My first novel The Bloodless Boy includes dozens of real people from history, both the famous and the infamous, placing them in a fictional setting. The time and place in which the action takes place—late 1670s London—was full of larger-than-life characters. Here, I profile ten ‘rogues’ of the time, some of whom appear in The Bloodless Boy, and some in the sequels I have written.

Charles II 1630—1685

At the time of The Bloodless Boy, Charles has just prorogued Parliament, seeking to rule without it. This provoked fear that he wanted to rule absolutely, like his father Charles I. A genuine fear (along with the fear caused by the Popish Plot) was that there would be another Civil War, as the relationship between Court and Parliament was so strained. I call him a rogue not only because of his many mistresses and fourteen acknowledged illegitimate children, or that he was known as ‘the merry monarch’ and ‘Old Rowly’. He also had a way with pardoning the unlikeliest of people, perhaps because of political expediency, sometimes because their audacity pleased him.

I find him an endlessly fascinating character: complex, cunning, known to have the ‘common touch’. He was toughened by his father’s execution, his soldiering, and his experience of exile after the Civil Wars. He was a brave and competent commander. He led the effort to fight the Great Fire of London. Also, he gave the Royal Society its seal, having a keen interest in its experiments and his own ‘elaboratory’ in Whitehall Palace.

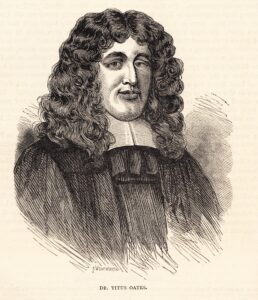

Titus Oates 1649–1705

Serial liar, fantasist, and perjurer, Oates fabricated evidence (his ‘Articles’) of a Catholic uprising to assassinate the King and take over the government. His false testimony led to the executions of fifteen innocent men. King Charles II never believed Oates, but passed the matter to others who were more credulous. (Perhaps it suited them to be so.) The hysteria inspired by Oates’s Articles, along with the murder of a Justice, Sir Edmund Bury Godfrey, led to anti-Catholic violence. Even to be dubious, or moderate, was to risk being viewed as treasonous. Oates enjoyed seven years of fame, popularity, and a State pension, including an apartment at Whitehall. It was not until James II succeeded his brother that Oates was put on trial for perjury. He was sentenced to prison and to be ‘whipped through the streets of London five days a year for the rest of his life.’

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury 1621—1683

At various times in his political career, Shaftesbury was Chancellor of the Exchequer, Lord Chancellor, then First Lord of Trade. He was imprisoned for a year in the Tower of London when he spoke out against the King’s increasing antipathy towards Parliament and his desire to rule without it, and also for his view that the King’s Catholic brother, James, should be barred from inheriting the throne. Shaftesbury led the Country Party, who sought to constrain the powers of the Court, seeing it as corrupt. It eventually became known as the Whig Party. Shaftesbury’s supporters called themselves the ‘Green Ribbon Club’. They weren’t averse to using threats and violence to encourage support for their cause. What makes Shaftesbury a rogue, rather than merely a political adversary to the King, is his role in the Popish Plot: there’s no doubt he sought to profit from it, but how closely he was involved is open to interpretation. I suspect much letter burning was done. His secretary was John Locke, later famous for his philosophy. He must have known a few secrets about the conspiracy against the King.

Hortense Mancini, Duchesse De Mazarin 1646—1699

One of five sisters famous for their beauty. A niece of Cardinal Mazarin, the chief minister of France. When Charles II proposed marriage to her before his Restoration, Hortense turned him down, as he was too poor. Instead, she married one of the richest men in Europe, whose jealousy and extreme prudishness (he insisted his female servants’ front teeth were removed to lessen male attention) made her miserable. Escaping to London, she became one of Charles II’s mistresses, but also had an affair with his daughter Anne Lennard. and with the novelist and playwright Aphra Behn. Hortense enjoyed cross-dressing, gambling, and drinking. She has a brief appearance in The Bloodless Boy, but so enamoured am I, I wrote a much larger role for her in the sequel.

Thomas Blood 1618—1680

A Parliamentarian in the Civil War (having swapped sides from the Royalists when he saw how the war was going), Blood had his Irish estate confiscated after Charles II’s restoration. In 1671, he decided to steal the Crown Jewels from the Tower of London.

Disguised as a parson, he befriended the Keeper of the Jewels, Talbot Edwards, with an accomplice pretending to be his wife. They became so friendly, they even arranged Edwards’ daughter meeting the parson’s wealthy nephew. When the ‘nephew’ arrived, they asked to see the jewels. After opening the grill which protected the jewels, they knocked Edwards on the head. Blood flattened the crown with a mallet and stuffed the orb down his trousers. Blood’s brother-in-law (a man named Hunt, but no relation to Harry Hunt, as far as I know) tried to saw the sceptre in half, but Edwards regained consciousness and alerted the guards. Dropping the sceptre, Blood and his men ran. Despite shooting at one of the guards, they were arrested.

Blood declared he would answer ‘to none but the King himself.’ He got his wish: King Charles II, Prince Rupert, and the Duke of York questioned him. When the King asked, ‘What if I should give you your life?’ Blood supposedly replied, ‘I would endeavour to deserve it, Sire!’ Charles pardoned him, and gifted land in Ireland worth £500 a year. But what had Blood done to gain the King’s pardon? One theory is that Blood served the King as a secret agent, and this was his reward.

