Dump the body in a bog. Pin it to the mucky bottom with willow branches so the corpse does not float to the surface, and eventually the decaying moss and vegetation will pickle the victim. The skin will darken, and the hair turn red from the biochemical stew. As the bog dries out over decades and centuries, the peat encases the victim.

A thousand years pass and another thousand, until one day farmers digging for peat to dry and provide fuel for a long Irish winter, turn the spade a discover a foot or a hand or the whole body. All signs point to foul play. A perfectly preserved noose circles the neck, or there’s the telltale blow from a club, or a gash at the throat. Murder? Or a sacrifice to the pagan gods.

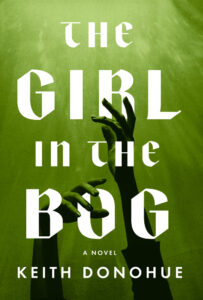

The dead are often the best narrators of their own demise. In my new novel, The Girl in the Bog, I wondered: what if the victim was a figure drawn from Irish mythology, the tangible proof of an ancient story? And what if her discovery opens a crack in time when legendary come roaring into the present day to reprise their old animosities.

I turned to one of my favorite stories, “The Cattle Raid on Cooley,” a kind of Irish Iliad. By turns bawdy and bloody, filled with exaggeration and blather, the story concerns Queen Medb of western kingdom of Connacht, who raises a vast army to steal a prize bull from the northern forces, protected only by the larger-than-life Cúchullain, the Hound of Ulster. As Medb’s troops march into battle, they meet Fedelm, a young poet with the gift of “second sight.” She issues a dire warming, predicting defeat at the hands of Cúchullain, who will stain the Irish countryside in “crimson and red.”

Centuries later a pair of farmers dig up Fedelm. She is restored back to life, and so, too, are Medb and the Hound of Ulster, both determined to find her, and the chase is on. With the aid of three wannabe red-headed witches, Fedelm makes her escape, always wondering which of the two foes had murdered her 2,000 years ago.

“The Cattle Raid on Cooley” gave me the backbone of the plot and major characters, adapted to suit my dark purposes. The epic builds suspense through the extraordinary military prowess of Cúchullain versus the battle smarts of Medb. Simply re-telling the myth, however, is not enough. In keeping with the Irish spirit of the thing, I had to add more comic relief. Where better to look than the Otherworld.

To the mix of the two comical farmers who discover Fedelm and the three witches who help her escape, I added a death-obsessed American archaeologist named Bridget Scanlon. As all these characters move through the moonlit night, they encounter from folklore a troupe of Irish fairies to help or hinder as they see fit, and a banshee who would rather be watching cowboy movies than working her magic. Curiously enough, some of the old ways persist. Never cross a fairy ring, or speak the real name of the Good People, lest they be listening.

While Fedelm’s murder is the heart of the matter, other crimes pile up: breaking and entering, vandalism, cattle rustling, and yes, there’s another murder, a bash in the head, at the climax of the tale. All told with an ear to the blather and music of they way Irish people talk.

Of course, novelists and storytellers have been mining mythology as source material for ages. Longtime readers of CrimeReads might remember Emily Littlejohn’s Seven Mystery Novels Featuring Myths and Fairy Tales or the recent popular success of Madeline Miller’s Circe and the Song of Achilles. Or anything at all by Neil Gaiman. Irish novels as disparate as James Joyce’s Ulysses and Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds put a Celtic twist on the matter.

My own work, whether in novels about changelings or angels, puppets or monsters, has always been about that strange propensity we have to believe in things we cannot see, reaching into the uncanny secret life of other worlds as vivid in our imaginations as “reality.” All fiction posits the same escape from the humdrum, creating new worlds out of type on paper.

We reach back into the past to mine the classics because those myths and folklore re-enchant our everyday world. They bring us the larger-than-life figures and dramatic situations absent from modern life, and heighten the very real emotional life that drives stories. Cúchullain may be the great Irish hero, yet in my version he still pouts when he’s bested at a game of chess. Medb may be the great Irish heroine, yet she feels pangs of jealousy over her husband’s flirtations with another woman. Fedelm, long buried in a bog, deserves a second chance at life. And the fairies, too, prove fond of a clever dog and the simple pleasures of weaving a puzzling riddle or a mystery spiraling and weaving on a midsummer’s night.

Irish mythology and folklore belie the twee sentimentality associated with the Americanized version of Irish culture, with its marshmallow leprechauns, green beer, and the wearing of the plastic shamrocks. Its roots are as deep as the boglands, with remarkable stories filled with laughter and cruelness, hope and great sorrow, strong men and stronger women. Grudges die slowly. Ancient crimes remain unsolved. Ripe soil for a storyteller.

***