Ask any woman who writes fiction meant to shock or disturb about response to her work, and she will no doubt offer up at least one anecdote involving something like, “You write that? But you look so nice!” It’s certainly commonplace among modern female horror writers, and it seems likely that their sisters in the past occasionally endured similar responses. It’s hard to say exactly what readers imagine a female horror writer looks like.

Women have been writing this sort of fiction more than even the most avid of readers may realize and for just as long—perhaps longer—than their male counterparts. Why aren’t they as well-known today as their male contemporaries? Why did so many feel compelled to write under gender-neutral names or as “Mrs. XXX”? Some of them did achieve literary recognition—this book, for example, contains work by Edith Wharton, Harriet Beecher Stowe, George Eliot, and Zora Neale Hurston, writers certainly as highly regarded as any of their male peers; however, none of them are thought of primarily as writers of supernatural fiction, nor were their reputations enhanced by their horror credits. Those whose stories tended to center on more arcane themes—women like Mrs. Oliphant, Vernon Lee, or (arguably, given that she wrote in a number of genres but her best work was horror) Mary Elizabeth Braddon—are now less studied and anthologized than, say, Ambrose Bierce or M. R. James. Rhoda Broughton was a popular author during her lifetime (whose sharp tongue was said to have intimidated Oscar Wilde), but she’s now far less known than her uncle Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu.

Why should that be? It seems too easy to simply cite sexism (although there’s certainly more than a grain of truth in that as well). Perhaps they didn’t fit readers’ preconceived notions of what they should be.

Or maybe there’s something subtler at work. Did they write about subjects or themes that were different from what men were writing about? Some did. Many of these women were deeply involved in social movements of their time—they were suffragettes, anti-vivisectionists, and labor advocates—and their work often involves contemporary issues that may seem unimportant to modern writers. Nineteenth-century tales of matrons fretting over parenthood or wrangling with their nursemaids or wives living in terror of being widowed may be harder for a reader in the twenty first-century to relate to than, say, concerns about the appropriate bounds of science or the end of the world (themes that fascinated Mary Shelley, among others). Like many writers of the nineteenth century, these authors refused to be pigeonholed, confined to a “genre” (genres themselves probably being a twentieth-century invention); instead, they wrote stories about things that moved them, be the stories romantic or scary or mystifying. Today, we may look back and say “Mary Elizabeth Braddon wrote crime fiction” or “Louisa May Alcott wrote young-adult fiction.” To a one, they would have rejected such classification—they wrote stories. And for many of these women, they wrote because it was their only possible livelihood, their only means to support a dependent family.

A good story doesn’t have an expiration date. It’s a snapshot of history, and if it’s an accurate depiction, it reveals our past and reminds us of those elements that have endured into the present. Rhoda Broughton’s “The Man With the Nose,” for example, may at first seem to be (to put it mildly) old-fashioned, what with its plot revolving around a helpless wife and mesmerism, but it also captures the terror of being stalked by a stranger, a form of dread shared by people across the centuries. May Sinclair’s “Where Their Fire is Not Quenched” and Edith Wharton’s “The Fulness of Life” both capture the disappointments that many still experience when their relationships don’t live up to their expectations. Zora Neale Hurston’s “Spunk” shows a woman both wowed and cowed by a powerful man whose dangerously toxic masculinity will be instantly recognizable to readers from any age. And who doesn’t feel some of the anguish of the mothers at the hearts of Josephine Daskam Bacon’s “The Children” or Mrs. S. C. Hall’s “The Drowned Fisherman”? Religion is brought into play in several of these stories, proving almost invariably ineffective against greater forces—for example, in Vernon Lee’s “Marsyas in Flanders,” Florence Marryat’s “Little White Souls,” and Alice Brown’s “The Tryst,” ancient mythology seems more powerful than modern Christianity. If the nineteenth-century was rushing forward at dizzying speeds that left many of those living through it consumed by existential fear and anxiety, surely our modern world isn’t immune to those concerns.

Not all of these stories are about subjects that are traditionally “female.” Some, like Mary Cholmondeley’s terrifying “Let Loose,” exist simply to entertain the reader with a roller coaster ride that leaves us turning the pages ever faster; others, like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “The Ghost in the Mill” or Gertrude Atherton’s “The Dead and the Countess,” offer gentler, more playful takes on folklore. Their charm is impossible to ignore even a century-and-a-half later.

It must also be admitted that parts of these stories may be difficult for modern readers to swallow. The narrators of the tales may be casually cruel to servants, people of different races or faiths; colonialism might rear its ugly head; and of course misogyny is on open display. A failure to be reflective of twenty-first century attitudes, however, should not be cause to consign a story to obscurity. If we are to change how we treat others, if we are to progress, we must look unblinkingly at our past and acknowledge our mistakes and wrong-headed attitudes. A gifted writer is one who can show us who we were, no matter how much we may deplore our own behaviors.

This anthology is not intended to serve as a memorial to forgotten women writers or to somehow apologize to them for their marginalization. It’s not meant to be a history lesson about the birth and growth of supernatural fiction. Instead, it’s meant to present to a modern audience important works by important writers—works that have been left too long in the shadows, with timeless insights into human nature and our basic fears. In a world where the voices of women continue to be ignored, we hope that readers will rejoice in rediscovering these echoes from the past two centuries, with messages that are as critical today as when penned.

___________________________________

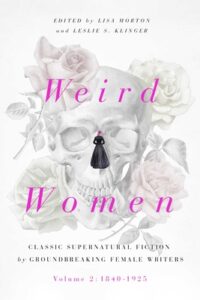

Excerpted from the Introduction to Weird Women, Volume 2: 1840-1925: Classic Supernatural Fiction by Groundbreaking Female Writers, edited by Lisa Morton and Leslie S. Klinger. Copyright 2021, Lisa Morton and Leslie S. Klinger. Published by Pegasus Books. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.