What do the following have in common: rituals shrouded in mystery; a closed circle of suspects; backstabbing intelligentsia; built-in power structures; and beautiful settings, from the gothic to the bucolic. They could be features of many crime novels, no matter the genre, but they’re also some of the reasons why academia has proven such a rich source for crime fiction. Here are six standouts (five novels and one true crime).

Gaudy Night, Dorothy L. Sayers (1935)

I teach a course called Women Crime Writers as part of the Emerson College MFA program. Sayers’ novel was the first book I added to the syllabus (paired with her fantastic essay, “Are Women Human?”). Set in Oxford’s Shrewsbury College, the novel focuses on Lord Peter Wimsey’s occasional partner, Harriet Vane, who returns to attend a gaudy (a reunion of sorts) expecting to be called out for having been accused of murder (in 1930’s Strong Poison). Instead, Harriet has a blast – and snarks on plenty of her fellow alums herself – only to have the event marred by a series of malicious pranks, including a poison pen letter, graffiti, and vandalism. Harriet then calls on Wimsey to solve the crime.

This is by far my favorite of Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey novels, if only because it’s more of a Harriet Vane novel, and she’s a much more interesting character for me. It’s too bad that Sayers abandoned the series after one more book (1937’s Busman’s Honeymoon). Who knows what Harriet could have done if she’d been given her own novel?

The Matlock Paper, by Robert Ludlum (1973)

This early Ludlum thriller has many of the trademarks of his better-known novels—a solitary hero takes on a mysterious figure as he tries to bring down a massive crime organization. I love it because the hero is a professor at Connecticut’s Carlyle University, a stand-in for Ludlum’s (and my own) alma mater, Wesleyan University.

The Secret History, by Donna Tartt (1992)

How can you write about academic novels without bringing in Tartt’s terrific debut? Set at the fictional Hampden College in Vermont (and based on Tartt’s very real alma mater, Bennington College), the novel follows a group of six academically gifted classics students who— no spoilers because happens in the first pages—kill one of their own. The novel follows the build up to and the aftermath from the crime and its lasting impact on those who survive. Reading the novel for the first time in a decade or so, I’m stunned by its intelligence, and how Tartt succeeds in creating richly drawn characters who are intelligent, annoyingly intelligent, and annoying, sometimes in the same paragraph. More than any other novel on this list, it makes me yearn for my own college days.

The Widows of Malabar Hill, by Sujata Massey (2018)

Set in colonial India in the early 1920s, this novel follows Perveen Mistry, an Oxford-educated lawyer dedicated to women’s rights. I often assign this novel in my MFA courses too, not only because Massey is a terrific writer who’s created a fantastic protagonist, but also because the novel is an excellent example of how to use time in character and story development. The novel takes place in 1921, with significant flashbacks to 1916 when Perveen was much younger and more naïve.

Technically, this isn’t a novel of academia, if only because Perveen leaves Bombay and attends Oxford during the years between the two main storylines, yet those years away infuse the story, and give Perveen the time and space to develop into a woman willing to offer a voice to those who might not have one otherwise.

The Truants, Kate Weinberg (2020)

The set-up for this novel is straightforward: intellectually curious Jess escapes her middle-class home when she discovers a book of literary criticism called The Truants by Dr. Lorna Clay. She enrolls in a third-tier university in east Anglia where everything is gray, from the buildings to the sky, to study with Dr. Clay, and soon finds herself part of a sexually entangled foursome. At first, the novel reads like equal parts Muriel Spark – the charismatic and controlling teacher who blurs the lines between professional and personal—and Donna Tartt—intelligent, annoyingly intelligent, and annoying students—but about two thirds of the way though, it takes a turn to the unexpected. Much like Jean Brodie’s girls in Spark’s The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, Jess is a sponge ready to absorb personalities and ultimately test boundaries. The fun of this novel – as much a coming-of-age novel as a mystery – is learning who Jess decides to be.

