The Brooklyn Children’s Museum is a two-mile walk from my apartment. It’s an inviting edifice, filled with magic and wonder for children and adults alike. The surrounding grounds are peaceful, punctuated by the boisterous sounds of little kids going in and out of the museum. For good reason it’s a jewel of the borough, attracting over 260,000 annual visitors.

A block south and across the street from the museum is a four-story dilapidated townhouse. It ought to be a fine example of pre-war Crown Heights architecture, a building worthy of admiration. Most, if not all, of the museumgoers wouldn’t even give it an extra glance. But I do, every time I walk past, ever since I learned of the house’s history.

But if they knew the house’s history, they might. This townhouse, at 222 Brooklyn Avenue, was the stuff of nightmares. Where girls and women screamed for their lives and no one heard. Where a self-styled preacher with an ill-fitting toupee and a pencil-thin mustache driving a cream-colored Cadillac with its own bar and color television created a church that was more about his sinister desires than about the worship of God. And where, amazingly, many of his descendants still live, in communion with past—and perhaps present—horrors.

***

DeVernon LeGrand didn’t learn how to be a hustler all on his own, though the instincts were present early. Born in 1924 in Laurinberg, North Carolina, LeGrand moved to Manhattan at the age of twelve, and by the time he came of age his rap sheet was in full bloom. A 1946 arrest for failing to carry his draft card. A 1947 bust for attempted rape. A suspended sentence for arranging an abortion. These were mere prelude to further descents into depravity, dressed by day in flowing black robes, and by night in maroon jackets, ascot scarfs and gold trousers.

As LeGrand’s arrest record grew, he found an early calling hitching himself, professionally speaking, to other grifters. There was one Mother Robinson, for whom LeGrand worked as a chauffeur until her death in 1949. Then he moved on to a fake preacher named Daniel E. Davis, who had started up the “New Day Holy Church of God” at the tail end of World War II. LeGrand was a procurer of women, and his product included his first wife, Helen, and his sister, Sarah Moloney.

Their task: dress up as nuns, in black habits clutching tambourines to their bosoms, and solicit around Times Square, department stores like Macy’s and Straus’s, and subway stations from Harlem to Crown Heights. The women could keep all the cash save for $2.50 per day—eventually doubled to 5 bucks per—which kicked back to the “Church.” The racket cleared well over a hundred grand a year then, which would be close to a million dollars today.

The crime novelist Chester Himes had left New York City by the time DeVernon and Helen LeGrand, Sarah Moloney, and several others were arrested in 1953 for solicitation and fraud. (The women were convicted and given prison sentences of several months each; DeVernon was acquitted, continuing his pattern of beating charges.) But Himes described the scam so accurately in A Rage in Harlem that he must have witnessed the grift in action, or knew someone who had:

“No one paid her any special attention. There were many black Sisters of Mercy seen throughout Manhattan. They solicited in the big department-stores downtown, on Fifth Avenue, in the railroad stations, up and down 42nd Street and throughout Times Square. Only a few persons knew the name of the organization they belonged to. Most of the Harlem folk thought they were nuns, just the same as there were black, kinky-headed, frizzly-bearded rabbis seen about the street.”

One Sister of Mercy in particular merited her own description: “dressed in a long black gown similar to the vestments of a nun, with a white starched bonnet atop a fringe of gray hair. A large gold cross, attached to a black ribbon hung at her breast. She had a smooth-skinned, round black cherubic face, and two gold teeth in front which gleamed when she smiled.”

Himes was describing his own fake nun, a man dressed in women’s garb who would be the central driver of the plot before his series detective antiheroes, Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones, arrived on scene. But he could have been describing Helen LeGrand, who made sure—when her husband broke away from Davis and put out his own preaching shingle in 1956—that the bevy of fake nuns went out every day and returned with enough cash to cover the $5 a day kickback.

Whether Himes followed what happened next isn’t known. But if he had kept up with LeGrand’s shenanigans, he could have had yet more fodder for his Harlem Detectives, or a story too wild for even them to contend with.

