Some people are great at movie trivia. Some know all the U.S. state capitals. Me? I’m a walking encyclopedia of famous authors who have committed crimes. (Yes, I’m as much fun at parties as I sound. Invite me, post-COVID.)

This niche interest started when I began reading about the sixteenth-century English poet Christopher “Kit” Marlowe for a college literature class. Usually, the bios of classic British authors are pretty easy to skim: went to Oxford and/or Cambridge, moved to London, published some writing, racked up debts, died eventually. Now, to be fair, all of these facts are also true for Marlowe. But that’s leaving out the good parts.

There’s the 1589 arrest for murder. The dramatic seven-year career in international espionage. The 1592 arrest for counterfeiting money. The other 1592 arrest, that one for brawling. The 1593 arrest for atheism. The threatened 1593 arrest for sedition, which only didn’t happen because Marlowe was stabbed first.

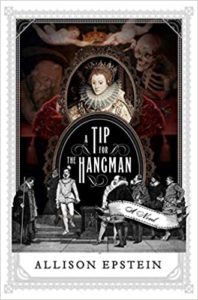

As a longtime fan of crime fiction and historical crime fiction in particular, Kit’s biography was like catnip for me. I went deep down the research rabbit hole and never looked back. One result of this research is my first novel, A Tip for the Hangman. The book takes the covert and criminal activities in Marlowe’s life and reshapes them as a spy thriller, complete with secret codes and international missions. I hope it’s as much fun for others to read as it was for me to write, because I had a blast.

The other result? Tell me that a canonized author committed a weird crime, and you have my complete and undivided attention.

More literary icons have been criminals than your high school English teacher might have led you to believe. Take Marlowe’s contemporary, Ben Jonson, who stabbed an actor in a street brawl. That’s right: Jonson, England’s first poet laureate, got his start by murdering a man in a swordfight. He barely escaped death by hanging for the crime, calling on an obscure legal precedent that said the executioner couldn’t hang a man who could speak Latin.

Then there’s Samuel Pepys, whose extraordinarily detailed seventeenth-century diaries are one of the most-often-cited primary sources of the English Restoration. More interesting—to me—is the fact that Pepys was arrested for high treason not once, not twice, but three separate times. And while none of these charges stuck, he did spend time under lock and key in the Tower of London for a different, equally splashy crime: piracy.

(Where is my ten-part miniseries about Pirate Captain Samuel Pepys, Netflix? Must I do everything myself?)

Robert Louis Stevenson, of Treasure Island fame, was arrested twice: once under suspicion of being a German spy, and once for a snowball fight that got out of hand. The French surrealist poet Guillaume Apollinaire was briefly—though wrongly—arrested for stealing the Mona Lisa. Thomas Malory, author of Le Mort d’Arthur, was most likely a notorious outlaw convicted of robbery, cattle theft, extortion, attempted murder, and church robbery.

There’s something about this list of canonized secret criminals that delights me to my core. We’re all used to the archetype of the stay-at-home author who sits by the fire with a cup of tea and composes grisly murder mysteries. I’m a broadly law-abiding writer myself, with little but a handful of parking tickets to my name. I have no desire to turn to murder, art theft, or piracy in my spare time—but these men did, and I find myself yearning to figure out why.

I also love the sheer rebellious pleasure of putting the fun back in classic lit. Every one of us could tell the story of a “great” book we hated entirely because we were forced to write a timed essay on it in English class. Knowing the salacious backstories of the men behind the canon re-genres those books, in a way. It feels like taking the dusty classics off the shelf and slapping a new, more colorful jacket on them—one that’s just as much mystery, thriller, or true crime as it is literary fiction.

As an author of historical fiction, criminal authors have one more powerful draw: we have access to their writings, and all the psychological insight that can yield. Sorry, Roland Barthes: when I’m writing biographical historical fiction about writers, “death of the author” is off the table. To write A Tip for the Hangman, I dove into Marlowe’s work and let my interpretive brain run wild. How much of the notoriously bloody Tamburlaine the Great reflected Marlowe’s own thoughts on revenge and justice? What can we learn about his espionage tactics from The Massacre at Paris? There’s no way to know for sure, but from a crime writer’s point of view, it’s too much fun not to speculate.

There’s a narrow line to walk here, of course. Some authors have committed crimes that seem endearing with a few centuries of distance: piracy, treason, espionage, getting entangled in a counterfeiting operation in the Netherlands. Other crimes are of a different stripe entirely: the kind that makes it difficult or distasteful to engage with the author at all. Take William S. Burroughs, for instance, who murdered his second wife and barely served time for it. Or Ezra Pound, modernist poet and notorious fascist collaborator during World War II. Or any number of writers through the ages who use the authority of their position to sexually harass or assault those with less power.

Beyond that, the phenomenon of the criminal author is almost entirely a function of white male privilege. The canon has only opened to women and people of color in the last century, if not the last few decades, so it’s no surprise the writers I’ve mentioned above are all white men. And it’s impossible to imagine a person of color committing any of the crimes I’ve described and escaping as lightly as these men did. Race, gender, nationality, class, religion—all the complicated facets of identity are deeply at play here, and it’s naïve and dangerous to pretend they’re not.

Just like any time the “bad boy” trope rears its head, it’s worthwhile to think about what behaviors it’s tacitly condoning, and at what point it starts to become a problem. Everyone will need to locate and draw their own line in the sand. For me, it’s a question of feel: as a woman of Jewish heritage, the anti-Semitism in Marlowe’s play The Jew of Malta is something I can look beyond for a good story; Pound’s chummy relationship with Mussolini is not.

Still, these caveats won’t dissuade me from luxuriating in the study of classic literature’s strangest criminals. The grist it provides for the fiction mill is unparalleled. It’s one of the best ways I’ve ever found to turn the marble busts of Literature’s Great Writers back into real people: human beings who made terrible choices, took risks that didn’t pan out, and maybe dabbled in piracy of a weekend.

And let me tell you, knowing all this would definitely have made tenth-grade English more fun.

*