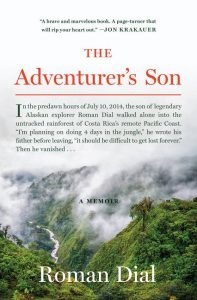

In the predawn hours of July 10, 2014, the twenty-seven-year-old son of preeminent Alaskan scientist and National Geographic Explorer Roman Dial, walked alone into Corcovado National Park, an untracked rainforest along Costa Rica’s remote Pacific Coast that shelters miners, poachers, and drug smugglers. He carried a light backpack and machete. Before he left, Cody Roman Dial emailed his father: “I am not sure how long it will take me, but I’m planning on doing 4 days in the jungle and a day to walk out. I’ll be bounded by a trail to the west and the coast everywhere else, so it should be difficult to get lost forever.”

They were the last words Dial received from his son.

As soon as he realized Cody Roman’s return date had passed, Dial set off for Costa Rica. He was accompanied by another experienced explorer, Thai Verzone. On the ground, Dial faced the enormity of the task in front of him. The rainforest was vast and difficult terrain. There were rumors swirling among locals and law enforcement about a man known as Pata de Lora, who had been seen with a white backpacker, possibly Dial, and who claimed there had been an abduction. Volunteers soon assembled to canvas the jungle. Cody’s exact route was unknown.

In the following excerpt from The Adventurer’s Son: A Memoir, Dial recounts the early days of the search in Costa Rica.

___________________________________

After dinner, Dondee informed us there’d be a helicopter search in the morning. This suggested in actions, if not words, that somebody besides me was not fully convinced by Pata Lora’s story. Or that Doña Berta from the Corners Hostel had convinced Dondee that Cody had gone back into the jungle a second time—and not come out.

More likely, the helicopter search was a response from American pressure to look more thoroughly. Since the day I left Alaska, the state’s lieutenant governor, a friend of mine named Mead Treadwell, had been pushing for U.S. National Guard involvement. Ultimately, Mead’s push for military assistance would reach the four-star general in charge of the Southern Command, General John F. Kelly, one step below President Obama’s Secretary of Defense.

Thai and I went back to the Iguana and heard the story of Pata Lora there, too, a narrative ossifying like a plaster cast across the Osa. Whenever one local whispered “Pata Lora,” another nodded solemnly, or twisted his face in a grimace. Maybe frontier justice was a simple matter of picking the local pariah for the most recent crime. Innocent or not, truth be damned, at least they’d be rid of the rat.

Depending on who was talking, Pata Lora was currently being held for drugs, theft, even murder. Pata Lora told the OIJ that the gringo paid him from an ATM on July 16, after Roger Muñoz had seen them in Carate. Here was something tangible that we could check: when did Roman last withdraw money?

I filled my notebook haphazardly with scribbled names, numbers, notes, and quotes. Still half convinced Cody Roman was around somewhere, but just too stoned to check his emails, I’d written in the margin, “We could just wait for him to walk out—but too many people involved, too much momentum.”

Back at the Iguana, Thai and I shared a room stuffed with gear. He wore his long black hair in a ponytail that reached past his shoulders and a choker of dzi and other beads he’d bargained hard for on our trip to Tibet the year before, when we had searched Himalayan glaciers a second time for ice worms. Thai was an adventurer who could do everything—climb, boat, ski, paraglide, hike fast, mountain-bike, navigate, save lives. Importantly, with his golden-colored skin and almond-shaped eyes, he fit in everywhere he went. People welcomed his warm smile, easy laugh, and honest enthusiasm.

“We gotta get to the Conte River, where Roman said he was going,” I implored. “Cruz Roja doesn’t seem to believe he ever went there. And this Pata Lora story—much as I wish it were true—it doesn’t seem right. If Roman came out, he would’ve contacted at least his friends, if not me and Peggy.”

Thai frowned sympathetically. “Yeah, I know. But first we have to establish credibility with Dondee and the park service. We have to show we are capable in the jungle without making mistakes. Accidents happen and with us wandering around out there . . . well, we could create another rescue situation. That’s their concern.”

Thai was right, of course, but my son was missing. My son, who I hoped would be twice the father I tried to be. I’d seen Roman’s tender side, an easy patience, and playfulness with little kids—qualities that are rare in young men. Besides, parents who want kids—like Peggy and me—usually want grandkids one day, too.

Instead of wringing my hands in town, where all I could do was mull over why this Pata Lora story wouldn’t go away, I wanted to search in the park myself. That’s why I had come, even if everyone saw me like Joe’s dad at the Anchorage airport carrying downhill skis, desperate to find his son on a wild mountain glacier.

By our second morning in Costa Rica, the euphoria that Roman would walk out at any moment was gone. The previous night’s relief on the phone with Peggy was a momentary peak on a roller coaster now plunging toward fear. Thai and I drove to the search headquarters where we were briefed—and questioned—by the Cruz Roja, MINAE, and Fuerza.

Cody hadn’t appeared. With posters everywhere, it seemed impossible for him not to have seen his own face somewhere on the Osa.

By our second morning in Costa Rica, the euphoria that Roman would walk out at any moment was gone.

Dondee stood in the briefing room full of searchers and told us all a helicopter with infrared search capabilities was winging its way from San José. He moved among the Cruz Roja volunteers, nodding his head when spoken to, hands on his hips or shaking a finger when speaking, his arms giving orders. Thai and I noticed we weren’t the only ones uncomfortable with Dondee. “He’s like a ballerina needing attention,” a local Tico nature guide whispered.

The Cruz Roja were mostly pale men from San José. They sat in chairs wearing earnest expressions and khaki uniforms tucked beneath their belts. Along the wall stood lean, scrappy guys, dark from the sun, shirttails free. These were the local rangers who knew the park, its miner and poacher trails, its ridgetops and canyon bottoms. They were the ones I wanted—especially the young ones—for a search team of my own.

