IN DECEMBER 1983, WHEN THE COCAINE era was in full ascent, the movie Scarface was released in theaters around the United States. At the time, the organization of Falcon and Magluta was annually bringing in roughly $100 million. To celebrate their success, the core members of the organization, along with their wives and girlfriends, every year traveled from Miami to Las Vegas for a week of gambling, floor shows, and a massive New Year’s Eve party at Caesers Palace Hotel and Casino.

One afternoon in late December, Falcon and eight members of his group went to see Scarface. The making of the movie had touched off a controversy in their hometown of Miami, where it was felt that the depiction of Cuban exiles as narcos was slanderous. Willy Falcon, following the lead of more formal exile organizations like the Cuban American National Foundation (CANF), forbid any of his gang from taking part in the production. Consequently, the movie was shot primarily in Los Angeles, using that city as a stand-in for Miami.

That afternoon in the Las Vegas movie theater, Falcon and his group found Scarface to be highly entertaining. They hooted and hollered during the outlandish depictions of cocaine violence and mayhem. They laughed at Al Pacino’s thick Marielito accent. The movie was so cartoonish in its attempts to dramatize the cocaine business—but with enough verisimilitude that the Boys were able to identify with it—that they were even flattered. They didn’t take it seriously. They thought it was a joke. But they could see that their lives were being elevated into the zeitgeist, and the movie offered the possibility of a kind of cinematic immortality.

Later came Miami Vice, another popular depiction of the city’s narco universe. Produced by the NBC network, the show debuted in 1984 and ran for five seasons. Along with the crime stories revolving around the cocaine underworld, the show was highly attuned to surface pleasures of Miami: the pastel colors, Armani suits, sleek powerboats that were right out of the Willy and Sal story, and popular rock, R&B, and Latin music. Miami Vice defined cool in the 1980s and suggested that it was all an extension of the city’s illicit cocaine universe.

Part of what made these works of popular entertainment so influential was that they appeared to be straight from the headlines. Movies depicting Prohibition had been popular, but they came years and even decades after the era they were depicting. Scarface and Miami Vice portrayed a phenomenon in real time, as it was happening, making those who were caught up in it feel as though they were living a dream.

In the decades that followed came many more movies and television dramas that used the cocaine universe for their storylines. Many took their cues from Scarface. Colombian, Cuban, and later Mexican narcos were invariably depicted as sociopaths or flat-out psychopaths in a business that politicians and people in law enforcement characterized as “evil.” If there was to be a presentation of the cocaine business in entertainment or even in real life—through reports on the television news—it was invariably steeped in violence.

“Say hello to my little friend,” Tony Montana’s business motto in Scarface, was a prelude to violent mythmaking, and that seemed to be the way the American public was primed to receive any and all stories related to the cocaine business.

As is usually the case, the reality was more complicated.

For most of its existence, Willy Falcon and Los Muchachos’ operations in the cocaine world involved little violence. The Boys did not seek to eliminate rivals through murder and intimidation. They did not punish their members internally with torture or killing or even the threat of killing. They did not pull out chain saws, à la Scarface. They did not mow down hordes of partygoers with Uzi submachine guns.

It was true that the world in which they were operating was a violent one. The narcosphere, as it was sometimes called, involved violence from top to bottom. Lowly street dealers used violence, and so did Pablo Escobar, believed in the 1980s to be the Godfather of the business. And yet, the example of Los Muchachos suggests that it was possible to succeed at a high level without a reputation for murder—especially if your forte was importation and distribution, not dog-eat-dog entrepreneurship at the retail level. (1)

The story of Los Muchachos shows that it was not violence that was the dominant characteristic of the cocaine business.

It was corruption.

Dirty cops, agents, lawyers, judges, and politicians feeding off the profits of the narcosphere is what made the world go round. This existed at every level of the business, in every country, state, and city where kilos of coke passed through grubby hands on its way to and up the nostrils of the consumer. Falcon and Magluta played this game. With what seemed like unlimited resources, they bought off representatives of the system, from a county sheriff who made it possible for them to land their product at a clandestine airstrip, to a high-level money launderer who became the president of a country.