***

DeVernon LeGrand moved his flock of women and children to 222 Brooklyn Avenue in the early 1960s. By that time LeGrand styled himself as a “Doctor and Physicologist, Metaphysics & Theology” hanging a sign over the door at the townhouse. He claimed to teach classes every Wednesday evening at 8:30. He advertised his ability to preside over weddings and funerals. “I have the power of divine healing,” LeGrand once declared. “I don’t charge no salary for this. I lay my hands on you and you recover. For that you give me a blessing.” In other words, a donation, often a hefty one.

It all sounded odd, but not necessarily sinister. There was a pending state investigation into whether St. John’s Church of Our Lord was a cover for fraud, dating back to 1961, but it had stalled out. There were rumors of raucous parties ending in fights as drunken men and women spilled out into the streets, but did that rise to the level of criminality? The neighborhood wasn’t sure.

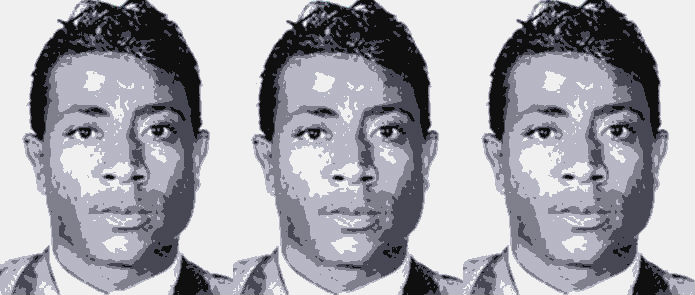

DeVernon LeGrand

DeVernon LeGrand

And as for those other rumors of young girls being picked up by LeGrand in his shiny Cadillac, promising them the moon, only to be taken back to the townhouse and threatened with beatings (or worse) if they didn’t adopt the fake nun grift, those seemed too fantastical to be real. They had to be.

Then the disappearances began to mount.

No one really cared until Brooklyn police raided the four-story townhouse at 8:30 on the morning of September 1, 1965. As detailed in a three-part series by Rana Gustaisis for the Philadelphia Daily News later that month, a team from the DA’s office stormed the house, search warrant in hand. “The first thing I saw were bare women running all over the place,” Detective Michael Lizzio told Gustaisis. Of the eleven women present that evening, seven were pregnant. Cops counted forty-seven children on the premises, too. Most every one of them bore some resemblance to LeGrand.

What interested police, though, were reports of three women who had gone missing, perhaps murdered, who had long been associated with LeGrand, and were last seen in 1963: Anne Sorise, Mary Horan, and Lulu King. Then there was Bernice Williams, very much alive, who claimed to have been held prisoner at the townhouse for a week without access to food. And Ernestine Timmons, who claimed LeGrand “assaulted her about the head and body with fists and a stick,” and Betty Jean Davis, who detailed how LeGrand threatened her with a gun in June 1964.

Police headed for the townhouse’s cellar and began to dig for remains. They found none, but did turn up stolen weapons, contraband marijuana, and enough charges to bust DeVernon for kidnapping Williams. “I heard a scream,” one neighbor recalled to Gustaisis. “A woman from the house ran down the block. [LeGrand] came after her and yelled, ‘Come back!’ She stopped dead, turned around, and came back. He slapped her and they went into the house together.”

Prosecutors were hopeful. They believed they had enough evidence to convict. But they didn’t. The charges evaporated. Witnesses clammed up, and there was talk of a coordinated campaign of intimidation. DeVernon LeGrand beat another rap, and it wouldn’t be the last he bested.

There was a 1968 rape charge, where the woman, Kathleen Kennedy, ended up as his next wife and mother of two of his children. There was the 1970 disappearance of Ernestine Timmons, the same woman who had accused LeGrand of assault several years before. Her irate father went to the Brooklyn Avenue townhouse to confront LeGrand, armed with a pistol. LeGrand took several bullets to his body, but he survived the onslaught. (Another member of the “church” did not.) Timmons remained missing, as did others.

