They were the all-American couple and their town had been called the typical small American city. The daughter of a doctor and the son of a factory owner, they went to the privileged high school on the rich side of town. Their futures were bright.

But the September 1985 murders of Kimberly Dowell, 15, and Ethan Dixon, 16, ended the promise of high school graduation, college years and long, fulfilling lives. And their murders left a mark on the city of Muncie, Indiana: bereft parents, saddened classmates, frustrated investigators.

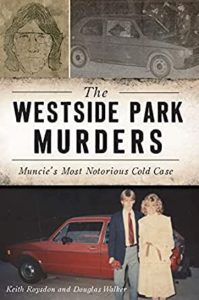

In 1997, my frequent co-author, Douglas Walker, and I first wrote, for The Star Press newspaper where we were reporters, about the tragic deaths of the couple. We wrote about Kimberly and Ethan many times after that, culminating in the February 2021 publication of our third true crime book for History Press, The Westside Park Murders: Muncie’s Most Notorious Cold Case.

The killings have become a horrible part of our city’s identity.

The city of Muncie, the subject of the 1929 sociological study, “Middletown in Transition: A Study in Cultural Conflicts,” had achieved a kind of cultural notoriety long before September 28, 1985. The city became a place national news organizations sent reporters to “take the temperature” of the country. Reporters questioned Muncie’s citizens, who ranged from the elite of the Ball State University community to the southside blue-collar workers who toiled, by the thousands, in the city’s factories.

Muncie was already a regular presence in pop culture, from references in cartoons like “Tom Slick” to the opening scenes of “Close Encounters of the Third Kind”—Richard Dreyfuss wore a “Ball U” T-shirt in the movie—to many movie and TV shout outs over the decades that followed. The characters of “Parks and Recreation” couldn’t understand why office pariah Jerry had a time-share in Muncie.

But aside from those references and other cultural touchstones—David Letterman went to Ball State and Jim Davis, the creator of Garfield, had a studio outside of town—Muncie was best known as a city where unpunished lawlessness was the norm rather than the oddity.

“Muncie had a reputation of being a place where you could kill a man and get away with it,” a prosecutor told a jury in a 1965 trial. He was imploring the jury to convict the defendant in one of several murder cases ongoing at the time.

Muncie’s citizens were well accustomed to political corruption, with mayors and sheriffs arrested on state and federal charges several times over the years. It’s an ugly tradition that has continued for the better part of a hundred years; The most recent of those arrests came in 2019.

Murders have been ongoing too.

For most of a decade, Walker and I wrote, for The Star Press newspaper, a recurring series of articles called “Cold Case Muncie.” Between 2010 and 2018, we reported on 34 unsolved murders in Muncie, some dating back to the 1960s.

The first was the Westside Park case, which was a natural place to start because it was so well remembered.

Ethan and Kimberly had been shot to death in Westside Park shortly before midnight on a Saturday night. Their bodies, in the front seats of Ethan’s Volkswagen Rabbit hatchback, were discovered by a police officer who was so startled to see what his flashlight beam revealed inside the car that he momentarily turned off the light and stood in the darkness before radioing for help.

Word spread quickly, even in those days before cell phones and social media. By the time a headline appeared in the next morning’s newspaper, phones – on the walls of family kitchens and in teenagers’ bedrooms – were ringing as Ethan and Kimberly’s classmates shared the tragic news and grieved.

In the weeks that followed, police telephones were flooded with tips and hundreds of suspects and theories—including that the killings came about as a result of a Dungeons and Dragons game gone horribly wrong—were checked out and dismissed. Rumors filled the void when police had no progress they could announce.

And the case grew cold.

In many cold cases that we wrote about, no newspaper articles had been written since the initial story recounting the murder. In those cases, the victims were people who had been forgotten by everyone but their families and a few longtime cops. Both cops and survivors were haunted by the lack of closure.

In some cases, the unsolved murders had been forgotten by authorities because they had passed out of living memory and because police records had a tendency to become lost to flooded storage rooms, files misplaced when offices were moved … or just neglect.

Many of our Cold Case articles for The Star Press came about because one of us remembered a particular case, or a family member called the newspaper to ask us to do a story or a veteran investigator brought it up to us.

One of the oddest ways we found unsolved murders was to look through the newspaper library’s physical files of newspaper clippings, some dating back to the mid-20th century. Because the librarians included in each manila envelope clippings from the trials of suspects arrested in the crimes, we zeroed in on the thinnest murder files, realizing it was likely that a criminal charge had never been filed and a suspect had never been tried. In other words, a cold case.

The newspaper files for Dixon and Dowell were thick, however, mostly because of “no new leads” updates from the police on anniversaries of the killings. Fewer articles appeared as time went on.

That first article Walker and I wrote, in 1997 on the 12th anniversary of the killings, was an in-depth look at the case and included the first public comments from Kimberly’s stepfather, a Ball State official who had long been spoken of, in hushed tones, as a likely suspect in the killings. He talked about how the suspicion had ruined his life.

Over the next few years, we continued to push police investigators for news and published regular updates. In 2010, on the 25th anniversary of the killings, we recapped the case and interviewed Kimberly’s father, a physician.

It was the practice of Muncie police officials to ask an up-and-coming investigator to review the boxes and boxes of reports and evidence in the case. We got a sense from the latest of these investigators that he was developing a primary person of interest in the case.

By 2018, investigators went to court to get a DNA sample from a person of interest, who was in prison for another murder.

We were ready to go to work.

When our second true crime book was published in 2018, Kimberly’s father, the doctor, was the first in line to get our book signed.

When we interviewed him for the 2010 newspaper article, he had been as philosophical and as much at peace as anyone who has had a child taken from them by an act of violence could possibly be. He pointed to how the community was brought together in the wake of his daughter’s death and how he could draw some kind of peace from that.

We asked for, and received, his blessing for us to work on a book. He loaned us family photos of Kimberly and shared his memories.

In 2019, we spoke with Ethan’s father twice, once in the spring and once in the fall. If my son was taken from me, I would like to think I’d be as at peace as Kimberly’s father, but I think it’s more likely I’d be haunted and tortured like Ethan’s father seemed to be. He and his wife declined to be interviewed for the book.

Over the course of several months, we interviewed former police officers and prosecutors and recent investigators, studied autopsy reports and newspaper accounts from the time and talked with Ethan and Kimberly’s friends.

The interviews led us to discover facets of the case that we never knew and had never been reported. Many of them pointed toward modern-day police investigators’ primary person of interest, while others indicated wildly divergent avenues of investigation.

We wrote about what our city was like in 1985, what kids like Kimberly and Ethan liked to do—see movies and hang out, mostly—and looked at what a prosecutor from the time called a veritable flood of other, unrelated murder cases.

Someone asked me in a recent interview if I thought our book could bring a sense of closure for family and friends of Ethan and Kimberly, as well as for the two of us as writers and for members of the community as readers.

I’m not sure closure for some tragedies is possible, even when a resolution can be found. Some questions might be answered, but can anything bring closure for a loss like this?

*