TRIAL, DAY 9

Noah waited alone in the bull pen, a secured detention area of room-like cells on the bottom floor of the courthouse. The jury had been deliberating for two days, and it was eating him alive. Thomas had assumed the deliberations would take a day at most and hung with him from time to time, which Noah appreciated, not knowing how much longer he’d be in civilized company. Maybe not for the rest of his life. If he got convicted, he wasn’t going back to the smooth time at Montgomery County Correctional Facility. He’d be doing hard time in a maximum-security facility like Graterford. Assuming he didn’t get the death penalty.

He had to be hopeful. He didn’t know which way the jury would go. They could find him innocent.Noah tried not to think about that now. He had to be hopeful. He didn’t know which way the jury would go. They could find him innocent. It happened. People walked every day. He couldn’t control what the jury did, so he was trying to get to a place of acceptance, a favorite phrase from the overworked MSW at the jail, who did med checks and ran group therapy sessions. Noah had been given a coping toolkit to help him come to a place of acceptance. Problem was, the tools weren’t working now.

Suddenly the door opened, and a deputy admitted Thomas, filling the small room with his massive frame. He was six-foot-five and built like the linebacker he used to be at Cheney, and his presence and personality commanded attention in any courtroom. Right now his big features—round eyes, large nose, and oversized grin—were alive with animation, and he clapped his meaty hands together. “Great news, dude!”

“What?” Noah shifted on the metal bench, bolted to the wall.

“Lovely Linda is very nervous. Ask me why. Answer? Because I crushed that closing.” Thomas grinned broadly, his chest expanding, and he opened his arms to reveal a wingspan that strained the seams of his tailored charcoal suit.

“What’s up?” Noah felt a tingle of hope. Lovely Linda was what Thomas called the Assistant District Attorney, Linda Swain-Pettit. Thomas had nicknames for everybody in the courtroom, including the jurors.

“She’s worried the jury’s been out this long. She wants to make a deal.”

“No deal. I said already.” Noah didn’t know what he’d expected. The cavalry?

“No, this time, you’ll listen. I got her to sweeten the pot.” Thomas sat down next to him. His grin vanished, and he turned to Noah, his eyes narrowing with intensity, like a microscope focusing.

“No deal.”

“Wait.” Thomas held up his palm. “You’re charged with murder of the first degree. You’re looking at life without, or death. That’s possible.”

“I know that.” Noah had gotten used to the lingo. Life without meant life without possibility of parole, or LWOP.

“But if you plead guilty to third-degree murder, she’s offering twenty years.”

“No.”

Thomas’s eyes flared in disbelief. “Noah. I got her down from forty years, the max.”

“No.” Noah didn’t even have to think about it. He knew how he felt.

“Noah, you’re not listening. Sure, I gave a great closing, but don’t lose your damn mind. The fact that they’re still out doesn’t mean they’re going your way. Maybe somebody doesn’t want to go back to work. It’s snowing, maybe somebody doesn’t want to go home and shovel. You don’t know. You can’t risk it. Take the deal.”

“No.”

“She destroyed you on the stand. It was like watching a majorleague hitter swing at your head. I couldn’t believe you even stood up after that. I wanted to send you a stretcher.”

“Still, no.” Noah had underestimated how hard it would be to be cross-examined by an experienced prosecutor. He’d thought he could just tell his story.

“It’s like you have a death wish. Do you have a death wish, Noah?”

“No,” Noah answered, but the truth was yes, or at least, maybe.

“Noah.” Thomas took a deep breath, inflating his barrel chest, trying to calm himself down. “I’m begging you to take this deal.”

“I can’t.”

“Why not? Because of the plea? Who cares? Like I told you, whether you’re guilty or innocent doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is whether Linda convinced the jury you did it, and I assure you, she did that.”

“Still.” Noah had heard Thomas’s lecture before. “Thomas, on a firing squad, they always put blanks in one of the guns. And you know the reason? So that everybody on the firing squad can sleep at night, saying to themselves, ‘There’s a chance I didn’t do it.’”

“So what’s your point?”

“If I plead guilty, Maggie will never be able to sleep again. It will ruin her life. I can’t do it to her.”

“But you’ve got to think of yourself now. She’s not thinking of you. You have to be thinking of you.”

“I couldn’t sleep at night knowing what I’d done to her.”

“They’re going to convict you, man!”

“But at least she can say to herself, somewhere, that I didn’t do it. She’ll never have heard from me that I did it. The same goes for Caleb. I can’t do it to him, either. He already gets bullied.”

“But what if it means you get out sooner? Caleb’s only how old now?”

“What makes you think he’ll want to see me, after I plead guilty to murder?”

“He might not want to see you anyway!” Thomas threw up his heavy arms.

“Pleading guilty ensures it. If I plead guilty, well, I explained it. I just won’t do it.”

“It’s your life.”

“Mine isn’t the only life to consider. I have to think of Maggie and Caleb.”

“You’re being noble.”

“I’m being a husband and a father.”

“Exactly why I’m single.” Thomas snorted. “Noah, you’re going against my express legal advice. What would you think of a patient who did that?”

“You need to come to a place of acceptance,” Noah said, without elaborating.“My patients are eight years old. If a mom or dad didn’t take my advice, I’d figure they’d had their reasons.” Noah encouraged his parents to get second opinions. He understood it, himself. Caleb had been late to babble as a baby and as he reached a year and a half, he’d shown difficulty repeating words like mommy and daddy. Noah had suspected he had childhood apraxia of speech, which was hard to identify in pre-school children. The pediatrician had disagreed, but Noah had been right.

“If this came up on appeal, I’d be considered negligent.”

“You’re not. I’m not appealing anything. Thank you for trying. I appreciate it.”

“Damn, you’re tough!” Thomas folded his arms.

“You need to come to a place of acceptance,” Noah said, without elaborating.

__________________________________

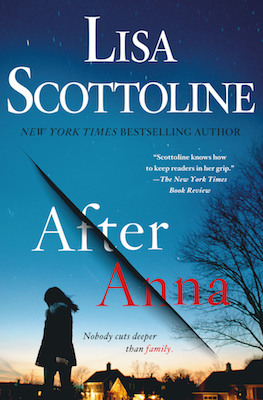

From After Anna. Copyright © 2018 by Lisa Scottoline and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.