Of course the Germans have a wonderful word for ‘Gothic novel’. Schauerroman. Literally: “shudder-novel”. A story that makes you shiver with fear. Because Gothic is the literature of the menacing and the macabre.

It’s the stuff of nightmares.

But how does such a dark art translate in sunny Australia? How do you cause your readers to shiver when the temperature sits stubbornly above 80 degrees?

Gothic influence has been loitering creepily in Australian literature ever since European settlement. In 1788, when the British began shipping their convicts to Australia, Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Ontranto had recently been published in England and so the British transported the Gothic mode along with their very worst criminals.

On arrival, however, they found a landscape that was at once familiar and unnervingly strange. A place where swans were black instead of white. Where trees refused to shed their leaves. Where the seasons were perversely reversed.

In response, many Australian Gothic writers turned inwards, creating psychological thrillers that owe more to the American Gothic tradition, and to writers like Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne who were busy using psyche as setting.

Others developed an antipodean take on Gothic, choosing to work with the landscape they had. For these writers, it didn’t matter that Gothic is all about disintegration (moral and literal), and that Australia has no crumbling castles within cooee. The vast, alien Australian landscape—with a desert centre more than twice the size of Texas—offered a suitably ominous setting for whatever Gothic story local writers could dream up.

Moreover, novels such as Kate Grenville’s The Secret River recognize that Australia has been a haunted landscape ever since our Indigenous people were dispossessed.

Perhaps because of our colonial past, at the (dark) heart of Australian Gothic fiction is a fascination with the familiar versus the uncanny.

The horrific and the mundane are often placed side by side so that readers view the everyday in a new light. (Far more terrifying, for instance, if the creature beheading your chickens is not some fantastical beast from the woods, but the neighbour you wave to each sunshiny morning.)

Which brings us back to all that sparkling sunshine, those blisteringly blue Australian skies—these only serve to heighten Gothic’s long shadow. After all, isn’t the nightmare more terrifying if it unfolds during broad daylight?

Here are 10 classic Aussie novels to make you shiver despite the sunshine.

And the Ass Saw the Angel, Nick Cave

Aussie musician Nick Cave has long been considered the Gothic god of rock. So it’s no surprise that his love for Southern American Gothic literature looms large in his fiction, too. Cave’s first novel And the Ass Saw the Angel features outcast Euchrid Eucrow, from the (fictional) fundamentalist town of Ukulore, in the Deep South. It has Faulkner’s fingerprints all over it.

The Dressmaker, Rosalie Ham

The outback’s not often synonymous with Gothic. Nor is it known for haute couture. Rosalie Ham combines desert, dresses and a healthy dash of darkness in her savage story about a small town with a suspiciously high body count. Now a feature film starring Kate Winslet.

The Secret River, Kate Grenville

Kate Grenville’s tale of first encounters is inspired by the author’s own family history. Shocking and tragic, The Secret River chronicles the life of Will Thornhill, a convict from the London slums who evades execution only to be deported to Australia—“a place, like death, from which men did not return”.

Picnic at Hanging Rock, Joan Lindsay

Valentine’s Day, 1900. A clutch of corset-clad schoolgirls picnic at Hanging Rock and, when four girls disappear, two are never seen again. The unsolved mystery of Hanging Rock—and the trope of the lost child in the bush—speaks deep to the Australian psyche. So much so that many readers (mistakenly) believe the story to be true.

The Dry, Jane Harper

Don’t let its detective fiction façade fool you; The Dry is as much a Gothic novel as it is straight-up crime. From the dry crackle of the undergrowth, to the heat haze on the horizon, Harper’s landscape might be vast but the mood is mercilessly claustrophobic. Film rights have been optioned by Reese Witherspoon.

My Life as a Fake, Peter Carey

Peter Carey’s My Life as a Fake is part true story, part reimagining of that Gothic classic: Frankenstein. Based on the most infamous literary hoax in Australian history (the Ern Malley Affair) Carey creates a seven-foot giant called Bob McCorkle who rises from his creator’s imagination to rival Mary Shelley’s infamous monster.

Past the Shallows, Favel Parrett

If, as academic Gerry Turcotte says, Australia is: “… Gothic par excellence, the dungeon of the world” then Tasmania is the trapdoor in the floor. Moody, at times treacherous, our southern-most island is the setting for its very own brand of Gothic fiction. Tasmania has inspired many Australian stories, and Favel Parrett’s devastating debut about three brothers growing up on the remote south coast of Tasmania is as good as any of them.

Black Juice, Margo Lanagan

Margo Lanagan’s Black Juice features ten weird and wonderful short stories, including “Singing My Sister Down”, which won the World Best Fantasy Award for Best Short Story. Lanagan has since published Tender Morsels—a black retelling of Grimm’s (already very dark), “Snow White and Red Rose.”

See What I Have Done, Sarah Schmidt

While set in the USA, See What I Have Done is the debut novel from Aussie author Sarah Schmidt. Based on the infamous Borden murders that took place in Massachusetts in 1892 (“Lizzie Borden took an axe and gave her mother forty whacks, When she saw what she had done, she gave her father forty-one.”); Schmidt’s story is a feverish read.

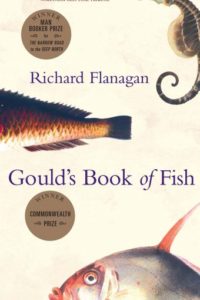

Gould’s Book of Fish, Richard Flanagan

Again set in Tasmania—this time in a penal colony, only a short walk north of hell—Gould’s Book of Fish follows the eponymous Gould, convicted forger and painter of fish. This is a story where magical realism meets barbarism. Equal parts fantastical and grotesque.

Featured Image: Russell Drysdale, Evening.