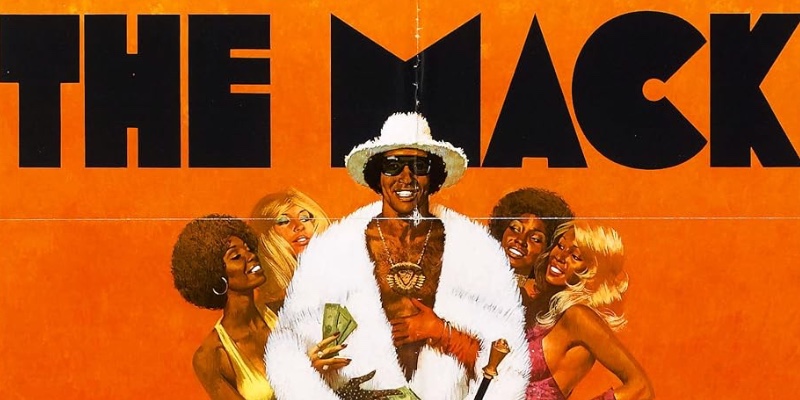

Spring, 1973. The orange-hued poster for The Mack hung in the lobby of the Tapia Theater for two weeks before the movie finally opened. As a fan of graphic illustration, from album covers to comic books, I was enticed by the image of a bold brother wearing a snow white fur coat, matching hat, shades and carrying gold handled walking stick. Flanked by a girl on each side handing him money and a gold colored Caddie in the background, the teaser text stated, “Now that you’ve seen the rest…make way for (large boxy letters) The Mack.”

A live-action Harlem version of the Fat Albert gang, my crew was a motley medley of black boys that included Kyle, Beedie, Marvin, Daryl and my little brother Los (who was called Perky in those days) we all lived in the same pre-war building at 628 West 151 Street. There was always a double-feature at the Tapia. Paying seventy-five cents at the door, the entire crew would troop in at noon and get lost in the cinematic sauce of krazy karate flicks, bugged-out American International movies about dogs robbing banks, an adorable killer rat named Ben and movies called Macon County Line, Grand Theft Auto and White Lightning. And, of course, there was the boogie of blaxploitation.

As a generation coming into our own, most of us separated from our fathers, we began to look at these so-called black action flicks films as the perfect Saturday afternoon surrogates for the men we didn’t have at home. Stepping into the theater, the gang walked across the hideous carpet, a multicolored nightmare covered with space-age designs and soda stains. An ornate chandelier (from the theaters more glorious past–when it was still called The Dorset) hung from the lobby ceiling.

After flirting with the pretty concession chicks while buying popcorn and Cokes, we rushed to the middle seats on the left-hand side of the theater. A mushroom cloud of reefer hovered over the theater. Simply breathing was enough to get you stoned. Yet, from the moment Max Julian’s sad face filled the screen, I observed a kind of existentialist indifference about the character Goldie.

Stepping out of prison into a world ripe with crime, this former car thief and drug addict soon reinvented himself as the coldest pimp in the Bay Area. Outside the few blocks that was Goldie’s entire universe, the rest of the world of was just part of the game on the road to fame. But as much as Goldie seemed to relish his reality, he still chided a small child who wanted to be like him. “I don’t ever want to hear you say that,” he scolded. Handing-out dollar bills, Goldie encouraged the kids to stay in school.

Slouched in my seat, sipping on a Coke, I was instantly seduced by this shadowy world of gambling spots, player’s balls, and the establishing of a stable of hot hookers I was intrigued by the image of Goldie training the chicks to shoplift and later putting them out on the hoe stroll.

Watching the black barbershop scene with rival pimp Pretty Tony, I was instantly reminded of the Shalimar, the Harlem barbershop where my stepfather worked, was filled with the same kind of badass sarcasm and player insight. The barbershop was connected to a bar of the same name, and both places catered to the colorfully dressed pimps in Harlem.

