A lot of people believe that Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood established the true crime genre in 1966. This is what’s known, in purely technical terms, as bullshit. Capote’s account of the Clutter family killings made true crime writing respectable to cultural gatekeepers and highminded prudes, but readers have been gobbling up stories of human criminality for approximately as long as we’ve been able to speak.

My new book, The Southern Book Club’s Guide to Slaying Vampires, revolves around a book club that reads true crime, leavened with the occasional thriller, who decide their new neighbor is probably a vampire and needs to be destroyed. I’ve always considered true crime sort of seedy, avoiding the cheap mass market paperbacks, with their inevitable 8 pages of grimy photos, like the plague, but that’s because I was a jerk. Doing my research introduced me to a wild n’wooly, democratic, rough and tumble, blood and guts genre that stretched all the way back to Cain and Abel, and I’d been missing out on all the fun.

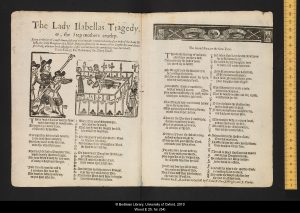

PAMPHLETS & SONGS (15th – 17th century)

Gutenberg invented the printing press and about five minutes later they started grinding out pamphlets recounting that week’s most gruesome murders. With titles like “A true and most horrifying account of how a woman tyrannically murdered her four children and also killed herself, at Weidenhausen near Eschwege in Hesse,” sung to the tune of popular hymns like “Come Unto Me, Says the Sons of God,” their writers adopted tones of headshaking bewilderment at the state of this fallen world, (“My dearest reader, this is, unfortuantely, may God have mercy, one piece of horrifying news after another,”) before launching into vivid verses:

“She first went for the eldest son

Attempting to cut off his head;

He quickly to the window sped

To try if he could creep outside;

By the leg she pulled him back inside

And threw him down onto the ground;

…

O please don’t kill me! Spare me, do!

But no plea helped, it was in vain;

The Devil did her will maintain.

She struck him with the self-same dread

As if it were a cabbage head.”

A catalogue of all the ways other people’s families are so much worse than yours—with dads murdering kids, and kids murdering mom—they came illustrated with helpful woodcuts. One 1573 murder inspired two pamphlets featuring helpful diagrams showing exactly how the victim’s body had been dissected.

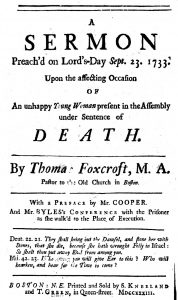

AMERICAN EXECUTION SERMONS (17th – 18th century)

In colonial America, some days were extra special. Those were the days when a sodomite, murderer, bad parent, or burglar was led in chains before the church and a celebrity minister preached an execution sermon before that wicked child of God got the rope. Crowds of up to 5,000 people traveled dozens of miles (which was a long way back then) to hear the minister weave great clouds of Biblical wrath over the heads of some poor sap before they were led away “with all convenient haste” to meet their maker for stealing grapes, or picking pockets, or killing their baby. These flowery sermons were printed and distributed so even if the trip was too far you could still wallow in every odious detail of your neighbor’s sinful life that had finally led them straight to Hell.

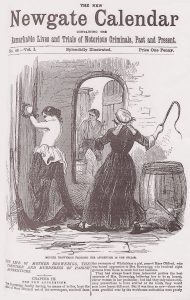

NEWGATE CALENDAR (18th – 19th century)

Originally a simple calendar of executions kept by Newgate Prison, eventually The Newgate Calendar: Or, Malefactors’ Bloody Register became the most widely read book in England for about a century. (The American equivalent was The Record of Crimes in the United States. Nathaniel Hawthorne was a big fan.) Noted ravishers of women, like the aptly named James Booty, had their lives spun off into solo pamphlets, but the regular calendar still featured a cavalcade of champions: William Duell, hung until dead for rape and murder, taken to have his corpse dissected by medical students, only to spring back to life. Embarrassed, the court commuted his capital sentence to exile in North America. Alexander Balfour, obsessed with his sister’s tutor, informed her that if she ever got married he’d murder her husband. Then she got married and he murdered her husband. Scheduled for a beheading, he escaped, disguised as his sister, and died of natural causes 50 years later. The Calendar sported a wry turn of phrase that seemed to presage the moral tone of EC Comics in the Fifties, “Arthur Chambers, A Master of Thieves’ Slang, who was full of Artful Tricks, which, however, did not save him from the Gallows at Tyburn, where he found himself in 1706” read one entry.

