Last month, San Francisco’s distinguished Castro Theater provided the setting for a birthday party of sorts. The Long Goodbye, a 1973 neo-noir thriller, based on the 1953 novel by celebrated pulp scribe Raymond Chandler, was about to turn fifty. The guest of honor, star Elliott Gould, preceded the screening with fun and happily meandering reminiscences about the film and his exceptional career. Besides being the sort of occasion that made you grateful for a return to inhabiting other people’s physical presence, the screening highlighted what a valuable and challenging contribution to popular culture this film has always been.

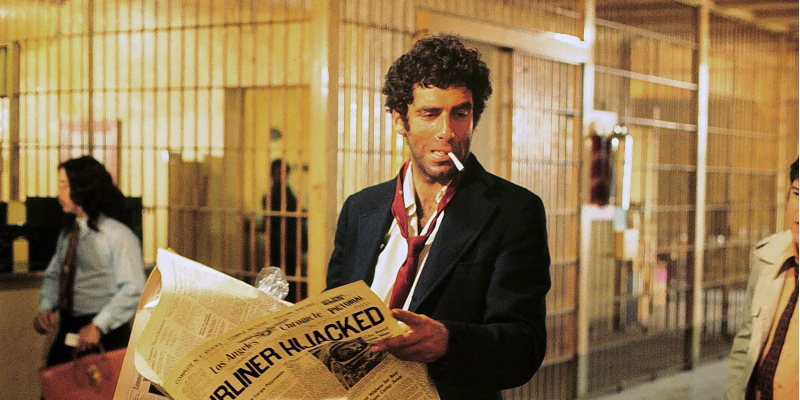

In The Long Goodbye, Gould plays Philip Marlowe, a perpetually down-on-his-luck private investigator holding his life together with loose thread. When his old friend Terry Lennox (ably portrayed by former baseball player Jim Bouton) turns up late one night asking for a ride to Tijuana, Marlowe reluctantly performs the good deed for which he’ll spend the balance of the movie getting punished. That punishment includes, but is not limited to, a battle of wills at a creepy clinic, near dismemberment by a truly unhinged mobster (Mark Rydell), a brush with an alcoholic literary giant clearly modeled on Ernest Hemingway (Sterling Hayden, never better), and a dalliance with a deceptively fatal femme (Nina Van Pallandt).

As a character, Philip Marlowe has led an interesting life. Born on pulp paper in the thirties, he has since graduated to the wispy scritta paper of literary anthologies, a newish neighbor of such cultural old money as Ahab and Huck Finn. Long before gaining ground with literary critics, he was a film star, having been immortalized onscreen by Humphrey Bogart in 1946’s The Big Sleep. This is the Marlowe that most of us have met, if perhaps inadvertently: the grim, fast-talking, tough-as-nails navigator of labyrinthine corruption and lies. While Bogart’s performance is as fully realized a contribution to world cinema as any that American film can boast, it is also a partial rendering of the rather strange character that Chandler created. We never doubt the toughness of the literary Philip Marlowe, and yet he spends a not inconsiderable portion of each book getting the innermost stuffing knocked out of him. Gould, whether to recuperate lost facets of the original character, to escape Bogart’s imposing shadow, or with some other motivation front of mind, gives us Marlowe the chatty punk. Fists naturally find this man. In the contact sport of hard-boiled detection, he’ll take a hit to make a play. If he gets the last word, he probably speaks it under his breath. He can’t even find his cat.

This kind of shift was surely necessary in 1973, as Watergate came to light and the war in Vietnam drew itself to a bloodcurdling close. An idealist, even one as sharp-eyed as any Bogart character, could not have seen a hand in front of his face. The genius of Gould’s performance was to take the hard-boiled, trench-coated private detective, that wartime symbol of wised-up American manhood, and infuse him with a different and more volatile kind of wisdom, the kind that had been recently modeled by the disaffected drifters at the center of so much “New Hollywood” fare. This is a vision of the private eye that likely could not exist until after Dennis Hopper’s performance in Easy Rider (1969), or Jack Nicholson’s in Five Easy Pieces (1970). Gould’s Marlowe, unlike Bogart’s, is never permitted the fantasy that he can outsmart the entire system. Even when he asserts some inalienable value of human life, he can do it only by killing, something he does not do in the novel. During the early seventies, this must have seemed apposite in ways I can only imagine.

And yet, watching The Long Goodbye in that grand old theater last month, I was struck by how powerfully it speaks to our time as well. It does this mostly by mouthing questions about masculinity (which ranges in this film from toxic to radioactive), networks of political and corporate corruption, celebrity culture, the contemporary obsession with wellness, and the evergreen problem of holding rich people accountable for their actions. A clinic run by the manipulative moneygrubber Dr. Verringer (Henry Gibson), where treatment consists of isolating, doping, and de-moneying the rich, offers a commentary on the business of health that doesn’t seem past its expiration date in our own wellness-obsessed cultural moment.

Altman’s cinematic output is famously uneven. His highs could scarcely be higher: M.A.S.H., Nashville, McCabe and Miss Miller. Among his lows are dreamy misfires like Brewster McCloud, flawed romps like Popeye, and a large assortment of television commercials and other ephemera. At his best, Altman captures the battered humanity of characters with nothing to survive on but their own overweening cleverness. They often show a face to the world whose tongue is firmly in cheek, whose eyes seem almost frozen in a sideways glance, leaving them blind to the danger ahead. Marlowe is a prime example. Among his first mumbled lines in the film is “It’s okay with me,” and he meets the escalating violence and intrigue of the plot with a salvo of okays. Only in the film’s final scene, when Lennox’s actual fate is revealed, does he reach his breaking point. Gould said it best at the screening: for this Marlowe, everything is okay until it’s not.

As I can never resist mentioning to any listener half-interested or better, The Long Goodbye is also notable for granting us a glimpse of a star in its infancy. Among the leg-breakers flanking mobster Marty Augustine in one particularly fraught scene is a ludicrously broad-shouldered and muscled young man who, on closer inspection, turns out to be a very young Arnold Schwarzenegger. At one point he cracks his knuckles loudly enough that his role should have been accorded speaking status thereafter. Asked what it felt like to share the screen with the future governor of California, Gould neither hesitated nor missed: “It didn’t feel like anything.” He added that Schwarzenegger has always been kind to him, though few of the friendships across his long and remarkable career have rivaled those with Altman and Alfred Hitchcock. (Taylor Swift, it may as well be reported here, knew him from his role on Friends, as does much of her generation.)

To hear Gould recount The Long Goodbye’s wandering, at times improbable backstory was to recognize that masterpieces, like people, live their lives forward, at the mercy of choices and circumstances and contingency, with absolutely no guarantee of turning out for the best. Not until 2021 was The Long Goodbye accepted into the United States National Film Registry, thus marked by the Library of Congress as “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” It should continue to be viewed for as long as we remain concerned with the nature of vice and the constant, often dispiriting struggle for truth.