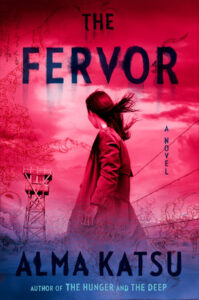

Something happened on my way to writing my next novel, The Fervor (Putnam): it became personal.

The Fervor marks the first time I’ve written a main character with the same ethnicity as mine, Asian American. I had no idea what a different experience this would be.

Like my previous historical horror novels, The Fervor has multiple POV characters. The main character is Meiko Briggs, a Japanese woman who was sent by her family to America to wed a Japanese man in the Seattle area. (In the years before the war, there were 30 Japanese men for every Japanese woman on the west coast and a thriving matchmaking business back in Japan.) Her life is upended when she falls in love and marries that man’s friend, who is white. Then Pearl Harbor happens, the husband (who is a pilot) joins the Army Air Force, and Meiko and her child are sent to the internment camp.

When I started work, I didn’t think it was a big deal. Meiko was just another character and it was my job to slip into her head, as I do with all the POV characters.

Only it wasn’t that simple. The ghosts of my past kept dropping in, insisting on being heard.

My mother was Japanese. She married my father, who was white, when they met after the war. My mom was a product of her time and culture, demure and quiet, but she was also shaped by her experiences after the war. Complete strangers would come up to her in public and say hateful things (much like the anonymous assailants who attack Chinese grandmothers on the streets today). Until she died at 91, she hid in her room every December 7th, Pearl Harbor Day.

It was more than the influence of WWII. Being an Asian woman means navigating stereotypes and others’ assumptions. I had the privilege of writing about this in the foreword of the Stoker Award-winning anthology of science fiction, fantasy, and horror written by Asian women, Black Cranes: Tales of Unquiet Women. There are stereotypes thrust on us, most recognizably the submissive geisha or the dangerous, sexualized dragon lady. There are societal expectations: you’re servile, meek, and accommodating.

When I first wrote Meiko’s chapters, I channeled my mother. Meiko accepted what happened to her, as did the Japanese who went obediently to the prison-camps (even though they had done nothing wrong). However, it didn’t work. She was too passive to make a good leading character. Protagonists must act. They must show growth. They must be changed by their ordeal or quest.

So, instead of having Meiko wait for someone to rescue her, she became the hero of her story. As I wrote Meiko, I was surprised by the amount of anger she felt—well, not entirely surprised, because it was anger I’d felt at various points in my life. You know: being told you should be seen and not heard, and that you should be grateful for what others choose to give you rather than what you deserve. It felt good to let it out. It felt right.

I suspect that Meiko’s anger will resonate with a lot of readers because there’s a lot about The Fervor that feels uncannily current. COVID made us all prisoners in our own homes. New policies came out seemingly every day to control heretofore unregulated aspects of our lives (where we can go, what goes on in our children’s classrooms, what products show up on the grocery store shelves). Normal was turned on its head and refuses to right itself.

Whose secrets are these, anyway?

One of the main challenges is that people close to you will wish you wouldn’t. It doesn’t matter if you’re not telling actual secrets. For some, feelings are not meant to be shared, particularly if they’re not your own. Some members of my family (they’re a private bunch) undoubtedly do not like that I mentioned my mother in the earlier paragraph. Am I allowed to share my mother’s shame and embarrassment? Does it matter that she’s passed?

Tough questions. Perhaps I need to consult the Ethicist in the New York Times. Yet, as a novelist, I feel that it’s my job to use my experiences to make art that helps others understand and navigate the world—which includes their feelings. Some may read The Fervor to understand what it’s like to be female and Asian. Some may gain an empathy for those who were imprisoned in the camps. I like to think that The Fervor may help other Asian women understand that their anger at the way they’ve been treated by the world is not only understandable, but justified.

What is fiction but the marriage of truth and imagination?

When I agreed to write on this topic for CrimeReads, I researched what other writers have had to say on the subject. The results were simultaneously too much and too little. Too much because for many writers, all fiction builds on a foundation in reality, grows from a tiny seed taken from the life they know. At the same time, too little has been written, possibly because the inclusion of the personal in their fiction is a source of anxiety. We fret over whether readers will mistake us for our main character and assume we did (or wished we’d done) the terrible things that our characters are guilty of.

It’s worse when your story overlaps with that of your family. Even if you’re not explicitly writing about them, they will assume that you are. For instance, The Fervor is partially set in Minidoka, one of the internment camps. My husband’s family—parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins—was interned at Topaz. It would be natural for them to be concerned that I might’ve drawn on the experiences they shared with me, but of course I didn’t.

For one thing, the stories from my in-laws and other sources didn’t fit the specific scenes necessary for the book. Novelist Lee Matalone described this in a January 2020 essay she wrote for LitHub, On the Line Between Truth and Fiction When Writing About Your Family. “Being a writer of a certain type of fiction… is about taking reality and making it make sense for the narrative at hand,” she wrote, which just about sums it up. What I got from people who’d been there were descriptions of what the camps were like and how they functioned, how the internees were treated and, most importantly, how they felt about their situation. All those bits get swirled into the background and inform what the characters say and feel.

Many who went through the camps didn’t talk about their experience, not even to the rest of their families. They were embarrassed by what their country had done to them. Some were embarrassed that they didn’t fight back harder (they were told they had to be model citizens to disprove what was being said about them). It’s a very private experience.

At the same time, it continues to be an important civil rights lesson for this country. After 9/11, you may recall, some Americans were calling for the internment of people of Arab descent. This didn’t happen, at least in part, because enough people remembered the lesson of the Japanese internment camps. That for America to do such a thing again would be wrong. Does the need to educate Americans about what happened in the internment camps outweigh an individual’s preference for privacy?

These are the things a writer struggles with.

***