Secrets are the elemental stuff of drama. Poets, playwrights, and novelists have used them like a churning engine through the ages to keep readers transfixed with the central challenge, which is always—will private matters be kept private? But then someone applied encoding and decoding to the formula, which acted like a third rail that propelled the engine to run faster and farther. It’s a neat trick. When the secret of the plot is further concealed within a cryptographic message then—voilà—the overall dramatic element is profoundly magnified.

Take for example the most infamous trio of numbers of all time: 666. It’s from The Book of Revelation, a mysterious and poetic Bible chapter, which is quite a page turner. As described in the third person voice, the triple-6 code variously stands for Babylon the Great, the Mother of all Prostitutes, and the total Abomination of the Earth.

Yikes!

But who really is this no-good 666 thing/being/monster coming our way? That is the big question. And the answer could be kind of important, particularly as many believe the arrival of Mr. 666 portends nothing less than the end of time. Thus, we have a dramatic secret, profoundly magnified by a mysterious code. Spoiler alert: I solve the 666 puzzle at the conclusion of this article (no peeking).

Flash forward a couple thousand years to the time when books, newspapers, and movies grasp the profitability of encoded secrets. This happened largely because of the two founding masters of the mystery genre: Edgar Allan Poe and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Each of them helped galvanize the trend in popular culture.

there’s another first for which Poe gets insufficient credit. He was the first to portray cryptography and codebreaking as central to the plot of his story The Gold Bug.

Poe, of course, is the author of Murders of the Rue Morgue, the first detective story, which earned him the title “Father of Detective Fiction.” Consequently, the annual awards presented by Mystery Writers of America are called “Edgars.” But there’s another first for which Poe gets insufficient credit. He was the first to portray cryptography and codebreaking as central to the plot of his story The Gold Bug.

In the early 1840s, while writing for a Philadelphia weekly, Poe challenged his readers to send him substitution cryptograms, boasting that he possessed the necessary skills to decode them. That was worrisome to some readers, in part, because of superstition. At the time, the act of decoding secrets seemed to mean possessing a magical, if not creepy talent. This may have been due to the Rosetta Stone. Discovered in 1799, it was not fully decoded until the 1820s. Being able to finally hear voices from ancient Egypt speak through their hieroglyphs was practically a celestial event for people of the early 19th Century.

Nonetheless, Poe’s readers were intrigued. They accepted his offer and the poet did indeed decipher many submissions from around the nation. The result was immediate and electric. Encoded puzzles suddenly became socially acceptable. They soon enjoyed wide popularity in magazines and newspapers, an affinity that continues to this day in the form of cryptic crosswords.

Seeing the surging demand, Poe capitalized on the trend with his short story, The Gold Bug. Like most Poe prose, it can be difficult for modern readers, but highly rewarding for anyone who wades in, and stays with it. Published in 1843, it details the story of three men who find a mysterious golden scarab and an encoded parchment that ultimately leads to the discovery of a great pirate’s treasure buried on the marshy coast near Charleston, S.C.

The encoded parchment reads:

53‡‡†305))6*;4826)4‡)4‡);806*;48†8¶60))85;1‡);:‡

*8†83(88)5*†;46(;88*96*?;8)*‡(;485);5*†2:*‡(;4956*

2(5*—4)8¶8*;4069285);)6†8)4‡‡;1(‡9;48081;8:8‡1;4

8†85;4)485†528806*81(‡9;48;(88;4(‡?34;48)4‡;161;:

188;‡?;

The decoding narrator explains his method thusly:

Of the character 8 there are 33.

; “ 26.

4 “ 19.

‡ ) “ 16.

* “ 13.

5 “ 12.

6 “ 11.

† 1 “ 8.

0 “ 6.

9 2 “ 5.

: 3 “ 4.

? “ 3.

¶ “ 2.

-. “ 1.

The explanation for Poe’s somewhat obscure explanation is: beginning with the top line, the parchment contains thirty-three number eights. The second line means there are twenty-six semi-colons in the message. The third line means it has nineteen number fours, etc.

He then goes on to explain that the letter “e,” which every modern Scrabble player knows, is the most common letter in the English language, followed in order by: a, o, i, d, h, n, r, s, t, u, y, c, f, g, l, m, w, b, k, p, q, x, z.

Therefore, in the puzzle, the number five is the letter “a.” The dagger (†) is the letter “d.” The number eight is the letter “e,” and so on.

Ready to solve the puzzle? It reads:

A good glass in the bishop’s hostel in the devil’s seat

twenty-one degrees and thirteen minutes northeast and by north

main branch seventh limb east side

shoot from the left eye of the death’s-head

a bee line from the tree through the shot fifty feet out.

Tah-dah!

Poe’s story was massively popular, winning top prize of $100 in a contest that was probably the largest chunk of money he ever earned as a writer in a single payment. It also went on to influence many writers.

And that’s a perfect segue to The Adventure of the Dancing Men by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, published in 1903. In it, a lady is being harassed by someone leaving a series of secret messages. Each of them look like the innocuous drawing of a child:

When I first read this story at the age of 13, I guessed the language was a type of semaphore language, such as when ships communicate silently with handheld flags. But it’s not. Holmes immediately recognized the drawings as symbol-for-letter substitution cryptograms and promptly set about solving the mystery using the same formula enumerated by Poe in The Gold Bug. He, too, started decoding with the knowledge that “e” is the most common letter in the English language.

