treats uncertainty not as a flaw, but as an invitation to look deeper. It centers the humanity of everyone involved—not just the victim, but the accused, the convicted, the forgotten.

As readers and listeners, we should demand stories that ask harder questions than who did it? We should ask: Who benefited from this narrative? What evidence was ignored? Whose voice is missing? Because the real danger of true crime isn’t that it makes us curious about violence—it’s that it can teach us to mistake a compelling story for the truth. And in the criminal legal system, that mistake can cost someone their life.

***