With the success of our first Thorn operation, we did another operation but in reverse. Using a credit card, which we’d later trace to Backpage’s bank account, we posted a picture of an undercover law enforcement agent, included her phone number, and put the ad on Backpage.

It was quite an ordeal to get a picture to use. We couldn’t use a picture from the internet, because we would be contributing to that person’s exploitation or possibly violating copyright law. We also needed something that looked realistic, young, and sexy enough that people would call. No one wanted to volunteer to put their picture up, myself included! But eventually, an undercover officer from another department gave us her picture to use, and we paired it with an undercover cell phone.

The phone began ringing almost instantly and continued to ring for 806 slimy calls and texts within its first two days. At the same time, we advertised a couch for sale on Backpage.

The communications from the men who saw the escort ad confirmed without a doubt that they expected to have all of their sexual desires fulfilled by our undercover officer. Texts, voicemails, and conversations included negotiating “bareback” (without a condom) rates, insistence that oral and anal sex be included, demands for nude photographs and porn clips, and questions about “doubles.” I shuddered, knowing that many of the victims I knew through Backpage were being forced to advertise and were in fact children.

In addition to determining the demand for commercial sex services on Backpage, we also wanted to see whether the other parts of the site were being utilized. Were people actually buying furniture on Backpage as they did on Craigslist? Or was the entire site about commercial sex, and the other pages were merely a cover? The couch post answered that question, by receiving no response. It was a nice, well-priced couch that no one on Backpage was looking for.

By this point, Special Agent Brian Fichtner had been assigned to the case. Reye was busy with everything else and agreed to help out occasionally, but I could not get him assigned full-time. It landed in Brian’s lap in a typical, shit-rolls-downhill-at-DOJ kind of way. He had just been assigned to the newly formed eCrime Unit, but his background was as a narcotics officer. He had never wanted to investigate “computer crimes” in the same way I did not want to take on mortgage fraud. Still, he had started his career as a juvenile probation officer and had the right demeanor for the case. He knew how to talk to teenagers. He was patient, unassuming, and kind. He was smarter than he let on and was a hard worker. I felt like if I could get him really hooked on the case, he was the right person for the job, even though I was sure that at first he wanted nothing to do with it. Early on during the investigation, he went out on medical leave for surgery on a torn bicep muscle, an injury he received teaching a tactical training course to other law enforcement officers at the academy. I was certain that his arm was fine and that he was just trying to get out of the case, hoping that while he was out on leave, some other poor mope would get assigned and then become so immersed in the case that there would be no role for Brian when he got back. But to my delight, Brian got bored during his four-month stint on the couch nursing his bicep injury and began digging into Backpage. He started texting me ideas for the investigation and contact information for some of the victims we had been trying to locate. When he finally came back to the office, he was all in.

With Brian’s help, we continued investigating Backpage’s business structure. Who were the company officers? Where did they live? Where were the offices? Who worked for them, and what did they do? Could we convince former employees to cooperate without alerting Backpage that an investigation was under way?

We knew that the company had been founded by James Larkin and Michael Lacey, the men who initially met with NCMEC back in 2011. Lacey was born in New York, went to Catholic school in Newark, New Jersey, and then attended college at Arizona State University. He protested Vietnam, vocally criticized his school administration, and generally clashed with authority. He ended up dropping out of college and started an alternative weekly newspaper, the Phoenix New Times, for the “sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll generation.” He was never one to back down from a fight and had the words “hold fast” tattooed across his knuckles. Larkin was an Arizona native with a kindred rebel spirit. The two immediately clicked, Larkin becoming the publisher and Lacey the chief editor of New Times as they began building a lucrative media empire. They used their newspaper to criticize politicians and continued to clash with authority, while reaching a broader and more expansive audience. In 2007, to make a point about their First Amendment rights, they published a grand jury subpoena that had been issued to their company, New Times Media. The sheriff then arrested them on flimsy charges. They were in custody for less than a day. And as soon as the charges against them were dropped, they were already filing a blistering lawsuit against the sheriff, which resulted in the county having to pay them nearly $4 million.

