As a child of the 1970s I was surrounded by pulp heroes that included my beloved James Bond films, Batman reruns and The Shadow comic books drawn by Michael Kaluta, but it wasn’t until the release of the Weird Heroes paperback series, which was subtitled “New American Pulp,” that I first saw the word “pulp” in print. Edited by Byron Preiss, the eight WH books were split between anthologies and stand-alone novels written by Philip José Farmer, Ted White, Ron Goulart and others. Further research guided me towards an array of yesteryear radio shows, comic books, novels, short stories and movie serials that highlighted the action packed adventures of Buck Rogers, The Green Hornet, Lone Ranger, Dick Tracy and numerous others now forgotten character that provided cliffhanging entertainment for generations.

The true meaning and application of the word “pulp” has been argued over by purists, especially after Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 classic Pulp Fiction brought the word out of the shadows of another era. For some, “pulp” represents the era when men’s adventure magazines were printed on that type of paper, while for others the word signifies action heroes on earth, in space and on various sides of the law. For others, “pulp” is more about the style of the writing.

“For me, Pulp is plot based, yet the characters are exciting and fleshed out in an over the top sort of way,” says Tommy Hancock, editor-in-chief of Pro Se Productions, a company publishing “new pulp” since 2010. “Pulp is fast paced, with a few exceptions. And, even those exceptions deliver a wham at the end that make up for the slow build up. Sides are clearly defined typically in Pulp, the good guy and the bad guy, even if the good guy in the story is a serial killer and the bad guy is a cop. As far as the story goes, how it’s structured, there’s still a good and bad presence. Then you throw in creative turn of phrase, intense description when appropriate, and basically an elegant manhandling of the English language. That’s Pulp.”

Over the years, pulp heroes have been explored and reinvented countless times. However, from the early years of the 20th century to 1957, the year Chester Himes’ goofy Harlem pulp For the Love of Imabelle, featuring detectives Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones, was published in America, the majority of those pulp characters represented were white men on a mission. Of course, there were exceptions, mostly peripheral characters of color that included Rudolph Fisher’s 1932 detective Perry Dent in the novel The Conjure Man Dies, actor Herb Jeffries “colored” cowboy Bob Blake in The Bronze Buckaroo and Harlem Rides the Range (both 1939) and the lone Negro astronaut in the classic EC comics story Judgement Day, but those stories were only occasional.

Back when I was coming of age, the pulp canon began to diversify. With the inclusion of Chester Himes’ madcap Harlem crime novels, John Ball’s gentleman detective Virgil Tibbs from In the Heat of the Night (1965), the rise of the blaxploitation era that introduced the world of Blax pulp heroes (Shaft, Cleopatra Jones and Black Caesar) and brown-skinned comic book superheroes that included The Falcon and Luke Cage. All of those characters bum-rushed my imagination and, years later, inspired more than a few of my own farfetched short stories.

Still, it wasn’t 2012, when my friend and writer extraordinaire Gary Phillips invited me to be part of a collection he was co-editing called Black Pulp that I got a chance to create my own sepia skinned pulp stars Jaguar and Shep as leads in the surreal tale Jaguar and the Jungleland Boogie. Combining my love for the year 1988, Harlem, hip-hop, jazz and abandoned schools, the piece was an offbeat detective story inspired by old school rap, Batman, Grandmaster Flash, The Shadow, Duke Ellington and Howard Chaykin graphic novels. Recalling Fab 5 Freddy, who appeared in the story, telling me about the jazz/hip-hop shows he did with Max Roach at the Mudd Club in the 1980s, the finished piece told the tale of a crazy be-bop lover trying to rid rap music from the streets of Sugar Hill.

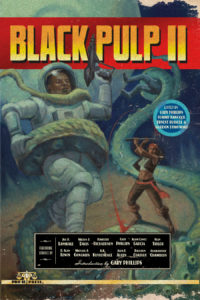

Black Pulp was published in 2013 by the then newly-launched indie Pro Se Productions, whose owner Tommy Hancock also co-edited the volume. In addition to my b-boy/be-bop tale, the cool line-up of creators inside included crime novelist and Eazy Rollins creator Walter Mosley, who penned the introductory essay, Derrick Ferguson, Gar Anthony Heywood, Christopher Chambers, Kimberly Richardson, Mel Odom, Joe Lansdale and Gary Phillips.

A respected novelist, comic book writer and TV writer, who most recently worked on the third season of the crack era drama Snowfall, Phillips is a California native who has been into pulp fiction since he was a teenager reading Chester Himes novels. “The idea of the original Black Pulp collection was not about being a gimmick,” Phillips says. “It was and is about fans of pulp and revisionist new pulp digging characters who reflect more than just the white guy playboy millionaire-scientist adventurer prototype. Often in the old pulps, if a person of color did show up, they were portrayed stereotypically (though there were exceptions like Josh and Rosabel Newton, the married aides of the Avenger and Jericho Druke, one of the Shadow’s agents). Black Pulp is not about being PC, but being entertaining and slam-bang, with some reflective attitudes woven in as well.”