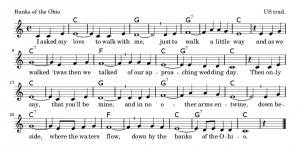

MURDER BALLADS (18th – 20th century)

Like the poems and songs in 15th century pamphlets, only with better tunes, murder ballads became a uniquely American form of true crime tale, often relating the story of a young woman murdered for getting pregnant, or falling in love, or just plain old hanging out with the wrong people. Songs about the 1808 murder of Naomi Wise in North Carolina have outlasted anything we might know about the real Naomi, and the beheading of the pregnant Pearl Bryan in 1896 spawned three distinct ballads, none of which mention the fact that she probably died of a botched abortion performed by her dental student boyfriend who sawed off her head in a failed attempt to prevent her identification. In the Thirties and Forties, female singers transformed themselves into more than victims with tunes like Patsy Montana’s “I Didn’t Know the Gun Was Loaded” but even back in the 1860’s there were still some tough broads in these ballads, like the notorious poisoner, Lydia Sherman:

“Lydia Sherman is plagued with rats

Lydia has no faith in cats.

So Lydia buys some arsenic,

And then her husband gets sick;

And then her husband, he does die,

And Lydia’s neighbors wonder why.”

GANG BUSTERS (1936 – 1957)

For 20 years, working class Americans religiously tuned into Gang Busters, a radio show about real life criminals based on interviews with their victims, witnesses, and the men who put them behind bars. Actor Phillips Lord had achieved national fame playing the folksy backwoods philosopher, Seth Parker, before producing this true crime show as a public service. Unfortunately, he reached out to the head of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover, for assistance and Hoover’s suffocating sanctimony almost sunk the first season. Lord kicked the stuffed shirt G-Man off the show for the second and insisted on more: more gunshots, more sound effects, more blood, more action, more excitement, and more crime. Most of his audience earned less than $3,000/year, rich people ignored it when not writing editorials about how it encouraged crime, and kids gobbled it up as Palmolive Shave Cream and Palmolive Brushless Shave Cream — the shave creams made with olive oil — presented bloody shoot-outs with Bonnie and Clyde and let viewers know, in the words of one 12 year old boy, “what bandits are like.” Capturing the populist anger at banks and the forces of law and order with its romantic audio portraits of the renegades who bucked the system, the show’s opening was so loud, lurid, and exciting that to this day when someone says something “comes on like gangbusters” they’re referring to a radio show that went off the air before they were even born.

TRUE DETECTIVE MAGAZINE (1924 – 1995)

Printed on the grittiest pulp and laid out with all the aesthetic appeal of a bodybag, True Detective rocketed to popularity in the Thirties, selling two million copies per month for its first 20 years. Founded by the intense, muscular vegetarian, Bernarr MacFadden, the magazine was an intense, muscular carnival barker for American crime: “Weird Case of the Rapist Who Wanted Romance!” “Brooklyn’s Vicious Thrill-Kill Kids!” “What Powerful Lure Drew Him From Ogling Nude Dancers to his Brutal Slaying?” “Corpse at the Picnic!” “House Full of Skulls!” As reputable as a freakshow, its defenders cling to its handful of respectable accomplishments like fig leaves: the 1931 series, “I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang,” exposed the brutality of convict labor in Georgia, and it published work by pulp stylists, Jim Thompson and Dashiell Hammett. But really, its greatest accomplishment was spawning an avalanche of detective magazines, scare sheets, and supermarket tabloids for decades to come.

IN COLD BLOOD & THE EXECUTIONER’S SONG (1966 & 1979)

When people try to justify true crime, these are the books they cite. Capote’s account of the Klutter family killings launched a cottage industry of movies, books, more movies, and even more books, but still stands as a great read. Mailer’s account of Gary Gilmore’s decision not to oppose his death sentence for the murder of two men in two separate robberies won a Pulitzer but is longwinded and exhausting, like Mailer himself. For the literati, these books invented true crime because the “right” kind of writers were finally tackling it —rich, white men who read the right magazines—totally ignoring the fact that the “wrong” kind of writers (female, non-white) had been doing the same thing for decades, like Celia Thaxter in 1875, Edna Ferber in 1935, and Zora Neale Hurston in 1956.

ANN RULE’S A STRANGER BESIDE ME (1980)

Ann Rule was a harried single mom trying to support four kids on the money she made freelancing for True Detective under the name “Andy Stack” when she landed her very first book contract. Hired to write a quickie about the so-called “Co-ed Murders” in the Pacific Northwest, Rule didn’t have a clue these would become some of the most famous serial killings in modern history, nor that they were being committed by Ted Bundy, a good friend who worked next to her at a suicide hotline. Rule would go on to write numerous true crime paperbacks, but none rival the queasy intimacy of her first. The Stranger Beside Me established the template for the contemporary true crime genre, but Rule warped it into an uncomfortable blend of forensic analysis and autobiography. Forget the cold, clinical, God’s eye view of In Cold Blood. If you want to read the sweaty, disquieting, elegiac masterpiece of the genre, no book does it better than Stranger.