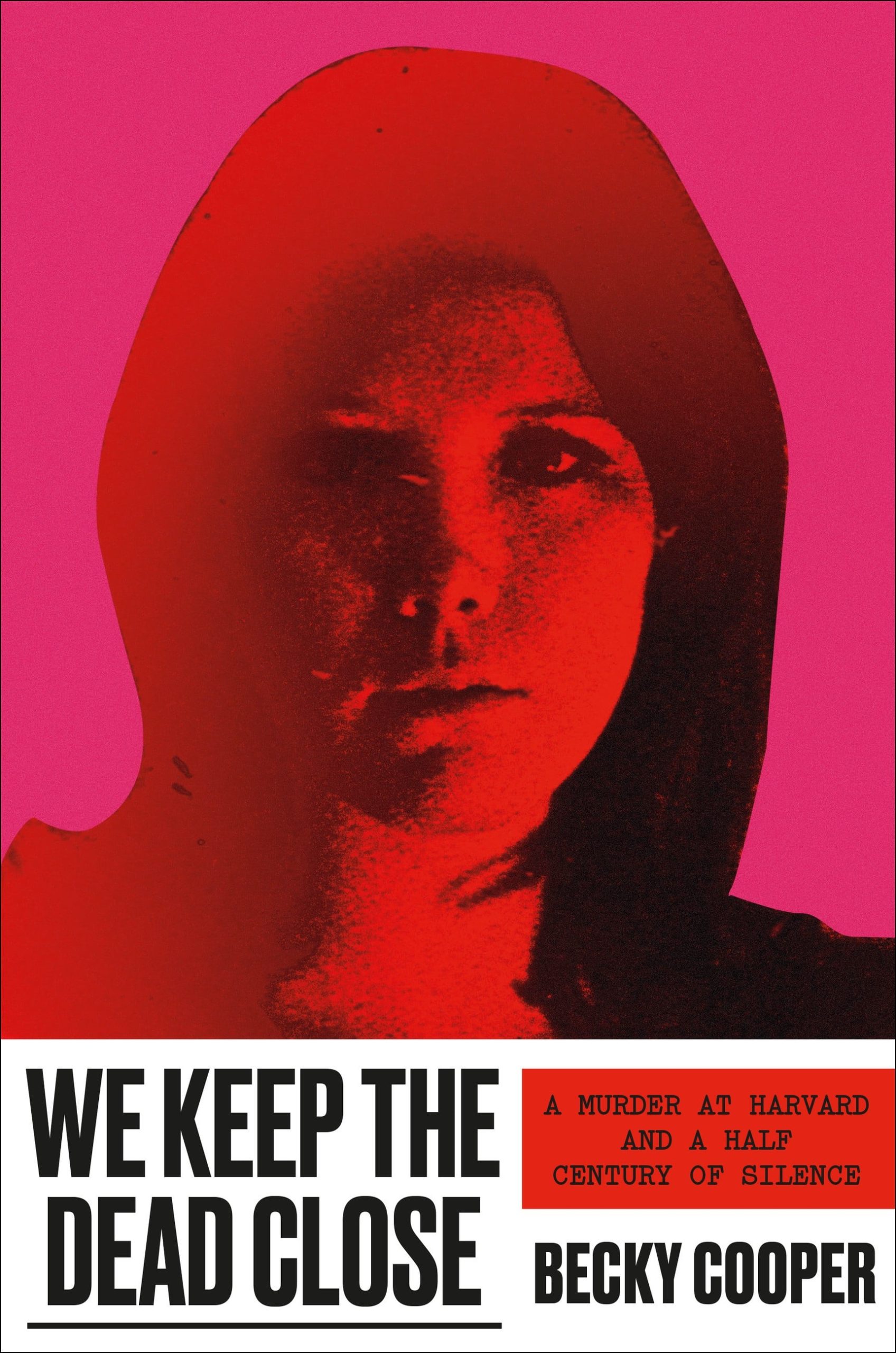

We Keep the Dead Close, Becky Cooper (2020)

Jane Britton, a graduate student in Harvard’s anthropology department, was brutally murdered in the winter 1969. Cooper heard rumors of the murder as a Harvard undergraduate and eventually became obsessed with finding out what really happened to Britton. The narrative alternates between telling Britton’s story, and Cooper’s investigation, and the answer is a stunner.

My series is set in Boston and the main character, Hester Thursby, is a research librarian at Harvard’s Widener Library. Maybe in a future novel, I’ll have Hester partner with an intrepid undergrad ready to solve a fifty-year-old crime.