Charm isn’t the right word, but there’s something about New York as it was in the 1970s that still holds a grip on us today. We all have our reasons. Depending on taste, it might be the low rents, the lunch counters, the music, the art scene, or maybe just the sense that the city was more connected to its past and people then, and though it was a difficult place to live, the ones who managed could look all comers and questioners in the eye and tell them to go screw, or in the more genteel parlance of Bobby Short at the Carlyle, “I happen to like this town.” The latest vision of the city in the bad-old days comes Sundays this fall, with HBO’s The Deuce, created by David Simon and George Pelecanos. The series focuses on Times Square in the 70s, long before Giuliani’s Adult Entertainment Ordinance, at a time when the area was awash in sex and sleaze, a magnet for hustlers of all stripes. For the writers’ room, Simon and Pelecanos have assembled a murderers’ row of literary talent, including Richard Price, Megan Abbott, and Lisa Lutz, not to mention Pelecanos himself. The Deuce might well earn a place beside The French Connection, Taxi Driver, and Dog Day Afternoon as another seminal portrait of a city on the brink.

But in addition to Sunday night viewing, why not look to the writers of the era, the ones whose gritty fictions first helped define what was happening here during that turbulent decade? Postwar crime fiction was largely an urban-set phenomenon, and in the 70s, New York City played host to some of the era’s defining stories. The spirit of the 60s had turned ugly, poverty and violence were rampant, and paranoia was in the air. The same themes that energized American New Wave cinema were found in the pages of latest thrillers and noir meditations. Reading them now, the attitudes toward race and sex often seem outdated or downright offensive. But you’ll also find the seeds of many of the issues still gnawing at our city and society today, from police brutality to the widening income gap to institutional racism and misogyny.

Here are ten crime novels that helped to define New York City in the 1970s.

Judith Rossner, Looking for Mr. Goodbar

Probably the best, most complex crime novel of the decade, Rossner’s Looking for Mr. Goodbar actually began as a non-fiction story for Esquire. The piece was about Roseann Quinn, a New York City schoolteacher murdered on New Year’s Day in 1973 by a man she’d brought home from a bar. The magazine killed the story, supposedly so as not to unfairly influence the murderer’s trial. Rossner decided to change the names, expand the scope, and turn the article into a novel. In Looking for Mr. Goodbar, “Theresa Dunn” spends nights looking for companionship at the city’s singles bars. Goodbar is, in some ways, a flâneuse novel, with wicked portraits of the insecure, abusive men who pass through Dunn’s life. Rossner expertly captures the city’s nightlife, but from a woman’s perspective the scene takes on a deeply sinister tone; for all the supposed liberation of the era, sex could still bring about a kind of hell.

Lawrence Block, In the Midst of Death

It’s hard to think of a writer more emblematic of the city and the era than Lawrence Block, who started off in the 70s with gritty, vengeful stories from the city on the edge and is still cranking them out some 40 years later. 1976 saw the launch of Block’s Matt Scudder series. Scudder is an NYPD washout, haunted by drink and past sins. He lives in a Manhattan flophouse and spends his days at Armstrong’s Bar, flipping through the papers covering the latest atrocities. Occasionally, somebody plucks Scudder’s heartstrings and he springs into (unlicensed) action. In the Midst of Death is Block’s take on the Serpico-era efforts to clean up the force, with a back-alley Madonna thrown in to appeal to Scudder’s particular brand of chivalry.

Lawrence Block, The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling

Bernie Rhodenbarr, the hero of Block’s other big series launched in the 70s, is in many ways Matt Scudder’s opposite—a cat burglar with a literary sensibility and a come-what-may attitude toward life. After a few nighttime misadventures, Rhodenbarr decides to give himself a day job, opening up Barnegat Books in the Village. The store gives him ample excuse to chat literature, and it gives Block a reason to send his hero across the peripheries of the downtown art and letters scene. But used books just don’t pay the bills, so of course Bernie is back to his old habits soon enough. In The Burglar Who Liked to Quote Kipling, it’s a Maltese Falcon setup: a precious antique, a hired hand, and a hero who refuses to be the fall guy.

Chester Himes, Blind Man with a Pistol

Himes’ Harlem Cycle series actually wrapped with this novel in 1969, but at the end of the run, the issues simmering uptown were the same that would come to define the following decade: income inequality, the spread of hard drugs, a counterculture gone sour, sexual violence, and storefront religion taking hold in the city’s poorest neighborhoods. In Blind Man with a Pistol, Himes’ iconic detectives, Coffin Ed Johnson and Grave Digger Jones, are looking into the death of a white movie producer caught in a nasty situation in Harlem. The investigation takes them across the city, which is the real main character here: a dark, twisted vision of where things are, and where they’re headed. (It’s worth noting that during this period, Himes had already left New York and the US was living in self-imposed exile in Europe.)

