“You talking to me?” excluded, the most iconic lines from Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) are two bits of voiceover narration read from the diary of Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), the disturbed Vietnam vet-turned-insomniac cabbie-turned-would-be political assassin and lethal vigilante-turned-misbegotten public hero.

In the first, Bickle describes the streets of lower Manhattan he traverses nightly as a cesspool of vice and rot, reducing its denizens to “animals” and declaring, “Someday a real rain will come and wash all this scum off the streets.” Later, he turns his jaundiced eye on himself, writing, “Loneliness has followed me my whole life. Everywhere—in bars, in cars, sidewalks, stores. Everywhere. There’s no escape. I’m God’s lonely man.”

Forty-three years later, the quintessence of disenfranchisement captured in Bickle’s lament (based on screenwriter Paul Schrader’s own diary entries during a period of intense personal turmoil) has lost none of its potency or pungency; Taxi Driver’s relevance to our current moment—one beset by mass shootings, the rise of reactionary misogynist and racist political movements, and an upsurge in vigilantism (not to mention a gig economy that has produced millions of new roving hacks)—being all too apparent.

Now, thanks to the highly anticipated/dreaded release of Warner Brother’s Joker, which appears to lift wholesale Taxi Driver’s tone and aesthetic, the archetype of the angry white loner pushed to his breaking point, as previously defined by Bickle, has moved from the fringes of mainstream cinema to the very center of the popular culture.

Such a trajectory is not merely the result of Joker director and co-screenwriter Todd Phillips deciding Taxi Driver would make a good model for his reimagining of the well-worn Batman mythos, as such narratives trace farther back than Scorsese and Schrader’s film. At heart, Taxi Driver is an update of John Ford’s 1956 western epic The Searchers (itself is a revisionist take on the American captive narrative), which similarly centers around a violent and racist outcast taking it upon himself to “liberate” a young white girl from captivity and sexual slavery, but whose true motives are far more disturbing.

Nor was Taxi Driver the first New Hollywood film to use the inherently problematic framework of the captive narrative to tell a brutal story about violent generational and cultural division and provide insight into the psyche of an angry white loner driven to commit an act of mass murder. Six years earlier, there was Joe.

