Secrets are fascinating, especially when they simmer in the pages of a file that only the privileged few ever get to see. A confidential file can decide the fates of people or overthrow nations. It can catch a killer or a spy. Government agents have risked all to protect or retrieve these files—especially in fiction. Intelligence services and secret police agencies around the world, especially in authoritarian countries like the USSR and East Germany, made ordinary citizens the subjects of secret files, proof the government was watching them.

My fascination with secret files came early. I was 20 years old, an intern at the State Department in Washington, assigned to the office of [redacted]. My security clearance allowed me access to most of the files. When there was a lull in my official work, my superiors encouraged me to read, to fill myself up on the secret knowledge collected in the cabinets.

The files weren’t just lying around, of course. I had to enter the code to get into the office, and another to unlock the cabinets. Once inside, I roamed through the documents, following the thread of any subject I chose. The creation and uses of the [redacted] weapons system occupied me for weeks. Before we left at the end of the day, all files had to be locked up again. At night, security officers came to make sure we had done it. They would sometimes leave us little signs they were watching us. A card pinned to the wall turned the wrong way, or a cup of pens moved to the wrong place.

The classified file has played a big role in crime and espionage fiction. My favorite stories feature an investigator who is comfortable submerged in the details a secret file can offer. Characters like George Smiley from Le Carré’s Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, who used files to hunt for a Soviet mole in British Intelligence.

But what exactly is it that gives the confidential file its lustre? Is it just the promise of forbidden knowledge?

That’s a big part of it. But I believe there’s more hidden between the fussy covers of a file folder. After all, a good deal of the information in a confidential file isn’t necessarily secret or forbidden in and of itself. It is data, the accumulation of small facts that can be put together like a puzzle. In countries where intelligence agencies and the police overlapped—where even a petty theft could be considered a crime against the State—the collage of information in a secret file could have dire consequences.

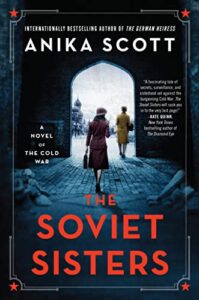

In my new novel, The Soviet Sisters, the files of the KGB and the Soviet secret archives play a central role in Vera Koshkina’s quest to uncover the truth about her sister’s past. In my research, I dug up translations from secret police files from the 1920s until deep into the Cold War. Soviet investigators often recorded the tiniest details about the suspects they were watching. There could be photos, newspaper clippings, undelivered letters, wisps of overheard conversations. As researcher Cristina Vatulescu writes, “The suspicious gaze of the secret police turns everything into incriminating evidence.”

In police states like the USSR, investigating a crime was less important than discovering who the suspect truly was, and how they had become a criminal. The investigator was out to redefine the very identity of the suspect. Using the tiny facts that landed in his file, the investigator reduced his suspect to a label: spy, collaborator, saboteur, counter-revolutionary. Some files went into surprising depth about a person’s life and history. The secret file became a piece of biography, a psychological portrait and tool, not just a collection of facts. No secret file could paint a complete portrait of a person, but all those tiny facts, and what they might mean, are still tantalizing.

If a confidential file isn’t concealing personal secrets, it may be hiding big ones—state secrets. The archives of the Soviet Union are still some of the most guarded in the world. They were open for only a short time in the 1990s after the fall of the USSR. Soviet archivists were known to have power: they were often the last people authorized to read a secret file, and if they found some interesting new angle to pursue, could call for the opening of new files and new investigations. The preservation of this knowledge—the keeping of state secrets—is serious business. We can learn a lot about a country by finding out what it doesn’t want the world, or its own people, to know.

In the short time researchers had access to the Soviet archives, they found fascinating and puzzling state secrets. We now know how Stalin tried to obscure the facts around the death of Hitler. The Red Army found Hitler’s remains in the last days of the war, and his dental assistant identified him via dental records. But Stalin was crazy about secrets, the power of holding back information. He ordered the dental assistant deported to Siberia because the circumstances of Hitler’s death had become a military secret. The truth was buried in classified files in Moscow.

Painful secrets can come to light when confidential files are finally opened to the public. The files of the Stasi became available after the fall of communist East Germany. Citizens could apply to read their own files, to find out what information the Stasi had collected about them. As a whole, the files exposed the true extent of East Germany’s system of informants. Neighbors and coworkers had denounced each other to the secret police, sometimes for petty reasons—a personal slight, or to get access to an apartment. Citizens that had been persecuted under the regime could finally see who had betrayed them. The files named the East Germans who had been informants themselves, a secret they had hoped would never come out.

A file stamped confidential will always be a temptation, an invitation to peek into lives and stories we’re not supposed to see. Once we gain hidden knowledge, the secret is passed onto us, and we have to decide what to do with it. As much as I’d love to talk about [redacted] or even [redacted] that I learned in the confidential files at the State Department, my lips are sealed.

Further reading: Police Aesthetics: Literature, Film and The Secret Police (Stanford UP, 2010) by Cristina Vatulescu.

***