The Fuerza asked me if we had any enemies. Was there anyone who’d do us any harm? I thought of emails Roman’s friends shared that mentioned finding a Costa Rican girl. I wondered if he’d pissed off a boyfriend or even a husband somewhere. Roman also had a dark, aggressive side I’d always suspected but never seen. Some bravado in emails to friends hinted at it, and now my imagination ran with the suggestion.

“No,” I replied. “None that I know of.” “Did he have a phone?”

“No, it was stolen in Mexico.”

“A GPS?”

I’d heard the gringo with Pata Lora had a GPS. “Not unless he bought one down here.”

“How about Facebook or social media?”

After the loss of his girlfriend and Vince’s death, Roman stopped using Facebook. “It’s just a bunch of people who don’t do anything, bragging about it when they do,” he explained. I had wondered, though, if it wasn’t because of his ex-girlfriend’s social media presence.

“He keeps in touch with email,” I told the Fuerza.

Again, I brought up the emails he had sent about the guide requirement, his intentions to go solo and off-trail, that maybe he was preparing to cross Panama’s Darién Gap.

“The volunteers are excited to find your son,” Dondee said, looking me in the eye. He continued in English. “These guys live for this. They live for this! ”

“That’s good.” I nodded sincerely, smiling. “That’s what we need. I’m so grateful for all these people who are helping. I don’t want them to stop.”

Then I reemphasized that Roman said he was heading in off-trail.

“The park superintendent says that off-trail travel in Corcovado is ‘illogical,’” Thai translated. The whole thing felt like an exam and I was giving only wrong answers.

“Tell them, ‘When he traveled off-trail in Guatemala he marked his route.’ ”

“How did he mark his route?” a ranger asked.

“By cutting with a machete,” I said, though it felt like another wrong answer.

“Everybody makes those marks,” Thai translated back, continuing: “Did he ever leave little reflectors?”

“What?”

Thai spoke in Spanish with a ranger. “Like thumbtacks. Did he ever leave thumbtacks? The guy with Pata Lora had left reflective thumbtacks in trees.”

This actually sounds like something Roman might try. It seemed clever, like the way he would mark small mammals by clipping their fur during live trapping projects. Reflective thumbtacks would be simpler than a machete but much harder to follow, except in the dark with a headlamp, perhaps.

“It’s possible,” I said, cautiously. But why would he mark a tourist trail while carrying a GPS and following a guide? It’s like wearing a belt with suspenders on a one-piece suit.

My mind sorted through these new questions as I left headquarters and headed for the airfield where the helicopter waited. The sturdy, compact black machine held five of us. No one but me spoke English. The effort reminded me of another search a decade before.

In Alaska, where the woods are open, I had once chartered a helicopter to search for three teams overdue in a Wilderness Classic I’d organized. One racer had positioned herself on a bald hill with a smoky signal fire; she was easy to find. I never found the others hidden by Alaska’s short-statured forest. How will we find someone beneath a forest three times as tall and five times as thick?

* * *

WE LIFTED OFF. I looked down at a rural landscape of cattle pastures and subsistence farms. The patchwork gave way to steep, forested mountains. We buzzed low outside the park between Dos Brazos and Piedras Blancas, where Cody reportedly followed Pata Lora. The only surfaces visible were the flash of streams, the dirt of landslides, the pastures of Piedras Blancas. Mostly, I saw billowing green crowns and the occasional slender white trunk in a tangled forest canopy. Banana-like heliconia plants obscured old landslides. Bracken ferns covered new ones.

The most recent slides, still raw with bare dirt, drew my attention.

Such a dynamic landscape.

We strained to see some sign of Roman. A flash of color that he might position on a creek’s gravel bar or still-water pool, or some gear he might drag onto the fresh surface of a new landslide. But there was nobody. Not a miner, not a tourist, and no lost and injured young man.

I couldn’t help but appreciate the effort, the cost, the futility. I wanted to see him there.

I couldn’t help but appreciate the effort, the cost, the futility. I wanted to see him there. But peering at the surface of an ocean of green foliage made it clear why everyone hoped Cody was on the trail to Carate, smoking pot with Pata Lora, or hanging out in a bar in Matapalo. Finding him outside Corcovado at least seemed possible.

Fourteen minutes after leaving Puerto Jiménez, we reached the Pacific. We circled over its aquamarine near-shore waters, then dropped off a Cruz Roja volunteer on the beach near Carate. It felt useful to have so many eyes on the ground. We flew back to Puerto Jiménez over the park’s north and west side. From the air, Corcovado’s mountain range looked like a clenched fist, palm down, knuckles as highpoints, the back of the hand sloping toward Dos Brazos, the finger joints forming cliffy canyon rims above the north and western rivers: Sirena, Rincon, and Claro—Roman’s destination. Here and there enormous trees with yellow blossoms punched through the canopy and waterfalls plunged off the summit escarpment. It was beautiful, futile, heartbreaking. He’s likely out of food by now.

I hoped that the helicopter signaled to him we were coming, that we would find him. The helicopter flight was useful in another way, too. It confirmed that to find Roman I needed to follow his trail into the jungle and retrace his route. Fifty minutes later we landed back in Puerto Jiménez. Officials would ultimately log over nine generous hours of helicopter time. I was grateful for the effort, even if disappointed by the not unexpected outcome.

After the flight, Thai and I returned to the Corners Hostel to see if Roman had come to pick up his things without telling us. Doña Berta said she was sorry that my son was missing. She said God would help. Then she asked me to take the yellow bag and not come back.

___________________________________