Long before #BlackGirlMagic became a thing, a black mystery writer named Barbara Neely was showing the crime fiction community how it’s done.

As many writers will tell you—even if takes them awhile to admit it—you can in fact judge a book by its cover. And the original cover for Neely’s groundbreaking debut, Blanche on the Lam, definitely tells you all you need to know. It features the back of a dark skinned black woman in an orange dress, with her hair up and her hand on her hip. She faces a house, one that would be at home on a Southern plantation. Even though we don’t see her face, we can tell she’s not intimidated. If anything the house—and its occupants—should be worried about her. #BlackGirlMagic indeed.

This was our first introduction Blanche White. Although it wouldn’t be a long relationship—lasting just four books over eight years—it would most definitely be a memorable one, especially for readers and a generation of black mystery writers.

The first in the series, Blanche on the Lam, won the 1992 Agatha Award for Best First Novel, 1993 Anthony Award for Best First Novel and the 1993 Macavity Award for Best First Novel. It would be years before another woman of color won those same awards. (Sujata Massey won the Agatha Award in 1997, Paula L. Woods won the Macavity in 2000 and I won the Anthony in 2018.)

Though she was new to crime fiction, Neely wasn’t some young, naive wunderkind when she published her debut in 1992 with St. Martin’s. She brought a lifetime of experiences and activism to her writing. According to a 2015 Washington Post profile, Neely’s background included a master’s degree in Urban Planning (she also has one in creative writing), work as a journalist and radio talk show host and designing Pennsylvania’s first community-based woman’s correctional facility. She was also a known short story writer, including being published in magazines like Essence.

In fact, the character of Blanche herself was born in a short story. As she told me for a Black Mystery Writer Roundtable I conducted for the Los Angeles Review of Books, “I did not set out to write a mystery. I had a short story published, both a publisher and an agent got in touch with me and asked me if I was working on anything longer. I sent them both the same letter. The letter was about the great African-American novel that I was undoubtedly writing and went on about that for a page or two. And then in the last paragraph I mentioned that I’m writing this other thing with a character named Blanche White blah blah blah and they both wrote me back the same letter saying, “What about that other thing?” So that’s how Blanche got started.”

At the time there were no published full-length mysteries with a black woman as the main character—definitely none written by a black woman herself. As Edgar-winning mystery author Naomi Hirahara noted in a July 2014 blog post for Brash Books—who have reissued all four books in Neely’s series—Blanche White’s arrival on bookshelves also heralded a new voice in crime fiction. Literally. Hirahara noted, “Although author-critic Paula L. Woods refers to Pauline E. Hopkins, who wrote the 1900 locked-room short story, ‘Talma Gordon,’ as the “foremother of African-American mysteries,’ it seems that a black female series sleuth didn’t make it to mainstream U.S. publishing until the creation of Blanche White.”

That would be a ninety-two year gap.

***

It’s important to give context to help understand the sudden interest in publishing a crime novel with the black woman as more than just the sassy black friend. The late 80’s/early 90’s were the beginning of renaissance of sorts in publishing. It was when publishers seemed to realize, “Hey, people will read books with black main characters written by black people.” Houghton Mifflin published Terry McMillan’s debut, Mama, in 1987 and due to her own promotion, the book sold out it’s initial print run. Viking publisher her second book, Disappearing Acts, in 1989. It had a 25,000 copy first printing and was optioned by Tri-star. (She’d later go on to publish Waiting to Exhale in 1994, forever changing publishing.)

At the same time, changes were being felt in the crime fiction world. Gar Anthony Haywood’s Fear of the Dark, which featured a Los Angeles based black private investigator, won St. Martin’s 1988 Best First P.I. Novel Contest. Once published, it went on to be nominated for the 1989 Anthony Award for Best First Novel and won the Shamus Award in the same category. And of course, Walter Mosley introduced us to Easy Rawlins when Devil in a Blue Dress was published in 1990.

In the LARB article, Neely herself credited both McMillan and Mosley for her publishing success: “I really do think I owe more to both Terry McMillan and Walter than I do to the publisher who bought the book. The first Easy Rawlins book had come out, Terry McMillan was selling I believe her first novel out of the back of her car, to the point where she’d convinced the publishing world that indeed there was an audience out there for black books. My suspicion with the first publisher, and I think the suspicion may have been based on some things that were said, was that you know, well, we’ve got Walter Mosley, it’s almost like we’ve got Fred Astaire, let’s see if we can find Ginger Rogers. So I think that their interest in the book was related to the public interest in his book.”

