“Something foul” was in the air, and the ominous stench put a quick end to the morning’s fun. On July 14, 1976, six years after Stamford’s potter’s field was abandoned by the city and the land had become choked with bracken and vine, a high school teacher took his mom and a cousin on a hunt for lost grave markers. And they were just that. Markers. No names, no dates, only numbers chiseled on gray stones set into the dirt like those used to indicate property lines. But it was Stamford history all the same, and somewhere, I’m guessing, secreted in the basement of the historical society, sits a moldering book wherein those numbers reveal the stories of the dead.

I understand the appeal a place like the potter’s field had for this family. I am drawn to old graveyards myself. My daughter jokes that when we went to Paris in 2006, we spent more time tracking down Jim Morrison’s littered slab in Père Lachaise cemetery than we spent at the Louvre. “What’s your point?” I asked her, but I knew the point. I’ve always liked to view the past through the prism of something physical and weighted with meaning, something like a grave.

On the morning of the Stamford field trip, it was not just hot, it was steamy. It had been showering off and on for more than a week without ever drying out, making for an oppressive day. The air had weight. Mosquitoes drifted in search of a blood meal and storm clouds gathered on the horizon, but the teacher and his family paid them no mind. Curious about what they might discover, they were cheerfully absorbed in their investigation, tramping through the overgrown landscape, calling out discoveries and moving dank brush aside with their hands, until, with a start, they recoiled at the first whiff of decay. The teacher, a bit apprehensively no doubt, followed the odor into a cedar thicket, where their worst fears were made fact. An animal, grubbing for meat, had scratched around a shallowly interred corpse, exposing an arm and the top of a foot, both streaked with green and black, the colors of late-stage rot.

For exactly one hundred years, the potter’s field had been the dumping ground for Stamford’s indigent, unclaimed, or unidentified bodies.For exactly one hundred years, the potter’s field had been the dumping ground for Stamford’s indigent, unclaimed, or unidentified bodies. Whatever their lives might have been before, whatever their age, gender, or color of their skin, in the end they were all roughly discarded by some city worker. The bodies were thrown together, one on top of another, sometimes without so much as a box. Criminals and the young were often just wrapped in cloth and lowered into the earth. The first shovel of dirt was lifted in 1870, soon after the Civil War, and the last mound was tamped down in 1970, when the field closed. Maybe the plot was finally full to overflowing. More likely, the law changed and the city was allowed to cremate the bodies instead, an option that took up no real estate at all. The graveyard, such as it was, fell into neglect, and because of its isolation it became both a druggie hangout and a lover’s lane, a place of potential danger in either case. The police did not patrol the area. As for me, I never visited the field during the two years I lived in Connecticut, and for that much I am grateful.

Before the body in the potter’s field had a name, the coroner at the next day’s autopsy estimated that the white female had been dead for more than ten days. A final meal of fried chicken and coleslaw was still in her stomach. And even though the police, insect-like in their gas masks, had originally reported no signs of foul play when they exhumed her, the coroner found an arrowhead used for hunting big game piercing her heart.

A bow and arrow is a weapon powered by the tension between two opposing forces. The farther the clenched fists push forward and pull back, the more energy is released in the form of an arrow and the greater the penetration into the mark. In this case, the arrowhead was buried so deep the killer couldn’t pull it out. The shaft was snapped off inside the ribs, which means someone had walked away from the body clutching a jagged stick with heart tissue still clinging to it. After an anonymous tip to the police, days after the body was found, Margo Olson was identified by dental records and claimed by her mother.

When this news first appeared in the paper in July 1976, I stared at it in horror and could hardly comprehend the words. I only knew Margo at the end of her short life, her last year, when she seemed to be falling apart, and yet her death produced such fear that I promptly buried her and put her out of my mind. Decades later, just at the point I had trouble even recalling her name, her death slowly became as vivid to me as if she had just been murdered. It took that long for the words to sink in. It took much longer to understand my fear. Since then, I have tried to gently brush the dirt off her face with my hand to get a better look, contemplating the shape of her hurried grave and wondering what brought her to that place. But I can only follow her back to a certain point, and she can never follow me here. I doubt that she would want to come with me if she could. She would not want to leave the one she loved.

