It was time to begin a new book. I had a few ideas. Usually, I begin with a very basic situation and find my way forward from there.

So I wrote a few thousand words about a young woman named Helene who was stuck working at a gas station in a remote and unpopulated corner of Montana. I really liked Helene and her problems, and thought it was a good beginning to a book, but I couldn’t figure out where Peter Ash, the series protagonist, would fit into the story. In fact, I was so unsure that I put it down and started something else.

This time, I began with Peter. I put him in the back of a moving pickup, wrapped in a tarp, his arms and legs tied. He freed his feet and fell from the back of the truck, still stuck in that tarp, then rolled through a cornfield until he came to a stop. The scene was lively enough, with tension and humor, but I still had no clue how Peter had gotten himself in that fix, or what might happen next. It didn’t help me find my way into an actual book.

I tried again. Peter got pulled over by a Nebraska sheriff’s deputy and taken to the sheriff’s office because his license was chronically expired. Some bad people were converging on that town because of a trailer full of money confiscated by the cops, and Peter would, of course, get involved. But the whole thing just felt ridiculous, like a French teenager’s idea of an American thriller, typed directly into a discontinued version of Google Translate.

And all the while, falling asleep at night, I kept thinking about Helene at that gas station in Coldwater, Montana. I liked her. I heard her voice in my head, murmuring softly while I slept. But I didn’t trust her. Really, I didn’t trust myself.

For my first five novels in the series, finding the beginning was something I did instinctively. I had an internal reservoir of stories that appeared almost unbidden. From a random initial idea, the book would take form. It was always the second act, the so-called messy middle, that was challenging. But when writing a series, you eventually have to step outside your instincts and try some new moves. What kinds of stories had I not yet told? What the heck was a “Peter Ash novel” anyway? Those kinds of questions made me second-guess myself into paralysis. It felt like I’d forgotten how to write.

I tried another beginning, then another. Each seemed worse than the last. I was certain the book would never emerge from the fog. In fact, I was probably finished as a writer. I’d have to go back to making my living as a carpenter. But I’m over 50, and my body already aches because of all the years I spent swinging a hammer. Starbucks was probably the only real option for me. I’d read somewhere that they offered health insurance to full-time employees. One flat white with extra whip, coming up.

At times like this, if I am lucky, I remember the opening paragraph from Moby Dick. Whenever Ishmael finds himself “involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses” and feels the urge to step into the street and start “knocking people’s hats off,” he knows it’s “high time to get to sea as soon as I can.”

I don’t own a boat and am not remotely qualified for the Merchant Marine, so I did the next best thing: threw some camping gear into my land yacht and started driving.

I must confess to you here that I do not own any kind of cool car. I used to drive a Toyota pickup I loved dearly, the first vehicle I ever bought new, but she got the cancer real bad and I had to put her down. Because I work at home and Margret actually goes into the office from time to time, she drives the replacement car and I got her old Honda minivan. It’s sea-foam green and sixteen years old, with a hundred and sixty thousand miles on the odometer, which is well into janky but nowhere near classic. There’s a kind of old-car smell that no number of air fresheners can undo. Plus – I know I mentioned this, but it’s worth repeating – it’s a minivan. So, no, not super cool.

But the old girl is paid for, and despite her mechanical quirks, the engine hums right along. She’s built to carry eight, so with just me onboard, she’s got plenty of pep. The driver’s seat is comfortable. The suspension doesn’t mind gravel roads. On rare, unavoidable stretches of the interstate, she’ll go ninety-plus indefinitely and without complaint. (I’ve also found that minivans are somehow invisible to state troopers, who perhaps feel that if Mom and Dad are speeding, they have a damn good reason.)

Now, I have a rule for solo road trips. I’m only allowed to listen to the radio until my local stations fade into static. There’s no way to connect my phone, either by cable or Bluetooth, because back when this car was built, there was no such thing as an iPhone. My phone is turned off, anyway – another rule intended to keep me off email and social media. So once I’m out of FM range, I’m stuck with my own thoughts.

At first, my mind races in the silence. My to-do list, my impatience, my worries and fears and delusions of grandeur. I suffer fits of road rage, the prolonged desire for a double bourbon. Anything to drown out the relentless scurrying of my brain and my self-important despair about this book’s bad beginnings.

But after a few hours, my mind begins to quiet and the ever-changing countryside takes over. The towering clouds, the fields awaiting harvest, the autumn trees clustered on the hilltops and creek bottoms. There is nothing to do but drive and noplace to go but onward. So onward I go, deeper into the landscape. Somehow, I don’t think about the book at all.

That first night, I stop at an almost-empty state park in Iowa. I start a fire in the ring and make a simple supper, then sit and stare at the swirling flames. It’s mid-October and unseasonably cold, near freezing. The wind tears the leaves from the towering oaks, swirls them like snow, piles them into drifts. To stay warm, I build the fire higher. The book is there in the back of my mind now, just barely. I ignore it. The orange coals hiss and pop. My phone remains off. I climb into my bag and fall asleep.

At first light, another fire, a pot of coffee, some bread and cheese and raspberry jam. Then I’m back on the road, headed for Nebraska. By now, I know, somehow, that’s where most of the book will take place, whatever kind of book it will be. It’s getting more insistent now. It likes the look of these flat plains and rolling hills, the contrast of this rich farmland, once the source of American prosperity, now dotted with abandoned farmhouses collapsing on themselves. Single-wide trailers stand alone in patches of dirt with faded blue tarps wrapped over their leaky roofs, rattling in the wind.

By the time I stop for the night along the Missouri River, I know it’s about Helene. I know how she gets from that lonely Montana gas station to a gravel road in Nebraska. I know how she meets Peter, and I know the beginnings of the challenges they will face, apart and together. I don’t know anything else, but I don’t need to. It’s enough. I’m on my way.

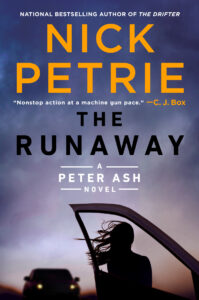

Funny, but writing this now, with The Runaway finished and headed to booksellers, the book feels somehow inevitable. As if I always knew what I was doing. Oddly enough, versions of several false starts found their way into the story. Despite the struggle, nothing is wasted.

This is part of the magic of writing, for me. There is a primitive part of each of us, developed during humanity’s earliest days, when we had nothing but fire to brighten our nights. We sat around the flickering flames and wondered where lightning came from, or why the sun rose and fell in the sky. We told stories to ourselves, and each other, to ease our fears and make sense of the world’s mysteries.

We are all storytellers. Sometimes I forget how far back it goes, this storytelling urge. To remember, all I have to do is turn off my phone, get in the car, and start driving.

___________________________________

The actual quote From Moby Dick, by Herman Melville

“Whenever I find myself growing grim about the mouth; whenever it is a damp, drizzly November in my soul; whenever I find myself involuntarily pausing before coffin warehouses, and bringing up the rear of every funeral I meet; and especially whenever my hypos get such an upper hand of me, that it requires a strong moral principle to prevent me from deliberately stepping into the street, and methodologically knocking people’s hats off – then, I account it high time to get to sea as soon as I can. This is my substitute for pistol and ball… I quietly take to the ship.”