Twenty years later, The Mack became a classic signpost for pimping in pop culture, being an obvious influence on Snoop Dogg (on his debut Doggystyle he speaks lines of dialogue: “You ain’t no pimp. you a rest haven for hoes…”), Quentin Tarantino’s crazed white pimp character Drexl Spivey in True Romance (while watching the blubbery bare breast scene from The Mack, he says, “I know I’m pretty, but I ain’t as pretty as two titties…”) and countless other artists. However, the fact that at the end of feature “the mack” is penniless, motherless and hoeless, is never even mentioned by those who romanticize the pimp lifestyle of the film.

The Mack (much like Super Fly and Willie Dynamite) sould be seen as a cautionary tale advising against the dead-end world of crime, but for most viewers that significant message failed to penetrate their psyches.

“It safer to be a drug dealer than a pimp; at least a drug dealer doesn’t have to worry about a kilo of coke shooting him in the chest.”

–Ice-T

In the 1990s, the cult of pimpdom loomed large in the public imagination. From cartoons to cars, the Technicolor sparkle of Planet Pimp has spread like a virus through the psyche of America. Like drug addiction, some brothers just couldn’t say no. Regular men, who work nine-to-five jobs, were mystified by the pimp’s power, and awed by their personas.

Like comic Chris Rock pointed out in one of his routines, we want to know, “What do pimps say?” To this day, I find pimp poetics endlessly fascinating. In fact, the only other people I know who have as much voodoo in their verbal game are rappers, black homosexuals and preachers. As pimp laureate Iceberg Slim once said, “I sexed more hoes with conversation than I ever did with penis or tongue.”

In the minds of most men, the pimp aesthetic represented a sense of power without moral conscience. While we might understand that it’s wrong to slap a woman or place her in dangerous situations simply for the love of money, in pimp mode these rules of restraint no longer apply. To swipe a phrase from the title of writer Chester Himes’ autobiography, “a pimp’s life is one of absurdity.”

For the so-called “square” or “lame” fantasizing about The Game, there was a constant allure to the siren songs blaring from the battered jukeboxes stashed in the Black underworld. The problem with turning these desperado aspirations into reality is a matter of anger and viciousness. Without a doubt, the brutal behavior of a true pimp can be viewed as chauvinistic and misogynistic–although in player parlance, neither of these words exist.

A bona fide pimp isn’t about trying to get booty. He just wants to get paid. Most true pimps must have genuine hatred in their heart for the lame world and their own whores. Iceberg Slim told an interviewer from the Los Angeles Free Press in 1972, “The career pimps I knew were utterly ruthless and brutal without compassion. They certainly had a hatred for women.”

These days, the simplistic images of pimpdom perpetrated in the rap videos leads one to believe that all it takes to get a degree in pimpology is a gaudy goblet overflowing with designer champagne, the riotous roar of the latest rap soundtrack and a some bling-bling gleaming from their wrist.

“I made pimping a full time job, so bitches wouldn’t have to rob…”

–Big Daddy Kane, “Big Daddy Kane vs. Dolemite (1989)

With his big, black limo rolling through the sprawl of downtown Los Angeles in the summer of 2000, legendary rapper Ladies Love Cool J lounged in the buttery back seat. With L.L.’s muscles bulging and trademarked Kangol tilted to the side, he resembled a b-boy Adonis with a permanent smirk. L.L. moistened his thick lips with a quick wipe of his tongue, and became more relaxed than the mack, and just as cool.

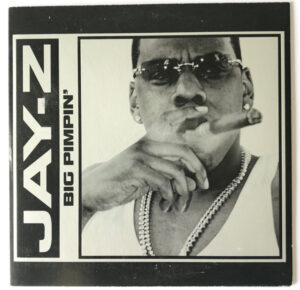

Dressed in a stylish crimson and ivory Fubu sweatsuit and white Nikes, L.L. clicked on the radio, and the piercing roar of L.L.’s labelmate Jay-Z erupted from the car’s speakers. As the post-bop bang of “Big Pimpin’” blared, L.L. nodded his cap-covered head and stared out of the window.

Yet, when the reining king of New York City recited the now-classic line, “Big pimpin’, we spending G’s…,” L.L. laughed uproariously.“If you ask me,” L.L said, laughed uproariously. “Jay-Z sounds like he is doing more tricking than pimping.

“Cavier and silk dreams, my voice is linen/Spittin’ venom up in the minds of young women.”