John Godey, The Taking of Pelham 1 2 3

For most, the 1974 movie is what comes to mind first, but the novel, written by Morton Freedgood under his Godey pseudonym, was a hit in its own right. The story, set underneath New York, in the dreaded MTA tunnels, mainlined the city’s anxieties of the era: terrorists, hijackings, stalled trains, public apathy. Supposedly the story struck such a nerve that to this day MTA dispatchers do their best to avoid scheduling any 6 trains departing Pelham at 1:23 pm. (Trains are assigned a call number based on their departure time—hence the name of the downtown 6 train.)

Donald E. Westlake, Cops and Robbers

Westlake’s Cops and Robbers offers up a vision of beat cop corruption taken to the extreme: Tom and Joe are miserable flatfoots who drive in from Long Island every day to have another piece of their souls chipped away. They hate the job and the city, and eventually, what shred of integrity they had left disappears. One day, Joe finds himself, in uniform, robbing a liquor store. The trick works and his pockets are lined. Soon, the two partners team up with the mob and plan a heist of bearer bonds from a Wall Street operation. This is New York City at its most craven—the city’s guardians turning against the place they’re sworn to protect. Plus a look at the toxic city-suburbs dynamic of the 1970s, in the era of white flight and isolationism. (For companion viewing, check out the documentary, The Seven Five, now on Netflix.)

Don DeLillo, Great Jones Street

While not technically a crime novel, DeLillo’s third book taps into the same current of urban sleaze and a head-shaking wonder at how quickly and how extremely the 60s went to seed. The titular street isn’t today’s glitzy address or even the Great Jones Street of the art scene that would flourish in galleries and dive bars as the decade wore on. This was a Great Jones still connected to the old Bowery culture—a place for outcasts and washouts willing the days by and waiting on death. Bucky Wunderlick is a famous rocker living in a downtown flop. The money managers and record labels are banging on his door, while the streets are abuzz over a new drug that’s going to sweep the culture away. This isn’t DeLillo at his best, by any means, but it’s a powerful and deranged portrait of the start of something new for the city.

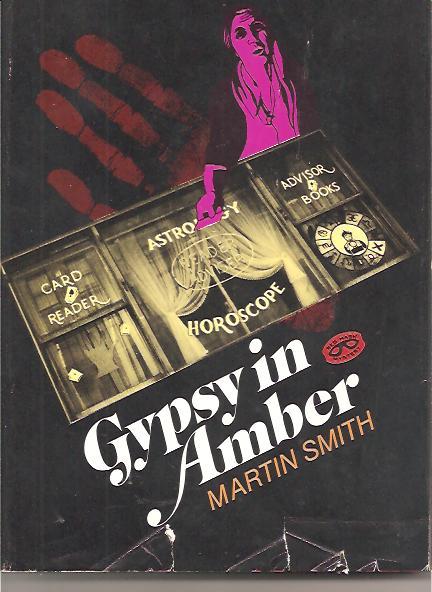

Martin Cruz Smith, Gypsy in Amber

Martin Cruz Smith would later rise to fame with Gorky Park and his Arkady Renko series, but in the 70s, he was just starting out in the mystery world with Gypsy in Amber. Romano Grey is a New York-based antiques expert and an occasional consultant for law enforcement in need of esoteric advice. He’s also a prominent member of the city’s gypsy population. In Gypsy in Amber, an antiques delivery goes awry, bodies begin to drop, and Grey is forced to navigate his peoples’ complex, cloistered world to get at the truth and to keep the gaja (non-gypsy) forces from putting an innocent man in prison. This is a slice of the city you probably won’t find anywhere else.

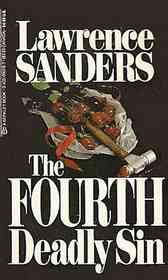

Lawrence Sanders, The Edward X. Delaney / Deadly Sin series

Sanders struck it big in 1971 with The Anderson Tapes, a bestselling thriller built out of fictional police reports and surveillance transcripts telling the story of “Duke” Anderson, recently released from Sing Sing and looking to make a score with a divorcee at a luxury high-rise on the Upper East Side. That book introduced Edward “Iron Balls” Delaney, the hard-nosed detective Sanders would stick with through the rest of the decade (and four more novels). The early books take a weary look at New York as a city full of hustlers, marks, and cops. Delaney eventually leaves the force, but these books are at their best as procedurals taking a close look at the police work. The Anderson Tapes, especially, taps into the coming decade’s sense of paranoia and its obsession with surveillance and the ever-present, corrupt state.

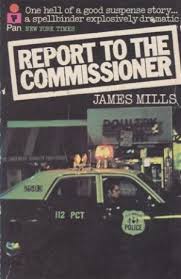

James Mills, Report to the Commissioner

Another novel built in part on documents—interoffice memos, reports, transcripts. This one follows the story of Bo Lockley, who, with his left-leaning views and sensitive outlook, is an unlikely recruit to the NYPD. In an attempt to prove his mettle, Lockley crashes an undercover operation targeting a Times Square pimp. Lockley’s vision of the city is ambivalent, the same as his feelings toward police work. It’s one more wrinkle in the troubled story of the NYPD in a difficult decade.