DAY ONE, 7:00 a.m.

My wife and I walk our dog at dawn. We live across the street from a little lake connected by a channel to Florida’s St. Johns River, which, eighteen miles away, empties into the Atlantic Ocean. Even so far from the ocean, the lake is tidal, eventually refreshing its old brackish water with new brackish water. But in summer months when the lake is still, Day-Glo green algae scums the surface. It’s a terrible place to dump a body.

Our dog Louise, a boxer mix named for Joe Lewis, runs ahead of us and sniffs at the ground beside the lake. She’s a tough old dog, dragging a hind leg years after a car hit her, the muscle above the leg carrying buckshot from a murky past before we adopted her. If she ever felt pain you wouldn’t know it as she noses happily through the grass and weeds. Life is good.

Then, at the next street, visible a quarter of the way around the lake, a firetruck pulls to the curb—lights flashing, siren oddly silent.

We decide to go that way.

7:05 a.m.

As we round the corner, one of our neighbors walks toward us as if unsure of his own feet. A tall man in his thirties, he usually has an easy smile. He looks stricken. Minutes ago, he saw a body in the water. A boy, he thinks, eight or nine years old.

He called 911.

He waited for the firetruck.

Now he stumbles home to his partner, who is pregnant with their first child.

My wife and I stand at the corner, stunned, momentarily unable to go farther or turn back.

A boy. How did a child end up in the lake at dawn? Did he wander out in the early morning dark, looking for . . . what would a child search for before sunrise? Did he sneak from his house in the night as his family slept—to meet friends or go on a solitary adventure? Did he somehow . . . but how? . . . fall into the water and drown? Were his mom and dad tapping on his door right now, expecting to wake him, opening his door, finding his bed empty?

Damn.

7:20 a.m.

With stunning speed, the neighborhood has heard about the body in the lake. We stand together in the street, naming the families that have eight- or nine-year-old boys—trying not to imagine, finding it impossible not to. The police tell people who live near to where the body was found to stay in their houses. Then someone says there’s blood on the pavement by the lake.

8:30 a.m.

A neighbor, quoting a source she doesn’t identify, says the body wasn’t an eight- or nine-year-old but a small man in his early twenties.

The news comes as a relief. There can be nothing worse than a dead child.

But my own kids are in their early twenties. The fist pulls from my gut only to hit again—deep, deeper. I’m ashamed to admit it, but now the death feels more personal.

Still, no one can explain how a young man ended up in the lake, how blood stained the street. The neighbor says, “Hit-and-run,” and this becomes the accepted story, one we might be able to sleep with. But if a hit-and-run, then what? After hitting a man, the driver dumped the body in the lake?

10:00 a.m.

Another neighbor, in one of the close-by houses, tells a new story. The body was a teenage girl. This neighbor could see her in the water before the police pulled her out. She was fully clothed, including socks, but wore no shoes.

Socks.

Through the day, investigators work behind crime-scene tape. Divers comb the lake bottom. News reporters stand on a facing bank, zooming their lenses, then knock on doors, asking for reactions.

In the evening, the yellow tape comes down, and the police and reporters drive away.

There seems to be a hole in the neighborhood.

DAY TWO, 7:00 a.m.

The next morning, my wife and I walk our dog.

Across the street, a man is fishing in the lake.

Should we tell him? Say, This water is holy or This water is taboo or Don’t eat the fish.

Our dog drags her bad leg. She noses happily through the grass and weeds.

Later, after the chaos of uncertainty and misinformation, the police announce that the boy-man-teenage girl was really a twenty-three-year-old woman. Her family and friends describe her as a “hardworking mother” who “would do anything for her children.” The police charge her boyfriend with killing her— and then, in a tangle of stories and counter-stories, drop the charges against him.

The news stations report her name.

Her name was Beverley Febres. We have that much.

* * *

I have a weak stomach for death. That’s partly why I write murder mysteries—as a way to put what I fear into a plot with a beginning, a middle, and an end-that-isn’t-really-an-end but a last page after which I can start a new story. As if putting words on paper might slow the inevitable.

But writing fiction is also a way of facing death—looking into its fearsome eyes, working through its possible storylines, and learning its name. I would never write a true crime book. I can hold the gaze for only so long before I need to turn away. But the more novels I write and the more I read, the more I want stories that go after the true—the more-than-plausible: the real.

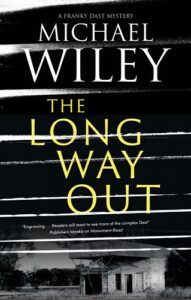

Like many other writers, I’m trying to improve my eyesight. I want to see the world for what it is and might be. In my own The Long Way Out, ex-con Franky Dast investigates three murders. The dead—a girl from Jalisco, Mexico, a man from Punjab, India, and a woman from the Dominican Republic—are fictions who live in a real world of anti-immigrant violence. As Franky looks for answers, he learns about some of the other immigrants who have been killed in America. These people aren’t fictions, and Franky learns some of their real names. They are José Luís Tías, Mateo Gomez, Felipe Mauricio Esparza, Pedro Corzo, Mauricío Florindo, José Sucuzhañay, Armando Perez Martínez, Marcelo Lucero, Luís Ramírez, and Guadalupe Sanchez.

How much power is there in a name? Is writing names like these into a novel an empty gesture or, worse, an attempt to simplify and contain in entertainment the huge complexity of real lives and deaths?

I’m still working on that one. But I do know that I admire Maya Lin’s Vietnam War Memorial with its one hundred forty black-granite panels naming nearly sixty thousand dead and missing. And I admire William Butler Yeats “Easter 1916,” about the Easter Rebellion in Ireland. Britain executed sixteen leaders of the uprising, and Yeats struggles to make sense of the deaths. He knows the inadequacy of his own words, but still decides that “our part [is] to murmur name upon name” of the dead. He names four: “MacDonagh and McBride and Connelly and Pearse.” Naming the dead might not change the world, but it seems to me that the failure to name the real—to memorialize, to carve the names into our consciousnesses—will ensure that we will forget and that no change occurs.

***