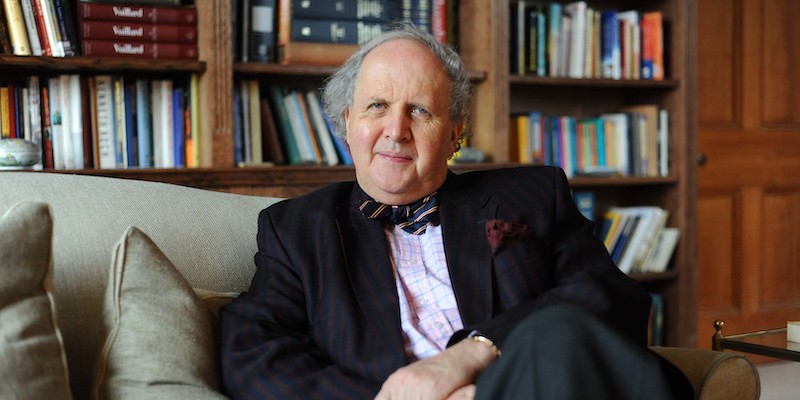

It’s the rare writer whose interior world is so full of story it spills out, on average, into four books a year. From the beloved No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency to the Isabel Dalhousie series, 44 Scotland Street to countless children’s books, Alexander McCall Smith writes with the moral imagination of a keen optimist, someone whose joy comes from exploring the many facets of human goodness. He makes you love his characters—their civility, quirks, and moral core—and brings a soft, welcome humanity to a harsh and distressing time.

In The Department of Sensitive Crimes, the first in McCall Smith’s new series, we meet a Ulf Varg, a Swedish detective who investigates particularly strange crimes in the city of Malmo, whimsical cases (a stabbed kneecap, an imaginary boyfriend gone missing) that come to light not by careful logic, but by the subconscious uncovering of, as his therapist says, “what you think without thinking.” Varg and his deaf, depressive, lip-reading dog Marten are a charming and heartfelt pair.

McCall Smith is perhaps best known for his No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency stories, mysteries I grew up reading; Mma Ramotswe and her milieu—red bush tea, Tlokweng Road Speedy Motors, the bustle of Gaborone—have a special place in my imagination, and beyond the careful observation, gentle suspense, and endearing conflicts, the “traditionally built” detective was a childhood friend. It was a pleasure to catch up with Alexander McCall Smith about his latest foray into Scandinavian crime, his limitless flow of stories, and Freud.

Camille LeBlanc: The Department of Sensitive Crimes is the first novel in a new series about Ulf Varg, a charming Swedish detective in the Sensitive Crimes Department in the city of Malmo. What inspired this new character and setting, and what are some of the challenges of starting a new series?

Alexander McCall Smith: Like so many others, I have enjoyed the many highly entertaining Scanidavian crime novels and television series that have been published and broadcast in recent years. I thought it would be fun to participate—from the outside—in this genre.

You call this novel Scandi-Blanc, “a wholly original genre of fiction marked by unusual cases,” in contrast to Scandi-Noir, the bleak, Nordic-set, morally ambiguous and oft-violent genre of crime fiction. What are you looking to explore by bringing this particular kind of levity to a traditionally dark genre?

There is a point, I think, when the dark and dismal becomes almost a parody of itself—when the bleak aspects of life may be so overstated as to become comic. Some Scandinavian Noir presents such a grim view of humanity that one is tempted to take a pin to it and deflate it.

A quaint comedy punctuates so much of your writing, especially in Sensitive Crimes, which includes investigations about a stabbing in the knee and a missing imaginary friend. Is humor important in your vision of what makes a good mystery?

I think that humour can play a major part in any genre. Crime fiction is traditionally the preserve of the rather hard-bitten investigator and the rather nasty perpetrator. Why not turn the whole thing on its head? All human situations have their humorous potential—even those involving crime. And there have been many other crime novels in which humour plays a part.

Psychological insights and philosophical quandaries are often woven into your fiction, and Sensitive Crimes includes scenes of Varg’s therapy sessions, in which he and Dr. Svensson discuss Kierkegaard, the unconscious, and the differences (or lack thereof) between policemen and analysts. Does philosophy play an important role in everyday life and work, in your experience?

I am interested in philosophy and very much enjoy reading philosophical works. Philosophical issues abound in our day-to-day lives—moral problems of one sort or another confront us everyday. I am also interested in psychology and the exploration of human motives and emotions. I like reading Freudian literature, which is often very colourful and exotic in its particular way.

You’ve written over 100 books: short-story collections, poetry, non-fiction and children’s books—a truly prolific career, and you don’t seem to be slowing down. Do you ever struggle with writer’s block? Where do you look for inspiration?

I count myself very fortunate that I am able to write rather quickly. I find that I do not have to sit down and scratch my head for ideas—they come to me all the time, throughout the day and even at night. My dreams have elaborate narratives and sometimes these are reflected in what I write. So, touch wood, I have yet to suffer from any form of block. My problem is the opposite—I have notebooks full of plots and characters that I fear I shall never have time to use.

As to where I look for inspiration: I find it everywhere—in things that people say; in stories that people tell me; in the news reports I read in the papers; in chance remarks overheard on a train or in an aeroplane; in the way people look; in the way they talk to one another; in poignant sights seen by the side of a road; in all the colour and variety of the world.

Last year marked the 20th anniversary of the first No. 1 Ladies’ Detective Agency books. How has your relationship to that series evolved over so many years with Mma Ramotswe and company?