Critic Mark Bould wrote in the Los Angeles Review of Books, “Black Pulp is tremendous fun. It shows us how far we have come, and how far we have left to go. It’s straightforward action-adventures conjure a sense of belatedness, of fiction oddly disentimed, while its insertion of black characters into pulp scenarios suggests an alternative history. One cannot help but wonder how different the world would have had to be for these stories to have been published in the old pulp era.”

This summer, six years later, Pro Se plans to publish the much anticipated Black Pulp II, with Gary Phillips and Tommy Hancock again at the editorial helm. Phillips says, “When Black Pulp first hit the scene there was blowback about it being an effort to be all SJW, Social Justice Warrior, a derogatory term. But, in fact Black folks, Asians, Latinx and so on have been around a long damn time and didn’t just come on the scene in the ‘50s, as some seem to think. Still, the work in that first collection spoke for itself and the book was a solid seller. We hope Black Pulp II does the same.”

When I was offered the opportunity to expand the Jaguar and Shep mythology with a new story (“Time’s Up,” named after a Living Colour album and single), I began revisiting, for inspiration purposes, various African-American pulp heroes as well introducing myself to new ones. Below are the soulful seven favorites that were an inspiration during the writing process.

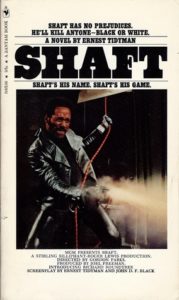

Shaft

In 1970 newspaper man Ernest Tidyman changed his life with the publication of his debut novel Shaft, a Black private detective in the tradition of Philip Marlowe and Sam Spade. He had an office in Times Square, but worked the mean streets of Harlem as he walked with a fearless bop in the hood and in Greenwich Village, drinking espresso at Caffe Reggio. While Tidyman’s book was popular, it wasn’t until Shaft was adapted by director Gordo Parks and screenwriter John D.F. Black, the following year that this action hero, as played by Richard Roundtree and musically celebrated in the Oscar winning theme song from Isaac Hayes, became a household name.

However, as novelist Nelson George says in the upcoming Sticking It to the Man: Revolution and Counterculture in Pulp and Popular Fiction, 1950 to 1980 edited by Andrew Nette and Iain McIntyre, “Richard Roundtree was charming on screen, but the Shaft in Tidyman’s novel is a richer character in many ways. In the book, the character is meaner. We find out his back-story as an orphan and Vietnam vet. None of that is even mentioned in the film.” Although the movie has stirred me since childhood, reading the novels, there were seven total, brought me closer to the character.

While the recent incarnation of the bad mutha was a mis-directed comedy also titled Shaft, in 2014 writer David Walker adapted the character to a short-lived comic book series collected in A Complicated Man and, two years later, the paperback original Shaft’s Revenge.