We knew if we arrested them, we’d be in for a fight. In fact, we assumed that if they learned that we were investigating them, they would sue us and attempt to get an injunction stopping the investigation before it ever got off the ground. We had heard a rumor that this had happened to another law enforcement agency that had unsuccessfully attempted to investigate them. Even though I knew that it was a righteous case and that a lawsuit against us for pursuing it should fail, the distraction of the state having to defend itself while also trying to build a case could be crippling. If we filed charges while being sued, it could also look retaliatory. It was the kind of situation that could cause a pragmatic and politically savvy attorney general to drop the case and move on rather than to continue to dump resources into what could come off as a controversial First Amendment battle. But I never thought of it as a First Amendment battle. It was a sex-trafficking case.

As the paper business started drying up and online advertising became the future, Larkin and Lacey were in search of a more lucrative business plan. Carl Ferrer was a younger, techy guy from Texas with a background in internet sales. Larkin and Lacey enlisted his help to build Backpage and make them a lot of money. The news part of their business quickly went out the window, and they sold their news company shares to focus solely on expanding (and defending) Backpage.

It turned out that Backpage’s most lucrative product was teenagers. Rich, greedy, and no longer in the business of news, with Ferrer’s help, Larkin and Lacey committed to cornering the sex-trafficking market, no matter how many lives were ruined along the way. On the outside, they looked like successful businessmen. They drove fancy cars, owned multiple homes, and traveled the world for meetings. Even as the news stories about sex trafficking on the site piled up, the business continued to expand.

A few days after our undercover law enforcement agent put up her ad for commercial sex, we wanted to test how quickly Backpage would take it down, if prompted by a law enforcement request. We also wanted to determine what role, if any, Carl Ferrer had in daily operations. We knew that Larkin and Lacey were the majority owners. We knew that Ferrer was the CEO, at least on paper. We didn’t know whether any of them were physically in the office or how involved they were in running the site. We needed to show they had knowledge of what was taking place on their website on a daily basis. Later we would need to prove that they helped develop that content and purposely designed Backpage to function as a brothel. If we arrested them without establishing that knowledge, they could say, “We set this up as an advertising website, and we hired people who look at the advertising. If people are selling other people for sex on there, we had no idea and no involvement.” Or relying on the CDA, they would claim that they were just a platform—a blank page where users could write and post what they wanted—and under the CDA’s immunity provision, we could not prosecute them, as a mere platform for information from others.

That was exactly what we couldn’t afford to let happen—we needed to build a case that would not only prove our charges but also deflate their defenses.

Normally, a law enforcement agent would send an email to a generic Backpage email address to get a sex ad taken down or request additional information about the poster. But Brian called Ferrer directly on his cell phone to see what would happen. Ferrer picked up. Referring to the ad number of the undercover officer, Brian explained that he was investigating a sex-trafficking case. “I suspect this is an ad for commercial sex,” Brian stammered, still a little taken aback that Ferrer had picked up his phone. Ferrer asked what agency Brian was with, Brian told him the California Department of Justice, and Ferrer agreed to take the ad down and send Brian back-end information about the posting.

It was pretty simple, but it showed us that Ferrer was hands-on with the website and was accustomed to receiving calls from law enforcement agencies telling him that there were sex-trafficking ads on his website. He also sent an email to Brian to confirm that he had removed the ad. We now had Ferrer’s email address, which was exactly what we needed to substantiate a specific location for the search warrant.

Our biggest break was learning that Google held Backpage’s email servers. Ferrer’s email address was managed by a Google business platform. Google is incorporated in California, so we had the advantage of being able to serve a search warrant without involving another state.

By this time, we had a lot of evidence. We had the unequivocal purpose of Backpage as a commercial sex hub, from the perspective both of girls sold and of all the buyers who called our officer. We had the communications with NCMEC. We had Brian’s call and email with Ferrer himself. We had the NCMEC victims. And we had many, many reports from other law enforcement agencies and our own detailing ways in which victims were bought and sold using Backpage. We also collected all of the subpoenas from other law enforcement agencies to Backpage in sex-trafficking cases, which showed that Carl Ferrer was inundated, on a daily basis, with law enforcement requests for records related to sex-trafficking cases. If Ferrer printed out every advertisement selling a child for sex, he would have buried himself in paper. We finally had enough to show probable cause that a felony was being committed by Ferrer and that evidence of it would be in emails located at Google.

A Placer County judge signed off on the very first search warrant for Ferrer’s emails.

Google was uncomfortable with our warrant, saying it was a huge swath of information to deliver. At that time, the warrant was sealed, and we were not required to provide notice to Ferrer that we were executing a warrant for his email. Google was obligated both to keep the warrant confidential and to turn over what it had despite its reservations.