Eleanor Gwyn 1650—1687

Nell Gwyn was an actress, and mistress of Charles II, producing two sons by him. Brought up in her mother’s bawdyhouse in Covent Garden, at the age of about twelve, she became an ‘orange girl’ in the Drury Lane Theatre. She then rose to the role of actress. Pepys described her as ‘Pretty, witty Nell’.

In 1681, at the time of the Popish Plot, she was inside a coach when she was mobbed, the angry crowd mistaking her for the unpopular Duchess of Portsmouth, another of the King’s mistresses and a Catholic. Nell reassured them by telling them, ‘Pray good people be silent, I am the Protestant whore.’

Jack Ketch ?—1686

‘The jury brought him in guilty, and Jack Ketch will make him free.’

Although Jack Ketch wasn’t the only executioner in London at the time, he was the most (in)famous. An executioner for 23 years, from 1663 to 1686, his name became slang for any executioner, death, and even Satan. ‘Jack Ketch’s Kitchen’ was a name given to a room where they boiled the limbs of those quartered for treason. A noose was ‘Jack Ketch’s Necklace’.

Following the executions of Lord Russell and the Duke of Monmouth, he was accused of accepting bribes to make them suffer. (Although both men had also paid Ketch to be merciful.) During Monmouth’s beheading, Ketch struck him five times. Monmouth is said to have got up and remonstrated with him halfway through. In the end, Ketch had to remove the Duke’s head with a knife. To avoid being lynched by the outraged crowd, he had to leave surrounded by soldiers.

Samuel Pepys 1633—1703

Important Navy administrator, a Fellow—and for a while, President—of the Royal Society, and an accomplished musician. He was also a voyeur and rapist. His diary details many ‘extramarital liaisons’, often in a multilingual code: ‘… there did what je voudrais avec her, both devante and backward, which is also muy bon plazer.’

Some of these episodes, it seems, were consensual, although you have to remember the evidence was written by him. He seems quite frank about those that weren’t, though, so I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt. One distasteful diary entry, from February 1663 reads, ‘This night late coming in my coach, coming up Ludgate Hill, I saw two gallants and their footmen taking a pretty wench, which I have much eyed … a seller of riband and gloves. They seek to drag her by some force, but the wench went, and I believe had her turn served, but, God forgive me! what thoughts and wishes I had of being in their place.’

Pepys’s wife Elizabeth caught him with Deborah Willet, who was employed as her companion. Elizabeth ‘did find me imbracing the girl con my hand sub su coats; and endeed I was with my main in her cunny. I was at a wonderful loss upon it and the girl also …’

His diary shows him often berating himself before God for his thoughts and behaviour. He purchased a book called L’Escole des Filles, a ‘mighty lewd book’, and after reading it, he burned it.

Captain Jeffrey Hudson 1619—1682

As a child, Hudson was presented to Queen Henrietta Maria at a banquet, served to her inside a pie. He emerged from the pastry wearing a miniature suit of armour. He was esteemed at Court for his extremely small stature (18” tall or so) and for being ‘exquisitely’ proportioned. Despite his size, Hudson was a good horseman, and an excellent shot. During the Civil War, Henrietta Maria made him a Captain of Horse. Looking for funding from the French to equip her husband’s army, she took Hudson to Paris with her, but when he was there, he killed Charles Croft, the brother of the Queen’s Master of Horse, in a duel. Croft underestimated him, and insulted him by turning up to the duel with a ‘water squirt’. Hudson shot him through his heart. The French expelled him. On his journey back, Hudson was captured by Barbary pirates, and spent 25 years as a slave in North Africa, before being ransomed back to England. Strangely, during his captivity, he grew considerably in size, an odd fact I make much of in the sequel to The Bloodless Boy.

Karl Johannes Königsmark 1659—1686

In the Hague, newly married Elizabeth Thynne (née Percy, one of the richest families in the country) met Karl Johannes Königsmark, a Swedish Count. With dashing good looks and blond hair down to his waist, Elizabeth soon enjoyed his company more than her husband’s. Through his steward, Captain Christopher Vratz, Königsmark issued Thomas Thynne (the husband) a challenge to a duel. Thomas declined, instead sending a group of his men to murder Königsmark. Königsmark escaped them.

He and Vratz travelled to London. With a Pole named George Boroski, and Swedish mercenary John Stern, they intercepted Thomas Thynne’s carriage along Pall Mall one evening, and Boroski fired his musquetoon into the carriage.

Thynne, wounded in four places, died the following morning, surrounded by the Duke of Monmouth and his friends.

Sir John Reresby quickly found Vratz, Boroski, and Stern. A week later, the Duke of Monmouth’s steward tracked down and arrested Königsmark at Gravesen, and brought him back to London. Vratz, Stern, and Boroski were charged with murder, but Königsmark was acquitted. John Evelyn, in his diary, said he ‘was acquitted by a corrupt jury’. Again, the influence of Charles II is suspected, not least because Thynne was a great friend of Monmouth, his illegitimate but popular Protestant son, who many wanted to succeed to the throne instead of the Catholic Duke of York.

***