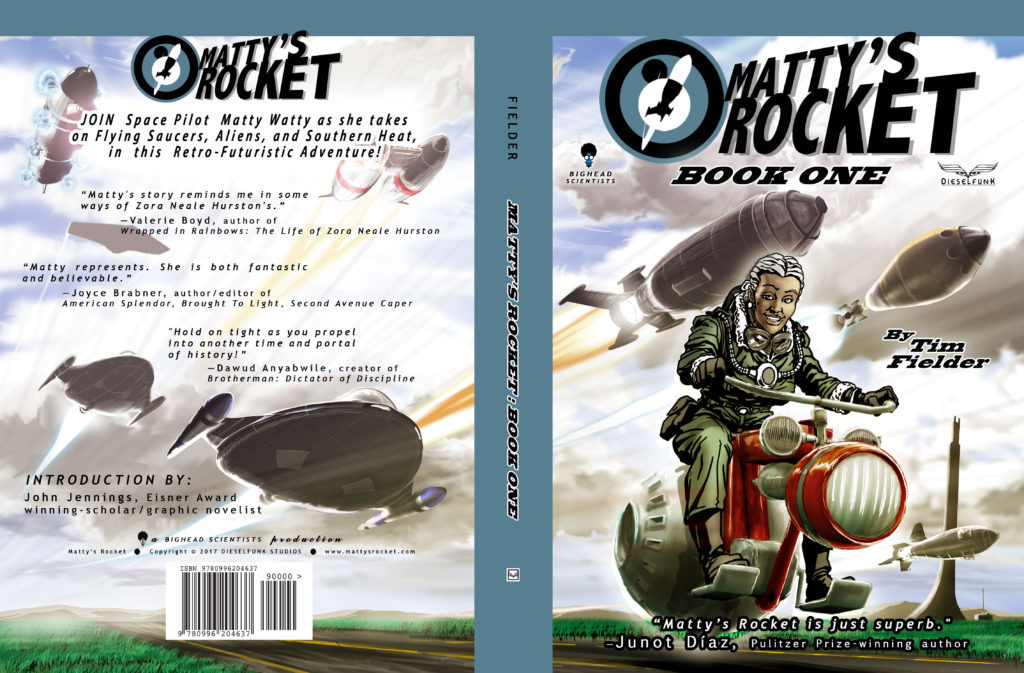

Matty’s Rocket

Written and illustrated by Afro-Futurist comic book artist Tim Fielder, the 2017 graphic novel Matty’s Rocket introduces us to Black woman astronaut named Matty Watty, who pridefully escapes the brutal Jim Crow south and relocates to Paris to become the person she was meant to be. Fielder, who has done comics, animation and illustration work for over thirty-years, combines his love for the red-dirt narratives of Zora Neale Hurston and Richard Wright with the future shock space-age adventures inspired by Dan Dare co-creator and artist Frank Hampson.

“Hampson had such a huge influence,” Fielder told writer Alex Dueben in 2018. “Dan Dare was ahead of its time. It was done during the fifties. Frank Hampson worked for Eagle Comics and he was the absolute truth. He was a man who knew how to use reference. He was a man that had no fear of putting his blood, sweat, and tears in his work and it showed.”

Personally, I loved how Fielder mixed the love and brutality of Matty’s life with the fantastic sci-fi possibilities of space travel and alien encounters. While this collection sets up the origin story of expat Matty as a star explorer, alien fighting pulp hero, I look forward to her further adventures. Best-selling author Joyce Brabner called the book, “joyful, encouraging and brave,” Much like director/producer George Lucas’ iconic Star Wars saga, Fielder boldly flaunts his influences while creating something fresh in the process.

Black Samurai

In the 1970s, in the wake of James Bond’s popularity, there was an explosion of action hero books that included the popular series The Executioner that debuted in 1969. Five years later, author Marc Olden, a former Broadway press agent turned pulp writer who began his publishing career writing a non-fiction book about Angela Davis, turned his talents to writing the Black Samurai series.

In the seven books that comprise the series, Olden told the tale of an Afro-American serviceman Robert Sand who, while on-leave in Japan, tries to help an old native he witnessed being attacked. When Sand passes out, the elderly man is revealed to be samurai Master Konuma, who beats his tormentors and takes the Black GI back to his home to train him. Of course, after Konuma is killed Sand’s vows revenge and sets out to kick ass. In addition to Olden’s fine writing, the covers were stunning images that reminded me of James Bama’s equally beautiful Doc Savage paintings.

According to Glorious Trash blogger Joe Kenney, “Marc Olden churned out this entire series within one year; a staggering feat by any means, but even more staggering when you realize that Olden’s writing is heads and tails better than just about any other writing you will encounter in this genre. I mean, there’s character development, there’s good dialog, there’s inventive setpieces.”

In 1977, martial artist turned actor Jim Kelly starred in a film of Olden’s creation that wasn’t very good. Forty years later, Common announced that he was going to play the character in a Starz television series produced by RZA and Jerry Bruckheimer, but, three years later, there has been nothing.

Action Jackson

How I missed the b-movie gem when it came out in my favorite year, 1988, I don’t know, but thirty-one years later this movie made my day. While the late singer/actress Vanity played the finest junkie ever depicted on screen, shooting-up H with her pretty silver syringes, Carl Weathers played the title character, a Detroit cop who, like James Brown’s poppa, don’t take no mess from villain Craig T. Nelson. In addition, burly Bill Duke played the cliched grumpy police captain to perfection. Of course, this movie is filled with bad one-liners, tacky ‘80s wardrobe choices and bad acting, but any joint that ends with the good guy driving his car through the front door of the bad guy’s house and up the stairs to the master bedroom is alright with me.

Brotherman

As a kid I grew out of superhero comics pretty quickly, though I did buy Captain America because of his Black sidekick the Falcon. Besides being one of the few superheroes of color who didn’t have the word “Black” in front of their name (props to Luke Cage too), the Falcon was a cool Harlem cat I would have liked to hang-out with on 125th Street. However, in 1990 I stumbled into St. Mark’s Comics (recently closed) and discovered the indie book. Produced by the brotherly duo David Sims, the artist who today goes by the name Dawud Anyabwile, and writer Guy Sims, the magazine sized comic featured Antonio Valor as a public defender for Big City who decides to become a costumed crusader when his community becomes too much.

“Antonio Valor was to embody the concept of the man who is upright and about his word,” Anyabwile told writer Victoria Comella in 2017. “He personified in our minds the black men in our communities who were disciplined, caring and protectors of their families and communities, yet go to their grave with no songs written about them. We wanted to celebrate those who deserved it in mythology.”