The character was unquestionably a tough guy but not in the traditional sense. First, she was a woman. Second, she wasn’t a professional detective and had no desire to be one.It’s also important to note that with Blanche, Neely went the total opposite direction than all her peers. The character was unquestionably a tough guy but not in the traditional sense. First, she was a woman. Second, she wasn’t a professional detective and had no desire to be one. Blanche is quite content to be a domestic worker. As Neely writes in Blanche on the Lam, “For all the chatelaine fantasies of some of the women for whom she worked, she really was her own boss, and her clients knew it. She ordered her employers’ lives, not the other way around” (page 85 in the Kindle edition).

Even as an amateur detective, she didn’t fit the cozy tropes. There’s no stumbling on dead bodies. The books are very slow-paced and just as much about the everyday minutia of Blanche’s professional and personal lives as they were about investigating a murder. In the first book, no one even dies until about midway through. And although the bodies show up earlier in the other stories, it can still take a lot for Blanche to investigate. But when she does, it’s in a totally unique way you don’t—and can’t—find in your average noir or cozy book.

Blanche uses her societal position as someone often viewed as invisible to her advantage, listening in on private conversations and going through things under the guise of cleaning up after her employers. She also uses her vast network of domestic workers and black folks to learn the secrets that the upper crust white families don’t want anyone to know—and would kill to keep.

The idea of Blanche as invisible is so interesting because she written is someone impossible to miss. From Blanche Among the Talented Tenth:

“She knew she was attractive to the kind of black men whose African memory was strong enough for them to associate a big butt black woman with abundance and a smooth comfortable ride, men who liked women with ate hearty and laughed out loud.”

Yet she’s also often ignored for those exact same reasons.

***

Neely’s background is as an activist—according to Wikipedia, she’s been awarded for that work as well. It’s clear she has something she wants readers to get out of each book besides the satisfaction of knowing who done it. Each novel tackles a different aspect of black American culture—and by extension, American culture in general because it’s the same thing. She goes beyond just racism to tackle color issues, homophobia, political corruption and abuse of women—all things we’re still dealing with two decades later.

The themes aren’t subtle, which is by design. As the Washington Post profile notes, “Neely wanted to concentrate on issues of race, gender and class.” She told the Post, “As an old organizer, you tell people what you want them to know, tell them again, and then tell them you’ve told them.”

A prime example is the name of Blanche White. Someone so dark skinned essentially being named White White was a sore point for Blanche growing up and something she’s still sensitive about as an adult. From Blanche Passes Go:

“Maybe because she so often felt the need to defend her own name, she’d come to believe something could be learned about people from how they said their names—with pride or indifference, as though presenting a gift or calling down a curse.”

There’s also a humor in the books that I’m not sure get enough credit. The Blanche books are as funny as they are blunt. In Blanche on the Lam, she has a brief encounter with an obnoxious, disrespectful white grocery boy that leads her to put a half-serious hex on his private parts. She encounters him eight years later in the final book in the series, Blanche Passes Go. When Blanche recognizes him, it causes her to wonder if her curse indeed worked: “‘Got any kids?’ she asked.”

Needless to say, you wouldn’t find her in The Help. She rings so true because she reminds me of both my grandmothers. (My paternal grandmother was sent “up north” when she was just 9 years old to work in a white woman’s kitchen.) With Blanche, Neely has taken the archetypical Mammy character as a basis and turns it on its do-ragged head. Neely acknowledges this in Blanche on the Lam:

“Blanche was unimpressed by the tears, and Grace’s Mammy-save-me eyes. Mammy-savers regularly peeped out at her from the faces of some white women for whom she worked, and lately in this age of the touchy-feely model of manhood, an occasional white man. It happened when an employer was struck by family disaster or grew too compulsive about owning everything, too overwrought, or downright frightened by who and what they were. She never ceased to be amazed at how many white people longed for Aunt Jemima.”

