Two old friends currently visiting, one from London and the other from Berlin, are making serious inroads into my chicken coop for the soft-boiled eggs they now consume each morning. They cannot get over their surprise at the deep yellow colour, or the variety of size and shapes that my hens, of various breeds, deliver. Most of all, they are surprised when I tell them they are eating second-hand leftovers because when it comes to the diet of free chickens in the French countryside, anything goes.

All plums, pears and apples that get bruised, when they fall to the ground before I can pick them, go to the chickens. And so do all potato peelings, onion skins, tops and tails of carrots, cucumber skins, melon rinds and seeds, fat trimmings off the ham, barbecued ribs with some shreds of meat still attached, cheese rinds, stalks of mushrooms, orange peel and apple cores. Stale bread is soaked first but they devour that, too.

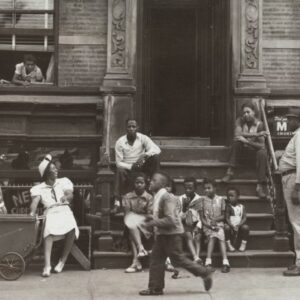

We went down the other evening to our village’s weekly night market, where about five hundred people gathered at the tables and benches in the square by the rover, with a space for dancing later, and all around the rim were the food stalls. They offered Thai food, the German pizzas called Flammkuechen, Caribbean food from Guadeloupe, Indian vegetarian curries, flame-grilled hamburgers, ice creams, apple tarts, dozens of different cheeses – and all the classic French country food. This includes roast beef, lamb, pork and duck, fresh-grilled fish and prawns along with flash-fried foie gras, pommes frites, huge tomato and cucumber salads.

What my friends had not expected was that, once we had eaten, I pulled out the two large heavy-duty plastic bags that I keep for these occasions and went along all the rows of benches looking for leftovers. I asked politely for any déchets, or rubbish, explaining that it was ‘pour mes poules.’ Among the French this causes little surprise but the Dutch and British and German tourists are usually startled by this request. But they soon enter into the spirit of the thing and start loading the bread crusts, cold french fries, remnants of salads and churros and melted ice creams and everything imaginable that is edible into the sacks.

When the evening is over, I empty the heavier of the two bags into the main chicken coop where the mature females live with their cockerel, Macron, named for the French President. (The last cock was called Sarko, for President Sarkozy, and he came with four wives. The pretty one was named for his wife, Carla Bruni. The second one was the bully, always the first to eat, so we called her Margaret Thatcher. The third never stopped clucking, so she became Hillary Clinton and the fourth laid the most eggs so she became Angela Merkel.)

The second bag is emptied into the smaller coop, that is at once the maternity ward, nursery and kindergarten for the new newborn and young chickens who will eventually be moved into the big girls’ coop. It is also home to two motherly old hens and a couple of pheasants who found their way in by accident. But that’s another story. By the time we wake up in the morning, the heaped piles of leftovers have all gone but the hens and chickens still want their morning feed of cracked maize. And in return they leave the finest eggs we have ever tasted, white and brown, speckled and uniform, round or oval in shape, but each with the glorious sunshine-golden yolk that feels like the richest food of all.

***