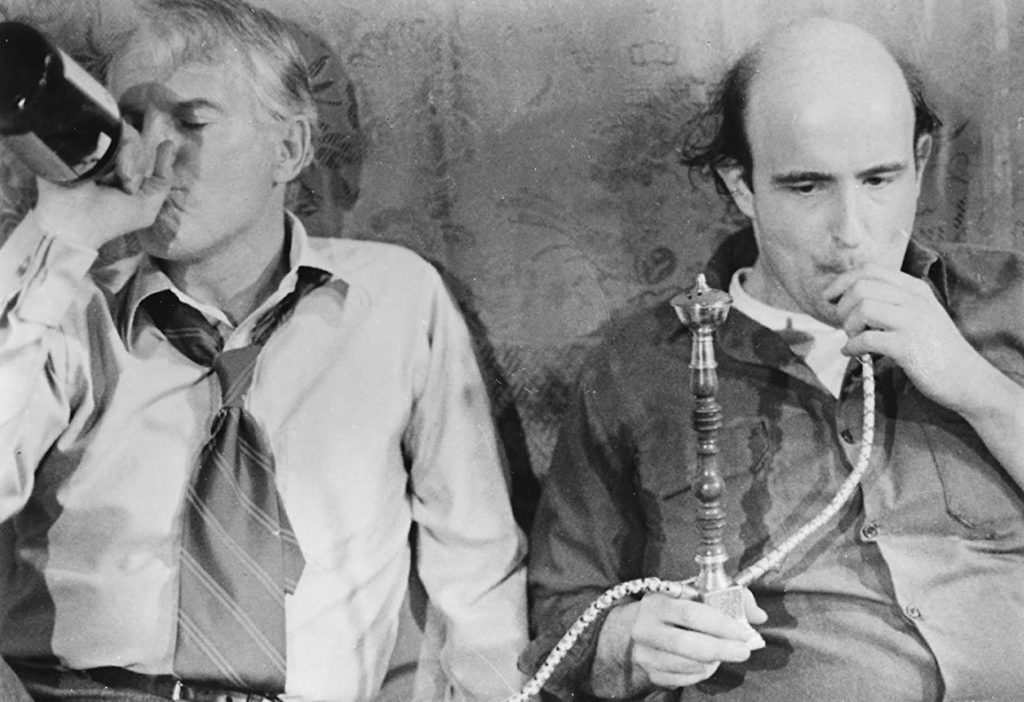

Directed by future Rocky and The Karate Kid helmer John G. Alvidsen, Joe centers on Bill Compton (Dennis Patrick), a Manhattan ad executive who accidentally murders his teenage daughter’s dope-pusher boyfriend after she OD’s on speed. Circumstances lead him to confide his crime to Joe (Peter Boyle), a hulking, loudmouth factory worker whose homicidal antipathy towards the younger generation makes him sympathetic to Bill’s plight. The self-loathing and lonely Joe blackmails the rich man into a tense, one-sided friendship, and after Bill’s daughter goes missing, he leads him on a search through New York’s hippie underground that ends in a horrific and blood-soaked tragedy worthy of the ancient Greeks.

As portrayed by the great Boyle (who also has a small, but memorable role in Taxi Driver), Joe served as the unbridled id of that era’s so-called silent majority, a walking torrent of nonstop, hateful invective leveled against minorities, women, liberals, and, most of all, “kids these days.” Joe’s effect on the traditionally mild-mannered Bill anticipates one of the most disturbing scenes in Taxi Driver, wherein Bickle picks up a deranged passenger (played by Scorsese himself) whose graphically unhinged, sexually charged tirade speaks to the cabbie’s own deep-set fears, desires and prejudices.

The effect transcended the screen: although Joe is clearly portrayed as a pathetic, revolting social pariah and ultimately revealed as a murderous psychopath, plenty of viewers at the time viewed him as the good guy. Nixonland, Rick Perlstein’s fiery chronicle of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, describes a moment shortly after the film’s release, where Boyle was approached by a kindly old woman at his neighborhood deli. She told him, “I agree with everything you said, young man. Someone should have said it a long time ago.” Boyle was so dismayed this type of reaction that, for a time, he swore off any role that had had him partake in violence.

Peter Biskind’s rollicking history of New Hollywood, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, describes a similar scene at the New York opening of Taxi Driver, which brought out lines of Bickle lookalikes who cheered loudly throughout the film, making it clear to the filmmakers that the central message had been lost “amidst all that blood and gore.”

Come the following decade, with the capitalist excess and nationalist fervor of the Reagan era in full ascent, Scorsese re-teamed with De Niro to make The King of Comedy (1982), a spiritual sequel to Taxi Driver in which De Niro plays Rupert Pupkin, a struggling comedian whose obsession with a famous late-night talk show host leads him down an increasingly dangerously path.

Although it lacks the visceral shock of Taxi Driver, swapping out that film’s suffocating air of despair and bursts of graphic carnage for a simmering unease resulting in moments of unbearable cringe, The King of Comedy is equally adept at conveying the way resentment over societal expectations manifest in the violent eruptions of lonely, socially awkward men with delusions of grandeur. Pupkin may not be a mass murderer like Joe or Bickle, but he is not far removed from them, and his specter can be glimpsed in the concurrent rise of reality TV and mass shootings in the decades that followed.

Though The King of Comedy is now regarded as one of Scorsese’s most prescient and unsettling films—it’s renown likely to increase thanks to its heavy influence on Joker, which sees the once-and-future clown prince of crime start out as a sad sack would-be comedian in the Pupkin mode (with De Niro cast as his TV talk show idol)—at the time of its release, it proved a giant commercial and critical flop. Much of its failure no doubt stems from changes in societal attitudes; it wasn’t that audiences had grown sick of characters like Bickle or Pupkin, so much as they were sick of seeing them presented as losers.

Thanks in part to the image of rugged individualism cut by America’s new movie cowboy president, the lone figure of violent retribution no longer represented the nation’s violent neuroses, but its ideal protector. The quintessential action heroes of that era—Dirty Harry, Paul Kersey, John Rambo—all of whom started out as morally ambiguous outcasts barely indistinguishable from the likes of Joe or Bickle, ended up the poster-children for rightwing dictates of law and order, their sneering contempt for both America’s underclass and at its liberal elite, making them paragons of Reaganite nationalism. Such promotion stood in direct contrast to The Searchers, which depicted the promise of the American experiment by way of its closing the door on such men of violence.

But as the country’s optimism floundered in the early ‘90s thanks to the unintended consequences of Reaganism—recession, war, labor crises, widespread racial strife epitomized in Los Angeles’s Rodney King scandal and subsequent city-wide riots, and a wave of public and workplace shootings—the anxieties of the post-war decades came back to fore. Once again, the angry white loner was an object of fear, even as more and more people began to sympathize with his plight.