I have tried to gently brush the dirt off her face with my hand to get a better look, contemplating the shape of her hurried grave and wondering what brought her to that place.It took time, but after sifting through the disturbed earth for so long, I can now envision the tall, striking young woman Margo had been. Growing up in Darien,* a top-shelf community abutting Stamford to the east, she’d been a Girl Scout, taught Sunday school, and sang in the church choir. When her parents divorced, her father retreated to Kentucky and Margo seemed to show no regret. At the time of her death, her mother had remarried and was living a few miles away in Wilton, another affluent town. By all accounts from those who knew Margo in Darien high school, she was a smart, artistic student who loved backgammon and played a decent game of tennis. There was always what a friend called “a certain sadness” about her. After high school, she went to Fairleigh Dickinson University in New Jersey, where she graduated with a degree in childhood education.

All in all, she seemed an unlikely candidate to end up as a body dump. But she, like so many other young women at the time—women like me—had wandered off the main road searching for something we couldn’t even name. We were inchoate desire and just hoped we’d know what we were looking for when we found it.

Margo and I met in the fall of 1975, when I was eighteen and she was twenty-four. My first impression was that she looked like Janis Joplin, so recently deceased, with a soft, suspicious face that peered through a curtain of peachy hair. Margo didn’t talk so much as mumble, making it hard to tell whether she was trying to communicate with me or with someone in her head. She dropped acid on a regular basis, so it was unclear whether her strangeness was a result of drugs, or whether she was self-medicating a legacy of preexisting problems. Outside her boyfriend’s circle, of which I stood on the periphery, she had, like me, few friends of her own in Stamford.

It was not our town. Margo was just that much older, and just this side of odd, so she was not someone I would have known if I had not been living with Joe Louis, who was friends with her boyfriend, Howie Carter. Howie and Margo were another interracial couple in town, like us. Both men were black, both women white. Howie was a suspect in Margo’s murder but was never charged. He did not leave town. He did not run. A few weeks later he was shot and killed by the police.

Howie was a suspect in Margo’s murder but was never charged. He did not leave town. He did not run. A few weeks later he was shot and killed by the police.America’s bicentennial was a time of renewed reverence for the past. In that spirit, Joe created our own history for 1976, but it’s proved to be an unconvincing narrative. The story that I bought from Joe was that the police, who in Joe’s lights were capable of any atrocity, did not have the evidence to convict a presumably innocent Howie for Margo’s death, so they killed him instead, and—like everything else in Joe’s black-and-white world—it was racially motivated. And who can say he was wrong about that? Not me. Not by a long shot. But Joe never addressed the issue of who might have plunged the arrow in Margo’s heart, as if her death were a mere accessory to Howie’s wrongful one, and I never asked.

I never asked.

To be fair, and I want very much to be fair, I was the one who read what I wanted into the story. If prejudice means to prejudge, then I stand as guilty as anyone else. I made assumptions. Race was a red herring that dragged my attention away from Margo’s murder back to the unjust society we lived in, a jagged hole of racial tension so big it could suck up something the size of a dead body and make it disappear. I was wrapped in a shroud of oblivion and privilege I had stitched by hand. Even to wonder aloud who might have killed Margo seemed a dangerous misstep at the time. The arrow pointed both ways, at the woman who lay half buried in the underbrush, then back at me.

In a vivid dream I had early in the long writing of this book, I was getting a psychic reading. The psychic, an older woman, had a handheld device that she claimed was going to reveal a number to help with the reading. The numbers on the screen whizzed by in a blur, one after another like the years, and then a message appeared. The psychic said that a dead woman wanted to communicate with me, was that okay? I said sure, thinking the psychic would channel her, but I was the one who started speaking for the dead, screaming “Go away, leave me alone,” over and over. I woke up with my heart pounding somewhere on the other side of the room.

*Nicknamed Aryan Darien, it was the setting for the 1947 Gregory Peck movie Gentleman’s Agreement about an anti-Semitic community.

__________________________________

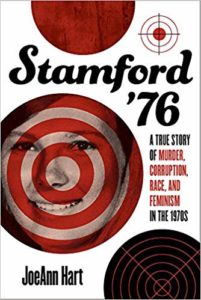

From Stamford ’76: A True Story of Corruption, Race, and Feminism in the 1970s. Copyright © 2019 by JoeAnn Hart and reprinted with permission from University of Iowa Press.