Later, a California statute known as the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act (CalECPA) passed, requiring law enforcement to notify suspects when serving warrants to third parties, giving suspects an advantage, especially in white-collar investigations. But an officer could include a sworn statement laying out a justification for delayed notification and attempt to buy extra time. Even if a judge granted delayed notification, the delay would need to be renewed and would eventually expire.

The new law hindered investigations. Once suspects know they are being investigated, it is harder to obtain evidence, identify victim assets in fraud cases, and stay ahead of fleeing suspects. It made longer, more complex investigations especially difficult. But it was a new California law that passed during the course of our investigation, and we had to learn to comply with it.

We were giddy when the package from Google arrived at the Department of Justice. It was just a yellow padded envelope containing a hard drive, but I could hardly wait to see what was inside. Before I or anyone from my team could delve in, the hard drive needed to be properly stored in evidence. The emails were downloaded into a searchable database and then searched for any emails that could involve the attorney-client privilege. The attorney-client privilege generally protects information from disclosure when it is between a person and his or her lawyer and relates to legal advice or future litigation. We were aware of an in-house attorney at Backpage, Liz McDougall, as well as several outside counsel that Backpage executives regularly consulted with. A separate “taint team” segregated any attorney emails into a separate locked file that no one investigating or prosecuting the case could look at. The role of a “taint team” is to ensure that the investigation is not tainted by any breech of attorney-client privilege. Some of the segregated emails would not necessarily be privileged—just because an email is to or from a lawyer does not render it privileged. But to be safe, we would segregate them all. This of course took weeks instead of days, as I impatiently and constantly checked in to see when we might be able to review the evidence.

After the emails were scrubbed for anything that could be attorney-client privilege, we finally got to review them. They showed who Ferrer was communicating with internally to run the operation as well as whom he was reporting to. It was clear that James Larkin and Mike Lacey, longtime founding owners, were still calling the shots.

Some of the emails included spreadsheet attachments. Once downloaded, they showed how much money Backpage was making. It was more than any of us had imagined: millions of dollars each month, just on sex ads in the female-escort section. We were only focused on California, as we only had jurisdiction over California transactions, and were trying to figure out what money came from where. We learned that the defendants operated mainly out of a headquarters office in Dallas, Texas, with another major office in Arizona. Unless the victim posted an ad in California or we could otherwise connect the defendants and their crimes to California, we would not be able to prove that we had jurisdiction. But we were able to divide the ads by city, choosing the largest California cites to analyze.

We also quickly determined that over 90–100 percent of Backpage’s monthly revenue was from the escort section, not the furniture, car, or other sections. It appeared that Ferrer was emailing back and forth with other advertisers to buy bulk advertisements in order to populate other sections of the site. But unlike the escort section, he was not investing in driving traffic to those areas of the site. They were merely a shell. It also appeared that Ferrer was emailing with Lacey and Larkin to provide regular updates about the company, growth strategy, legal and political concerns, and bottom-line financials. Larkin and Lacey would respond with questions, ideas, sometimes jokes.

Larkin, Lacey, and Ferrer were all well aware of Backpage’s role in sex trafficking. Using the search terms “sex trafficking” and “human trafficking” and “child sex” resulted in thousands of emails in which they discussed how to respond to criticism about their role in child sex trafficking, how to work with other major corporations that were wary of them because of their role in sex trafficking, and whether and when to prevent certain pictures from being allowed on their site.

With that evidence, we drafted a new search warrant with a more extensive list of email accounts in a longer date range. We now needed the email accounts of Larkin and Lacey and others whom Ferrer was regularly corresponding with to run what was more clearly looking like a criminal enterprise. The Placer County judge signed off, and we went back to Google with the more extensive warrant. Google lawyers raised their eyebrows at us, but after some wrangling, they ended up giving us the evidence we were entitled to. This took months, and more months, to scrub for attorney-client privilege and download into our searchable database.

From the new accounts, we extracted even more evidence, including more details about the financial workings of the company. We now had a database with millions of emails, and it was overwhelming. I was the only lawyer, and Brian was the only dedicated agent. We were drowning in evidence.

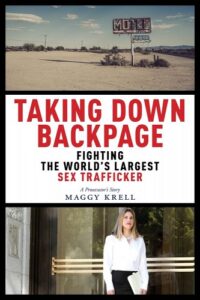

Excerpt from Taking Down Backpage: Fighting the World’s Largest Sex Trafficker by Maggy Krell printed with permission from NYU Press.