One morning, not long after my first novel, Finding Jake, was published, I walked my kids to the bus stop. As I stood just outside a pod of my neighbors, watching our kids roll away, one of the dads stepped up to me. Understand, the exchange was nothing but friendly. Conversational, even. But it was the beginning.

“We really enjoyed your book,” he said.

“Thanks,” I said, my eyes lowering, a little embarrassed by the attention.

“Yeah,” he said, staring at me. “It was really cool to read a story with so many familiar details.”

I didn’t get it at first. Social interactions have always confused me to some degree. The nuances lost until I have time to think about it. When he continued, I picked up my first hint.

“My wife really found it… interesting.”

I slipped out of the conversation and went home. Later that day, I ran into another neighbor as we walked our dogs. I saw the hunger in her eyes as she approached.

“(Name withheld for my own safety) is mad at you,” she said.

She was talking about the wife of the man I had spoken to that morning. I had a sense of where this was going, but I had to ask.

“Why?”

“What you wrote in your book about her,” she said.

I took the time to explain myself, knowing this conversation would get back to her. Regardless, we didn’t get their Christmas card that year, or any year since….

Writing books is truly a great job. The commute is nonexistent. The schedule is fairly flexible. The physical strain is no worse than a bout of carpal tunnel syndrome. But there is a dark side. A very true and personal danger. One someone should have put in the job description. An occupational hazard that should come with a warning label. When you write dark stories, particularly one about a serial killer, people certainly start looking at you a little differently.

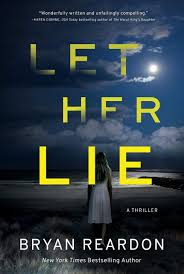

Just for background, here are the topics covered in each of my four published novels—a school shooting, domestic terrorism, alcoholism and abuse, and my newest book due out in February, Let Her Lie, a serial killer. If you lived next door to me and you read any of the four, you might give me the side-eye. You might install a camera outside your house, surreptitiously pointed in my direction. You might not invite me into the carpool for our daughters’ dance class. And, I guess, I can’t blame you.

The question is simple. How can a normal person come up with stuff like that? If they can, they must think about it. And if they think about it, how far is that from actually dabbling, really? Right? Sometimes I imagine my neighbors practicing the interview they will give to the local news station when the truth comes out. When I’m finally caught.

Maybe that would make a good book. The author next door acting out his darkest fantasies. Like a domestic Basic Instinct. But it’s just not believable. I’m pretty much a softy. I don’t like setting mouse traps. If I accidentally walk out of the grocery store and notice I have something under the cart that I forgot to pay for, I head back in. I even hold doors for the elderly, as hard as that may be to believe.

So how did this happen? Why do people I know come up to me with a sheepish laugh and ask how I come up with such dark ideas? How did I scare all of the people around me? It’s simple. Just as people see me in my stories, they see themselves in my characters. If I’m writing about real people, I can’t be making up everything else, right?

I’ve provided this exact explanation so many times. To my mom after she got upset with me because of the father character in my novel, The Perfect Plan. To my son’s teacher after the cover of Finding Jake came out looking eerily like him. And at almost every festival or event I’ve attended when an audience member comments on my newest book being a little more “disturbing” than my last. The short answer is, I make it all up.

In reality, this misunderstanding, in my opinion, all comes down to the conception of a character. My life is pretty boring. Certainly not something that would make a plot for a novel. And, I apologize in advance, the people in my life aren’t much more thrilling. But I do something that causes this confusion. When I start a book, I have a character in mind. This person is utterly and completely fictional. This person has to do some crazy things, survive life and death situations, to get to the end of the story. Like I said, this person is absolutely no one I know.

Then I start writing. It is the little details that pop up. I might set a scene at someone’s house, even. Or my character might find his/her self in a real-life situation. These mundane moments anchor a story. Give it a sense of reality. And I blatantly steal them from my real life. In my first book, I included a play date that pretty much happened. In my most recent book, my main character struggles with a sense of purpose that might be my own. These descriptions, or actions, or settings cause most of my agita. For those around me recognize them. And when they do, they identify with that character. They think I wrote them into the story. But I’ve never done that. Every character I’ve written is their own person. And no character I’ve written has a single person as their basis.

Back to the story that began this discussion. What, you might ask, made my neighbor think I wrote about her? What made her so angry that she has yet to forgive me? It’s a delicate answer, but I’ll do my best. In my first book, one of the main character’s neighbors has a physical attribute. Or, more specifically, an augmented physical attribute. From what I’ve come to understand, my neighbor has a similar… augmentation. A fact that I was blissfully unaware of until that fateful day. And the absolute truth, though I’ve tried not to say it for fear of offending her or anyone, I never thought of her once while writing that book.

So, to that neighbor, and to all those that I’ve frightened, let me leave you with one plea. Please consider that the imagination we try to cultivate and grow in our children might well be alive in some adults. They are, after all, just stories. Stories that I hope prompt a discussion about the state of society and culture.

*