This dichotomy is captured brilliantly in 1993’s Falling Down. The film follows Bill Foster (Michael Douglas), a recently downsized defense engineer attempting to make his way across Los Angeles to his estranged family on his daughter’s birthday, only to be continually harassed by a cross-section of then-current stereotypes—greedy Korean shop keeps, menacing Mexican gangbangers, snotty teen fast food workers, lazy panhandlers, lazier construction workers, smug corporate types and rich country club jagoffs—until he finally snaps, embarking upon a public rampage of increasingly deadly proportions.

Falling Down replaces the creeping dread and dank New York griminess of urban vigilante dramas with propulsive action set-pieces and the sunbaked menace of Los Angeles. The film’s dynamic (and often darkly funny) tone, combined with Douglas’s hypnotic turn as Foster—a figurative and literal square, his workaday attire consisting of boxy short-sleeve white dress shirt, marine buzzcut, and browline glasses, transformed by film’s end into a walking cruise missile—makes for an endlessly rewatchable piece of popcorn entertainment…which ultimately makes its diagnosis of the sickness that is white, working class resentment all the more frightening.

A scene halfway into the film, wherein Foster meets a neo-Nazi grotesque who, like Joe or Scorsese’s character in Taxi Driver, acts as a kind of shoulder imp for all his worst and deepest impulses, lays bare the fascist heart of said resentment. As the extent of Foster’s mental illness and history of domestic abuse are further revealed, any notion that he is simply an ordinary person pushed to his limit dissolves, and he is left exposed for the small, vicious, and dangerous man he is. Or, as he himself puts it during the film’s final showdown: “I’m the bad guy?”

* * *

Every generation gets their own version of this bad guy, regardless of whether or not they accept him as such…which brings us to Joker, the latest cinematic interpretation of undoubtedly the most popular comic book super-villain of all time. In it, Joaquin Phoenix stars as Arthur Fleck, a mentally-ill pushover driven to acts of private and public murder by the cruelty and capriciousness of the people and institutions around him (the film’s version of Gotham City standing in for Drop Dead-era NYC).

Along with Bickle and Pupkin, Fleck is partly inspired by Bernhard Goetz, the real-life New York mugging victim turned “vigilante” who, in 1984, shot and wounded four black teenagers in a Manhattan subway station. In Joker, Fleck’s first act of violence comes in the form of a subway shooting clearly meant to invoke the Goetz case, albeit stripped of any racial motivation (the victims in the film are a pack of thuggish white Wall Street bros).

Despite this literal whitewashing, the connection is apropros, given how it draws attention to the casual link between cinematic narratives about angry white loners and the infamous real-life cases to which they have parallels: the mass murder and “accidental” filicide committed by Arville Douglass Garland a few short weeks prior to the release of Joe; the near fatal shooting of Ronald Reagan by Taxi Driver obsessive John Hinckley Jr. (one result of which was Johnny Carson’s turning down the Jerry Lewis role in The King of Comedy out of fear the film might inspire future Hinckleys); the 2015 Chapel Hill shooter’s purported love of Falling Down. Goetz himself was often referred to as “Death Wish shooter,” in reference to yet another man-pushed-too-far movie set in ‘70s New York.

It’s important to recognize that most of these connections were either coincidental or incidental, or even outright false: a not small portion of the controversy surrounding Joker stems from the debunked rumor that the 2012 Aurora shooter was dressed as the character as he appeared in 2008’s The Dark Knight. Still, given how politicians and groups like the NRA love to lay the blame for mass shootings and other forms of gun violence at the feet of Hollywood, it should come as no surprise that pre-release apprehension regarding Joker has reached heretofore unseen heights.

Questions of the film’s actual quality notwithstanding, it seems impossible to deny Joker is the logical next step in the lineage of movies about the angry white loner. The precise admixture of fear and adoration its already inspired further highlights the extent to which the worldview of that archetype has become a full-fledged ideological movement, one that is now solidly entrenched within mainstream politics as well as mass-cult art and entertainment.

On the other hand, the fact the archetype has been so co-opted makes it equally hard to take said ideology seriously. After all, how can anyone identify as God’s lonely man now that the sense of social disenfranchisement, which heretofore defined their loneliness, has been turned into a literal blockbuster franchise?