Corruption represents a human failing. It is usually practiced by people who, out of need, convenience, or necessity, choose to violate the principles by which they claim to live their life. When it comes to corruption, greed is the most obvious culprit, stemming from a celebration of wealth, avarice, and the accumulation of more and more and more. Sometimes a person takes illegal payoffs to pay for a friend’s or relative’s medical costs, to deal with a family crisis, to put a kid through college. Whatever the reason, corruption as a shortcut to the American dream became an operating principle that would turn the cocaine business of the 1980s into the most lucrative illegal endeavor on the planet.

THE NARCOSPHERE IS NOT A physical place; it is a realm of operation, and a state of mind. It spans sovereign boundaries, physical space, borders, and political jurisdictions. Bolivia and Peru, where the coca plant is grown and cultivated, are parts of the narcosphere, as is Colombia, where the plant is processed into cocaine hydrocholoride. For a long time, Panama City served as the central money-laundering domain of the narcosphere. The Caribbean islands, and later Mexico—which would become the preeminent region of transshipment—have been and are corridors of the narcosphere. The United States of America, the primary marketplace for the product, with more users of cocaine than anywhere else in the world, is arguably the engine that runs the entire operation. Regional players—narcos, cokeheads, drug mules, people in law enforcement, judges, politicians, distributers, dealers, citizens who look the other way—are all participants in this field of illegal commerce that still thrives in the present day.

For more than a decade, Falcon and his partners not only operated within this world but also succeeded at it to a degree that was unprecedented.

In the years since this story was in the headlines, some would rather minimize and diminish its significance to the point where one of the prosecutors of Willy and Sal, in an interview for this book, made the statement, “Falcon and Magluta were probably the most successful and biggest drug dealers in South Florida, but they weren’t into importing drugs. They were receiving the drugs from smuggling gangs, and then they would distribute it, but they weren’t im- porting.”

This is a breathtakingly erroneous statement from someone who prosecuted Los Muchachos. As you will see from reading this book, Willy and Sal brokered major importation deals from around the narcosphere. In lore and legend, they have been portrayed as Cuban American playboys, high school dropouts, and amateurs who stumbled onto a hot property and exploited its popularity throughout the Dionysian era of the 1980s.

There is much more to this story than has been previously known. Partly, this is because Falcon and his closest associates have never talked about or been interviewed on the subject—until now. Back in the day, when they were facing prosecution, it was not in their interest to talk openly and honestly for the record. But the passage of time has a way of rearranging priorities. Most of these people have paid their debt to society, in many cases with long prison sentences. Over the decades, Falcon and his former partners have read accounts in the press or online, or seen documentaries on television and the internet, that present a dubious version of their personal histories. Falcon, for one, has waited a long time to give his version of what happened. His willingness to do so opened the door for many others from Los Muchachos to come forward and cooperate with the writing of this book. They represent a generation of people—mostly Cuban-born or Cuban American—who got caught up in this wild era, have paid the price, and now live with the memories of their involvement in the golden age of cocaine.

It is time that this story be told from the point of view of those who lived it. Certainly, from a historical perspective, these events are significant to an understanding of the American process during a time of unprecedented crime and mayhem. But it is also important to understand that many lives, on both sides of the law, became enmeshed in the events of this time, and that their experiences—which became fodder for criminal indictments and media accounts—deserve to be recounted, preserved and acknowledged on a human level.

History is not simply a cavalcade of big events—wars, elections, or public policies that shape the flow of human endeavor. It is also a consequence of simple people making choices—good, bad, or indifferent—that lead them on a life-altering journey, a singular adventure that maybe shapes the times in which they live. In the case of those who composed Los Muchachos, the passage of time has shed new light on troubling personal events, unearthed deeply buried emotions, rattled the cages of ghosts, and flung open the doors of repressed recollections from long ago.

___________________________________

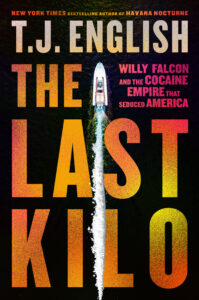

From the book THE LAST KILO: Willy Falcon and the Cocaine Empire that Seduced America by T.J. English. = Copyright © 2024 by T.J. English. To be published on December 3, 2024 by William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

(1) After Falcon, Magluta, and eight others from their group were indicted in 1991, there were killings. There were four murders and two attempted murders of potential witnesses against Los Muchachos. It was widely speculated that these killings were related to the case of Los Muchachos, but there was never any evidence linking Falcon to any of these murders, and he was never charged. Magluta was later charged and found not guilty on all murder counts.