Ten years later, in The Valley of Fear, Doyle utilized another coding technique known as a common book cipher. This is where both sender and receiver possess a copy of the same book, and most importantly, the same edition. Holmes receives an encoded message from none other than Professor Moriarty that reads:

534, C2, 13, 127, 36, 31, 4, 17, 21, 41 DOUGLAS, 109,

292, 5, 37, BIRLSTONE, 26, BIRLSTONE, 9, 47, 171.

With the highest number being 534, the detective figures, if it’s a common book cipher, then it must be a thick book, such as an almanac. A minute later, almanac in hand, he decides C2 stands for column two, and that the numbers represent words within that column.

And the message reads:

There is danger…may…come…very soon…one…Douglas… rich… country… now…at Birlstone…House…Birlstone…confidence… is… pressing.

***

Between Poe and Doyle, readers were hooked. They loved it. Ironically it took another 66 years before Ken Follett picked up on the passion with a blockbuster novel. He used a common book cipher in The Key to Rebecca, a WWII based international bestseller. Here, the secret cipher was found in Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca.

Jumping to recent history, some popular reads that cleverly utilize cryptology include: The Name of the Rose, by Umberto Eco; The Da Vinci Code, by Dan Brown (and pretty much all of his books); Cryptonomicon, by Neal Stephenson; Enigma, by Robert Harris; The Eleventh Hour, a children’s story by Graeme Base; and The Rule of Four, by Ian Caldwell and Dustin Thomason.

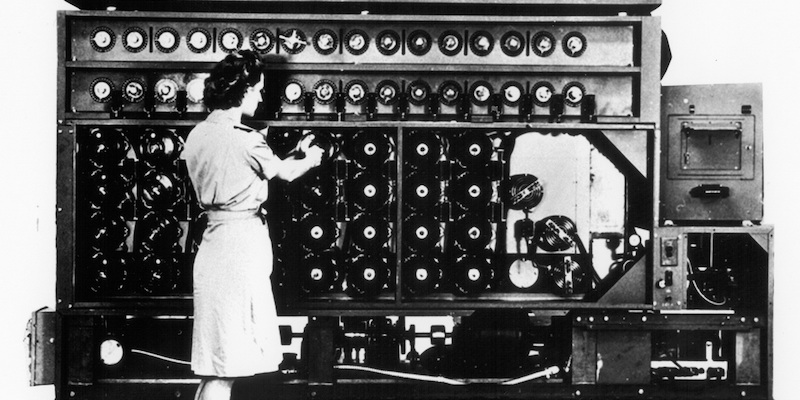

The short list of movies includes: The Imitation Game, National Treasure, Zodiac, Contact, and Sneakers. Personally, I loved The Imitation Game about the great Alan Turing’s decoding of the Nazi military code.

Like DNA’s double helix, there are two common strains encircling all of these stories. First, there is the formula of intensifying a secret with a code. And second, there is our collective inheritance bequeathed by the two masters of the mystery genre.

The same is true of my own novel, Flight of the Fox, (July 2018, Down & Out Books), where Sam Teagarden, an innocent math professor, flees black-ops hit men while decoding a mysterious file the FBI does not want to be made public. In Teagarden’s case, his decoding effort is first aided by a publicly available website called deepdecipher.com, and secondly by Xxxxx xxx xxxx (Blacked Out for Security Purposes).

Now, what about the Beast:

And I stood upon the sand of the sea, and saw a beast

rise up out of the sea, having seven heads and ten horns,

and upon his horns ten crowns, and upon his heads the

the name of blasphemy. (Revelation: 13.1)

Wow, this is one bad dude coming our way.

Fortunately, the ending of this story is already known, and it’s not at all catastrophic, at least, it’s not catastrophic for us or for our collective future. Using basic Internet research tools, we learn that Revelations was written in the late the First Century. The coded identity of the Beast would have been recognizable to readers of that era as a direct reference to the infamous and megalomaniacal Caesar Nero, who ruled Rome from 54 to the year of his death in 68 AD. He justifiably gets much blame for widespread torture, execution, and general harassment of everyone adhering to a new religion called Christianity.

Here’s how the code worked:

At the time, there was a semi-popular practice, somewhat occult, called Gematria, a system for encoding Hebrew letters as numbers. (Sound familiar?) When Neron Kaisar (Greek for Nero Caesar) is translated to Hebrew it becomes Nrwn Qsr. Using Gematria, the number value of those letters equal 666. Although, since The Book of Revelation was written in Greek, the original would have read: chi (600), xi (60), stigma (6).

Lastly, here’s my own relatively simple coded message, concocted for readers to try on their own:

8 @ % * 7 ! 8 & < $ @ > ^ ! & + 8 = ~ * ! $ 8 =

Should you have any difficulty, remember the lessons taught by the man who died under mysterious circumstances at the young age of 40 in the city of Baltimore. Should you still have difficulty, or seek confirmation of your answer, go to deepdecipher.com, which will secretly redirect you to another website, where the solution awaits.