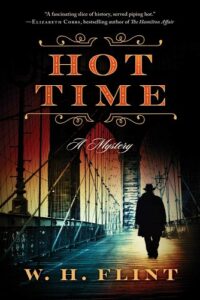

When I decided to set my Gilded Age novel Hot Time during the real-life heat wave that ravaged New York City during August 1896, I imagined that the hellish weather would intensify the drama. But as the book took shape, I found the oppressive heat elbowing its way to center stage alongside the other principal characters—even such imposing figures as Theodore Roosevelt and J.P. Morgan–until the weather permeated every page, amplifying the characters’ misery and even helping to drive the plot.

Hot Time unfolds in a roiling city where luxurious wealth exists side by side with abject poverty. The story centers on the (fictional) murder of the real-life publisher William d’Alton Mann, who made a fortune blackmailing the crème of New York society over their romantic and financial peccadillos. After Mann’s murder is ruled a simple robbery-homicide, the case comes to the attention of Otto “Rafe” Raphael, Commissioner Roosevelt’s assistant and one of the first Jewish officers on the N.Y.P.D. At the risk of his own career, Rafe launches a rogue investigation, which in the midst of an overheated presidential campaign, leads toward ever-higher echelons of William McKinley’s Republican Party. After a homeless newsboy, Dutch Maier, becomes an inadvertent witness, he turns to Rafe for help.

To Dutch and Rafe and all the characters, the heat is inescapable. For ten brutal days that August, New York (like much of the East Coast and Midwest) sweltered through temperatures in the 90s, with humidity close to 100 percent. The suffering was terrible, especially in the packed, unventilated tenements on the Lower East Side, where indoor temperatures could reach 120 degrees. Throughout the city, laborers collapsed on the street; skinny-dippers drowned in the East River; sleepers who had climbed onto rooftops and fire escapes hoping for a cool breeze rolled to their deaths. By the time the heat wave broke, an estimated 1,300 people had died in Manhattan and Brooklyn alone.

“For now, these hot days, is the mad blood stirring,” Shakespeare wrote in Romeo and Juliet, and the observation was just as apt three centuries later. During the heat wave, or “hot wave,” as it was called in 1896, the New York papers published dozens of stories of people literally driven mad by the weather. Suicides spiked, including a 15-year-old baker’s assistant, a new immigrant from Poland, who hanged himself at work rather than face another day tending the ovens. In Jersey City, one desperate man ran from his apartment at 3:30 in the morning, screaming, “Murder! Police!” Three men in straw hats, accompanied by three dogs, had broken into his house, he told the responding officer, but the patrolman found neither man nor beast. The victim was taken to a hospital, where he died three hours later of heatstroke.

As every cop knows, and as a century’s worth of research confirms, violent crimes such as murder and assaults spike in hot weather, and the hotter the weather the worse the crime. During the 1896 heat wave, newspapers also carried stories of unprovoked attacks. One man refused to go to work, then tried to shoot his wife and child before lying down on his bed and turning the pistol on himself. Another victim asked his friend and fellow railroad worker, “How do you like the heat?” In answer, the friend pulled a pistol from his pocket, wounded him, then shot himself in the head.

As to the cause of the seasonal uptick in violence, some experts suggest that high temperatures increase irritability and aggression, while others point to the fact that people may spend more time outdoors in search of cooler air, which brings them into closer contact and increases the opportunity for conflict. Generally the temperature-crime link appears strongest in crowded areas whose denizens are young and poor—which certainly describes the Lower East Side of Hot Time.

In 1896, cops on the beat suffered especially. Whereas other New Yorkers were free to don as little clothing as propriety allowed, the police were still required to wear their helmets and their wool, navy-blue tunics. And not only were patrolmen forced to handle surging crime and mental health crises, they were also called upon to convey tens of thousands of heat-stricken residents to hospitals, after police wagons were pressed into service as makeshift ambulances. They even had to field complaints about mad dogs and the thousands of decomposing horse carcasses piling up on city roadways.

The city government was slow to react to the crisis, for instance refusing to allow sleeping in public parks, which could have saved many lives. But eventually the administration did take steps to alleviate the suffering, such as hosing down the streets and ordering the floating public bath houses in the East and Hudson rivers to remain open around the clock. As president of the board of police commissioners and a member of the board of health, Theodore Roosevelt proposed that the city dispense free ice. Even before the heat wave, the commodity had been an unaffordable luxury for the poor, but now the need was crucial, not only for preserving milk and other foods but for treating heatstroke. When the city appropriated $5,000 for the plan, the N.Y.P.D. took charge of distribution.

As tens of thousands of the poor lined up to receive hundreds of tons of ice over the next few days, Commissioner Roosevelt traveled from precinct to precinct and ventured into the tenements of the Lower East Side. The scenes there were “strange and pathetic,” he wrote his sister. In fact, in his excellent history of the heat wave, Hot Time in the Old Town, Edward P. Kohn suggests that Roosevelt’s experiences during those ten days in August helped to shape the progressive philosophy that would guide his policies as New York governor and later as president.

In my novel Hot Time, the heat and the plot both reach a fiery climax on a sweltering evening in Madison Square Garden. As though the temperature, crime, and mortality weren’t enough for the police and other New Yorkers to bear, the real-life heat wave struck during the largest public gathering of the year—the campaign rally of Democratic presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan. Fresh from his galvanizing “Cross of Gold” speech in Chicago, Bryan had dared to venture into McKinley territory, hoping to summon rhetorical lightning once again. On the night of August 12, he drew more than 10,000 supporters to pack the Garden, where the temperature reached over 100 degrees and men wielding palmetto fans shed their suitcoats and transformed the arena into a sea of white shirtsleeves. Commissioner Roosevelt, responsible for security at the event, ordered ambulances to stand by and set up an emergency clinic to treat the inevitable cases of prostration. Meanwhile, at least in the novel, as the crowd sweats through Bryan’s populist message, they have no idea that a murderer is skulking among them, pursuing his next victim. And so, in fiction, as in life, the heat wave begets a crime wave.

***