Although Brotherman wasn’t done on a strict schedule, publishing only eleven issues in ten years, each edition was better than the last. The Sims brothers followed their own artistic path that was inspired by painter Ernie Barnes, funk illustrator Overton Llyod and both the wordplay and sonic science of hip-hop. With each new issue, Anyabwile’s work got wilder, looser and better.

“The Brotherman comic was unbelievable,” says writer and popular culture scholar Shawn Taylor. “It was undeniably Black from the art aesthetic to the storytelling. We talk about representation now, but back then they did it without it being some kind of representation project. It was a fact and a factor of the contemporary comic landscape. For me, it showed that you didn’t have to jock the big three (DC, Marvel, Image). The DIY ethos was a marriage of hip-hop and what is considered ‘fine art.’ Brotherman was an invitation to be artistically brave and uncompromising.”

Ghost Dog

I can still remember seeing this haunting flick in Times Square on the first day it opened, twenty-years ago. A mashup of blaxploitation and samurai films, Ghost Dog was a ghetto arthouse picture that was simultaneously gritty and beautiful. As the homeboy samurai sleeping on a Brooklyn rooftop, caring for carrier pigeons and working as an assassin for the mob, actor Forest Whitaker put his heart into a role that was as Oscar worthy as his portrayal of Idi Amin would be seven years later. Directed by Jim Jarmusch, one of my favorite New York City filmmakers since his early Stranger Than Paradise, this moody movie was an inspired love letter to genre cinema and the New Wave cool assassin in Jean-Pierre Melville’s brilliant Le Samouraï. While writing the script, Jarmusch used the aural eeriness of the Wu-Tang Clan albums.

“Of course it’s only right that he got (Wu Tang producer/conceptist) RZA to do the score, which for the most part fits the muted atmosphere,” says writer S.H. Fernando, who is currently working on a book about the Wu. “The Ghost Dog soundtrack is inextricably linked to the film in that the music makes continual references to the film, including actual snippets of Forest Whitaker’s dialogue (or in this case monologue). Of course, this comes as no surprise considering that The RZA was well-versed in the genre and even sampled many blaxploitation classics in his own productions.”

Twenty years later, Ghost Dog has aged well, and really captures that late 90s zeitgeist of the ghetto mystic/urban warrior.

Kenyatta series

Living in Harlem in the 1970s, there was no escaping Holloway House publications. In addition to publishing the black Playboy inspired Players, which once featured a spread with blax-action queen Pam Grier, Holloway also produced a slew of hood adventure and crime paperbacks that were sold in record stores, head shops and newsstands. Perhaps the only place you would not have found them were in bookstores. Still, with a stable of writers that included Iceberg Slim, Robert H. deCoy, Jerome Dyson Wright and Donald Goines, they were the kings of “street lit” years before the genre was given a name

Inspired by Slim’s seminal Pimp, junkie scribe Goines started writing while he was in prison and kept at it steady until his murder in 1974. Having authored fifteen books in three years, the four books in the Kenyatta series were written in 1974 under the pseudonym of Al C. Clark. Beginning with Crime Partners, the Kenyatta books are both political in a revolutionary sense and fantastical in the James Bond sense, with the main protagonist running a crew of revolutionaries that reminds most readers of the Black Panthers.

“Kenyan president and anticolonial freedom fighter Jomo Kenyatta is at least the symbolic inspiration for the Kenyatta character,” says author/professor Kinohi Nishikawa, whose book Street Players documents the Los Angeles based Holloway House. “Early on there’s brief mention of anti colonial/Third Worldist propaganda in one of Kenyatta’s rooms. But, a more ineffable inspiration for Kenyatta’s group may be Chicago’s Blackstone Rangers, the street gang-cum-revolutionary cadre, about whom Gwendolyn Brooks also writes. The Kenyatta series could be read as an extension of his thinking about what it means for gangs to collectivize and radicalize.”

Goines biographer Eddie Stone wrote that Kenyatta was the writer’s most “interesting character.” While I would agree, I also found it compelling that Goines used a pen name on these books. “The real Al C. Clark was Goines’s childhood friend from Detroit,” says Nishikawa. “Holloway House co-publisher Bentley Morriss was ostensibly the one who recommended the switch: ‘We want to publish the books, but if you put out too many books of an author within a given period of time it has a sham about it. Would you consider putting a book out under a pseudonym?’ As a pen name, Al C. Clark gave Goines the cover he needed to publish a rip-roaring action serial—something he hadn’t done before. Goines’s previous books were standalone titles—self-contained narratives, usually about inner-city violence and vice. By contrast, the Kenyatta story was to be an action serial, with the plot extending over as many books as could handle it. As Clark, Goines would be able to ‘start fresh,’ as it were, and take his writing to a new place.”