In novels (if not in life) there is something very pleasurable about being taken for a ride. You might argue that all fiction does this by luring the reader into a temporary belief that made-up people and events are entitled to their time, energy and emotions—but the effect is definitely heightened when an unreliable narrator is part of the mix.

The lack of reliability may be innocent: a result of the narrator’s own limited perspective. It may be knowing, but well-meant, if they have a particular agenda to push. On the other hand, the unreliable narrator may be a deliberate manipulator, wanting nothing more—or less—than to mess with the reader’s mind.

The unreliable narrators in this list range from guardians of moral virtue, to enchanting spinners-of-yarns, to out-and-out psychopaths.

Notes on a Scandal by Zoë Heller (2003). Notes on a Scandal is the story of school teacher, Sheba Hart, and her affair with a teenaged pupil. It is also—or perhaps it is really—the story of a very twisted friendship, as told by Sheba’s colleague and confidante, Barbara Covett. Barbara, a lonely woman in her sixties, who has struggled all her life to maintain proper friendships, is deeply drawn to her younger, prettier co-worker, and an unequal friendship begins: superficial on Sheba’s part, increasingly obsessive on Barbara’s. When the illicit teacher-pupil affair becomes a public scandal, Sheba’s life implodes, and she becomes a pariah. How ‘fortunate’ then (inverted commas very much intended) that Barbara is on hand to provide comfort and protection. Notes on a Scandal is a dazzling exploration of the blurred border between love and cruelty, and it is Barbara’s voice—insinuating, needy, touching, domineering, sinister—that generates the story’s power.

Darling by Rachel Edwards (2018). [SPOILER ALERT] Some unreliable narrators have an iffy smell about them from the get-go (Barbara, from Notes on a Scandal, is a case in point). Others seem so trustworthy and endearing that the reader will take their hand without a second thought, and allow them to lead the way. Rachel Edwards’ eponymous Darling belongs in the latter category. Everything about Darling’s story puts us squarely on her side: the racism she experiences as a British-Jamaican marrying into a white family; her bravery as the mother of a seriously ill child; the sheer warmth, passion and generosity of her voice. It’s so easy to forget—in fact, at the hands of such a skilled storyteller, it’s virtually impossible to remember—that this is the version of events Darling wants you to hear, and not necessarily the truth.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847). At first glance, Jane looks like the opposite of an unreliable narrator. Even among the ranks of virtuous Victorian heroines, she is notable for her honesty and moral courage, and the novel gives no sense at all that Charlotte Brontë wants her readers to doubt her heroine’s account (no slippery post-modern shenanigans here, thank you very much). However, I think this makes Jane the perfect illustration of the thesis that there can be no such thing as a reliable first-person narrator. Unlike the omniscient third-person narrator, who is able to dictate the terms of his or her fictional universe to the nth degree, the first-person perspective is necessarily limited, as in real life. Other characters’ secret thoughts, feelings and motivations remain mysterious. It may be true that Aunt Reed is a shallow, cruel and unimaginative ogress, and nothing more … but what would Aunt Reed’s take be, if she were pushed to give her own account? What about Grace Poole, or Blanche Ingram, or little Adèle? Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea (‘mad’ Bertha Rochester’s famous riposte) is proof of just how much scope the unreliable narrator—even one as high-minded as Jane Eyre—leaves open for new perspectives, which may both challenge and enrich the original narrative.

The Magus by John Fowles (1965). If you don’t enjoy being blindfolded and spun round and round on the spot by an unreliable narrator, then The Magus is one to avoid. Nicholas Urfe is a young Oxford graduate, teaching English on the Greek island of Phraxos. He makes friends with an eccentric recluse, Maurice Conchis, who starts playing bizarre tricks on Nicholas—a series of psychological games which become ever more weird and elaborate as the story progresses. As Nicholas loses his grip on the truth, the reader does too. There were so many turning-points in this novel where I thought, “Ah ha! Now I get it!” only to have the rug whisked from under my feet … again.

The Murder of Roger Ackroyd by Agatha Christie (1926). [SPOILER ALERT] Christie’s novel caused controversy on publication, by breaking the first ‘rule’ of the Whodunnit, as codified by Ronald Knox a couple of years later: “The criminal […] must not be anyone whose thoughts the reader has been allowed to know.” The story, concerning a series of murders in the sleepy English village of King’s Abbot, is narrated by Poirot’s mild-mannered sidekick, Dr. James Sheppard. In a shock twist, at the very end of the book, the killer turns out to be—yes, you guessed it, but only because you’re reading a piece about unreliable narrators—Dr. James Sheppard. Brilliantly, Christie does not allow her narrator to record a single falsehood; his slippery omissions and evasions are enough to conceal his guilt. Christie may well have pushed the possibilities of the unreliable narrator to their absolute limits with Roger Ackroyd, but she made it work, as only she could. In 2013, the Crime Writers’ Association called this novel, “the finest example of the genre ever penned.”