If you were a young girl, black or white, riding in LeGrand’s tricked-out Cadillac, living at the Church…there was no predicting whether you would make it out of the premises alive.If you were a young girl, black or white, riding in LeGrand’s tricked-out Cadillac, living at the Church, or its satellite 58-acre estate in White Sulphur Springs, a Catskills area about a hundred miles north of the city, there was no predicting whether you would make it out of the premises alive. Neighbors of “LeGrand Acres,” as the Catskills estate was called, grew ever more suspicious of the sounds of gunfire, wailing children, shouting women, and trampled crops. They complained to state authorities to little result, leading to further rumors of crooked cops in LeGrand’s pocket.

Then DeVernon and his son Noconda were busted for the rape of a 17-year-old girl that happened at the townhouse on August 22, 1974. Would this charge, like so many other previous ones, evaporate into dust? Or would the Brooklyn DA’s office actually make it stick? It helped that they had a secret weapon: teenage sisters Gladys & Yvonne Rivera.

Gladys was married to another of the LeGrand offspring, Darryl Stewart. Yvonne was younger by two years. They, like so many, lodged at the townhouse. They heard the screams. They witnessed the horrors. And secretly, they began to plot a way out, which after months of pleading by their mother to leave, was a welcome sign. “He had them under his power,” Gladys and Yvonne’s mother later told the crime writer George Carpozi, Jr., who noted the quotes in his writeup for True Detective. “He was an evil man. I don’t know how he managed to hold them under his spell. I begged them to leave him but they wouldn’t listen…”

LeGrand and Noconda were convicted in February 1975 on the rape charge. LeGrand then stood trial for bribery that September. Gladys and Yvonne testified, and the preacher was found guilty. They were due to testify the following month in a different rape case. LeGrand remained in prison while awaiting trial, and prosecutors hoped that witnesses would be a lot less reluctant to testify than they had been in the past.

There was a problem: by October 1975, the Rivera sisters had vanished.

1975 gave way to 1976. Brooklyn investigators were pretty certain of Gladys Stewart and Yvonne Rivera’s fate—they had a surprise witness show up in November to say so—but it was a question of whether they had perished in their jurisdiction or if it was something for Sullivan County. Early in March, a team of diggers went to White Sulphur Springs with picks and shovels. When the days of digging once more turned up empty, the divers went to work. And on March 6, deep in the water by LeGrand Acres, investigators found what they sought.

***

When DeVernon LeGrand was indicted for murder on March 12, 1976, the Brooklyn district attorney, Eugene Gold, was as confident as he could be that the preacher would really, truly spend the rest of his life in prison. The surprise witness? LeGrand’s wife, Kathleen, forced to marry him seven years earlier to make the rape charge go away. “My husband killed them,” she told stunned detectives, then explained that the caretaker, Frank Holman, “knows much more than I do. He helped get rid of the bodies.”

Kathleen continued. “The girls….they were cut up after they were killed and…well, you talk to Frankie…he knows what happened.” They did talk to Frankie. And Holman, who turned to the church after working several years as an assistant in the Brooklyn Medical Examiner’s Office, went far further in his graphic descriptions of what happened to Cheryl and Gladys.

There was an argument, when LeGrand learned on the night of October 3 that the girls had turned state’s witness. “That bitch is complaining too much,” LeGrand told Holman. “I’m going to take care of her right now and end all this bullshit…” He trailed off, before telling Holman to convene about sixty members of the Church to the house. They wouldn’t be allowed to leave for hours. Holman had to make sure of it. “While I was watching so that nobody left,” he told investigators, “I heard the screams of a woman.” Holman led the terrified, imprisoned parishioners in a hymn “to keep them from panicking.”

Then one of LeGrand’s many daughters burst into the church’s front room. “Daddy’s stepping all over Gladys,” she shouted. The hostages wouldn’t be able to leave until 2:30 in the morning, when LeGrand gave the most morbid of all-clears.

Holman’s task was even more lurid. LeGrand needed him to transport “two garbage cans in the backyard with the covers on” up to White Sulphur Springs. Holman protested: “Can’t this wait till the morning?”

“No, get your ass moving right now.”