That wasn’t the only way that Neely made Blanche buck traditions. Blanche is a mother. A best friend. A woman who enjoys having sex. And she’s far from perfect. She’s independent to the point where it interferes in every area of her life. She gets in fights with her best friend because of her stubbornness. She is admittedly ambivalent to her role as mother of her dead sister’s two children. She literally disappeared to California for a year when she first learns she’s become their guardian but by the time Blanche on the Lam opens, even she’s surprised at how much she’s embraced her role as mother. (Those conflicting feelings don’t lessen throughout the series.) In some ways not typical black woman of the 90s. She’s not a Christian. Besides the aforementioned embracing of domestic work, she refuses to wear her hair chemically straightened or hidden under weave.

Blanche is a mother. A best friend. A woman who enjoys having sex. And she’s far from perfect. She’s independent to the point where it interferes in every area of her life.It’s actually amazing how thoroughly modern she feels though even in 2019. The hair. The intense desire to work for herself—even if it’s not a socially acceptable position. The being okay with admitting that she doesn’t want to get married or have children of her own. All things that may have given her a second glance in 1992 yet feel right at home for many black women today. But even as self-assured as she is, she also fully embraces her fears and missteps. When her life is threatened, her reaction is what you might expect. Fear. Those feelings are perhaps best explored in the final book in the series, Blanche Passes Go, where she finally deals with her rape at the hands of a white male employer the eight years prior—a rape that’s only briefly mentioned in previous books.

It makes you wonder what Blanche would be up to today and what her take would be on the Flint Water Crisis, #blacklivesmatter, the scores of black woman finally embracing their natural kinks and curls. Unfortunately, we may never know. There’s a good chance we may never get to read anything new from Neely. It’s not that she isn’t writing (she told us during her roundtable that she was loving writing a series of short stories.) She is. She just doesn’t have any desire to publish them right now.

She didn’t say how long she’s had these feelings, but there’s an almost full circle-ness of her last published novel, Blanche Passes Go, which brings back many of the same characters from her debut. There’s also a final-ness in Blanche herself. You get the feeling that even if she’s not going to be riding off into the sunset but she will indeed be passing go and feeling more than all right about it.

The Essential Barbara Neely

Blanche on the Lam (1992)

Themes: Racism, Invisibility

We meet Blanche White in her hometown of Farleigh, North Carolina as she escapes a courthouse after being sentenced to thirty days in jail for continuing to write bad checks. She hides out working for a rich white family at their vacation home and finds herself breaking one of her own rules by connecting with Mumsfield, a white man with down syndrome set to inherit a vast family fortune. Their connection is based on both being ignored by other members of society. Throughout the book, Blanche is making plans to escape to stay with a family cousin in Boston.

Blanche Among the Talented Tenth (1994)

Theme: Colorism

Two years later, Blanche is in Boston and doing well for herself. So well, in fact, that she is able to spend the summer at Amber Cover, a fancy New England black resort. Unfortunately, a much-hated member ends up electrocuted in her bathtub and Blanche isn’t so sure that it’s an accident.

The Talented Tenth in the title refers to the name made popular by W.E.B. Du Bois to describe the upper-class black people viewed as leaders of their race. So it’s not surprising the story deals with the color issues that black people face within our own culture.

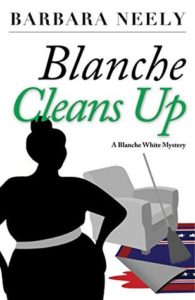

Blanche Cleans Up (1998)

Themes: Homophobia, Environmental Contamination, Political Corruption

In her third book, we get to spend time with Blanche on her own turf—her home in Boston when she takes a job for an extremely conservative Massachusetts gubernatorial candidate with enough secrets for half the population. When Blanche’s family friend who threatened the candidate is killed, she looks into it and of course finds more than she bargained for.

This is my probably favorite of the series, probably because Blanche is so active in her investigation. We also get to spend more time with her two children, Malik and Taifa, even if they’re driving Blanche up the wall with their teenager-ness.

Blanche Passes Go (2000)

Theme: Violence Against Women

In the final book, Blanche is back in Fairleigh and out for revenge against the white man who raped her eight years before. When a white woman turns up beaten and dead, Blanche is convinced her rapist was involved. She just has to prove it. Several beloved characters from the first book make an appearance.