A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess (1962). In this futuristic satire, a subculture of teenage gangs is terrorising the population of a grimly-envisioned England, and the state will stop at nothing to subdue them. The sociopathic protagonist, Alex (“Your humble narrator”), tells the story via a mixture of English and Anglo-Russian argot called Nadsat, which Burgess invented for the book. In the first edition, no key was provided for the slang, and the only way for the reader to try to make sense of it was by total immersion in the narrator’s hideous mindset. At the heart of the book is the question of whether it can ever be right for the state to recondition someone’s mind by force, however delinquent they may be. Burgess’s answer would seem to be no—that freewill trumps everything—but it’s interesting to wonder what the answer would look like from the perspective of a different character.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov (1955). Words can be a toxic hazard, as demonstrated by Nabokov’s infamous masterpiece. The novel is told from the perspective of paedophile and murderer, Humbert Humbert, and follows the course of his sexual obsession with a twelve-year-old girl named Dolores Haze (upon whom he imposes the more fantasy-friendly name, Lolita). Humbert marries Dolores’s mother in order to gain access to the child, and is widowed shortly afterwards. Stepfather and stepdaughter then embark upon a cross-country road trip, during which Humbert’s abuse of Dolores becomes increasingly physical, and his efforts to retain her interest increasingly frenetic. What makes the book difficult, as opposed to simply repellent, is Humbert’s artistry as a narrator. He flatters, seduces and wows with his flamboyant prose style, to such an extent that the reader is in danger of being brought on side: willing to condone the actions of a monster, because the monster spins his yarn so well.

Life of Pi by Yann Martel (2001). Martel once said of his most celebrated novel, that it can be summed up in three phrases: “Life is a story”; “You can choose your story”; “A story with God is the better story”. Pi, a young Indian boy washed-up on a Mexican beach, tells of the Pacific shipwreck in which his family and their migrating zoo were drowned, and of the subsequent two hundred and twenty-seven eventful days he has spent at sea, in a lifeboat, with only a Bengal Tiger for company. It is a compelling tale of friendship, faith, beauty and survival—but Pi’s rescuers refuse to buy it. He offers them an alternative version, in which there is no magic; only a drab ordeal of suffering and brutality. Since neither story can be proved or disproved, Pi’s rescuers (and, by extension, Martel’s readers?) agree to believe the first.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain (1884). A child narrator is always going to have a somewhat skewed perspective, if only because he or she is still at the stage of discovering who they are, and what they think, in a world run by adults. For the modern reader of this American Classic, the story of Huck’s relationship with Jim, the runaway slave, is likely to be the most important thread in the book. Mark Twain’s agenda is (by the standards of his time) anti-racist, and yet in order to illustrate the entrenchment of nineteenth century attitudes, he allows Huck—our hero—to feel desperately conflicted about the rights and wrongs of helping Jim (Miss Watson’s ‘property’) to win his freedom. It’s an interesting—and challenging—example of an author in conflict with his own narrator. From the reader’s point of view, it’s just as well that Huck is a child, trying to navigate an upside-down moral universe. If he were an adult, we might be less willing to forgive his ambivalence.

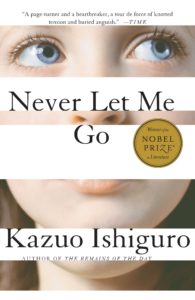

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005). This is an almost unbearably intriguing novel, which reveals the true nature of its narrator, and the horror of her story, very gradually. Kathy is a Carer, whose job is to look after organ donors, and she spends much of the book reminiscing about her childhood and the nice-but-peculiar English boarding school that she attended with her friends, Tommy and Ruth. So far, so benign, and yet … the words Kathy uses to describe her situation (the teachers at her school are known as ‘guardians’, for example, and the patients who die in her care are referred to as having ‘completed’) don’t feel quite right. It becomes increasingly clear to the reader that Kathy is employing euphemisms, and the effect is deeply sinister. Never Let Me Go is a journey of self-discovery in the most heart-breaking sense, and Kathy is an unreliable narrator because the world in which she lives is doing its utmost to blind her to her own identity.

***

–Featured image: Francesco Mazzola, called Parmigianino.

Self-portrait in a Convex Mirror. 1524