Holman knew enough not to protest. He knew what kind of man LeGrand was. As Kathleen later told investigators, going against her husband resulted in major trouble. “Let me tell you something,” she heard him shout to one of his other daughters, “You all remember Gladys. Daughter or no daughter, you’ll join the bitch. You know what I do with bitches. I burn them.”

“While I was watching so that nobody left,” he told investigators, “I heard the screams of a woman.” Holman led the terrified, imprisoned parishioners in a hymn “to keep them from panicking.”Holman loaded the garbage cans, as well as a box stuffed with women’s clothing, into a Ford station wagon. Whey they arrived at LeGrand Acres, Holman said, “DeVernon told me to fill an old bathtub with benzene and empty what was in the garbage cans into the tub, which was outdoors and near the barn.” What he found in the cans were “large plastic bags filled with body parts,” including what he believed to be Yvonne Rivera’s head. Based on his prior expertise, Holman believed the girls were dissected “with a sharp knife” followed by “an ax, a cleaver, a large knife, or a saw.”

Then the parts were set on fire, burning for hours in a large stone barbecue pit behind the main house. LeGrand ordered Holman to “dump the ashes and other remains into the lake.” Holman did as the preacher wanted. He also never forgot one other thing LeGrand said: “That little bitch (Yvonne) came down to see about her sister, and I got her, too.”

Kathleen LeGrand and Frank Holman’s statements, in tandem with the remains found at LeGrand Acres, and other disturbing material recovered from the townhouse—including two hacksaws, three bloodstained bedsheets, a .22 caliber rifle, eleven shells, and a pair of scissors—bolstered the state’s case against DeVernon and his son, Steven. Both were convicted almost a year later, on March 6, 1977. The Daily News reported neither man showed much emotion at the verdict.

***

The Brooklyn district attorney, Michael Gold, got his wish. DeVernon LeGrand died at Green Haven Correctional Facility in 2006, age 82. Five years earlier, at a hearing where his parole was denied, the commissioners concluded: “Your conduct indicates a depraved indifference for human life and no respect for the law.”

How much of a depraved indifference for human life is still not fully known. When LeGrand was convicted for murdering Gladys and Yvonne Rivera, Gold believed the fake preacher was responsible for the murders of as many as 20 girls and women. Ann Sorise and Ernestine Timmons seemed likely victims. So, too, did Elizabeth Brown, a fifteen-year-old girl picked up by LeGrand at a College Point, Queens amusement park in 1974, drafted into the sordid fake nun life through sex and drugs, and never seen again after 1977.

And several other LeGrand sons, including Steven, were convicted in 1978 of the murders of Jeffrey Miranda and Howard Tippins four years before, in what appeared to be a revenge killing for having “kidnapped, raped, and held for ransom a prostitute belonging to the LeGrand stable,” according to the Daily News.

Every few years, law enforcement descends upon 222 Brooklyn Avenue looking for answers. Sometimes it’s in response to rumors of buried dead bodies. Other times it’s to check why the so-called Church never stopped operating, now under the name of St. Joseph’s Church of Christ and Home. Current LeGrand family members have insisted to the papers that their work is above-board. They settled with the city over several house raids in 2016. The sins of DeVernon should not necessarily cast aspersions on the next generation, who just want to live their lives in private peace.

But the “church” is reportedly being run by Noconda LeGrand, who also served time for rape. And as recently as 2010, his sister, Mindy, was reported to be soliciting in a subway station—doing the exact fake nun scam that was her father’s bread-and-butter six decades before. She later claimed she was collecting funds “to pay back taxes.”

***

One summer afternoon, I found myself walking down Brooklyn Avenue, past the Children’s Museum, across the street from the LeGrand townhouse. I took out my phone and snapped some photos of the exterior from what I felt was a safe enough distance. Two men stood on the townhouse stoop. They glanced at me, mid-shot. Their expressions made clear what I already sensed: I should not cross the street. I should not go over and talk to them.

But it’s another year, and another summer. I know I’ll find myself on that stretch of Crown Heights again. This time, there may be no one outside 222 Brooklyn Avenue. This time, I might cross the street. Walk up the steps. Rap on the door.

And if I do, and it opens, will I go in?

—Original art by Joe Gough