–Jay-Z, (Cashmere Thoughts, 1996)

It was a humid Indian summer afternoon in October, 1997 when I first hooked-up with Jay-Z. For months I had blasted his debut disc, Reasonable Doubt, inside my book-cluttered office. Feeling the cool sea of Jay’s complex storyteller-style splash against my earholes, I savored the brutal poetics and mean metaphors that described the drug rings, pimp dreams and player schemes of his hood.

From the hot ice of the brother’s voice and the buttery bop of his metaphors, we knew Jay-Z was a pimp before he even showed his true colors on “Cashmere Thoughts.” Much like my favorite ‘80s microphone fiend Big Daddy Kane (who was also an early mentor to young Shawn Carter–his real name) there was a genuine gritty humor and smoothness to his style.

Riding alongside Jay, one could almost imagine the young wannabe MC in his Brooklyn bedroom blasting Big Daddy (“…twenty-four sev chilling, killing like a villain,” he spat on the seminal single “Raw”) while absorbing the blaxploitation beauty of Kane’s lyrics. Kane set the foundation for future microphone macks. Perhaps what Jay-Z learned from those many hours of listening to Big Daddy Kane was how to lyrically articulate like a mack (whose affected speech patterns, if fused with the hard funk of James Brown/George Clinton/Rodger Troutman instrumentals, would sound like a song) without behaving like a minstrel.

As Jay-Z zoomed with me up Brooklyn’s notorious Myrtle (Murder) Avenue in a black Range Rover, I caught glimpses of the stark backdrop visuals that propelled his aural pimped-out persona: sweaty Bed-Stuy black boys playing basketball and clamorous corner-boys chugging cheap brew, older women tiredly dragging themselves (stooped shoulders, aching feet) from the subway station and pretty young girls pushing baby strollers down the soiled sidewalk, crack fiends fluttering in doorways and police sirens screaming in the distance.

Defining outlaw culture without glorifying the splashes of blood on the soiled floors of his native Marcy Projects or celebrating the cash/ champagne flow of gangster paradise, Jay-Z became rap’s first humanist hustler. “This ghetto is a part of me,” he said, turning down the radio. “But I refuse to record a song about people getting killed every two minutes. That’s not real. We have cookouts, family picnics and our friends. All of us are just trying to maintain our balance in the anarchy that surrounds us.

“When I was younger I used to be rolling up this block riding real slow and playing a Donny Hathaway album real loud,” he confessed. “I thought that was the coolest thing in the world, because it looked like a movie. You know, like a character from Scarface or The Mack.”

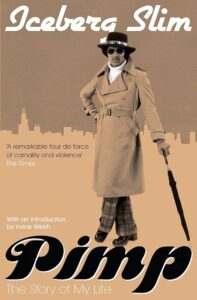

Moments after telling the story, he parked the ride in front of his former stomping grounds, Marcy Projects. Although he no longer lived there, his sisters still dwelled on the fifth floor. After greeting a few of his homeboys, including protégé Memphis Bleek, he directed me into the buildings dank hallway. Stepping into the stinky elevator that smelled of urine and reefer, Jay pressed the button and the doors closed. “You know, everything I come across in my life is used as material,” he said. “I would have to say the one writer that inspired me the most was Iceberg Slim.”

“…a pimp is really a whore who’s reversed the Game on whores.”

–Iceberg Slim (Pimp, 1969)

Nobody does a better mack daddy impersonation than Fab Five Freddy. “What’s up player?” he asks, his voice a cool growl. “Ain’t heard from ya in awhile player, hope you ain’t slacking in your pimping.” Once dubbed “the all-purpose art nigga” by his buddy Russell Simmons, the Bed-Stuy native (born a generation before Jay-Z or The Notorious B.I.G.) has been involved in everything from fine art to fine honeys, from filmmaking to breaking-beats. Next year his autobiography Everybody’s Fly (Random House) will be released.

Although the average rap fan might remember Freddy as the first face seen on YO! MTV Rap back in the golden year of 1988, his extensive resume includes working as a painter (alongside buddies Jean-Michel Basquiat and Keith Hering), directing rap videos (Gang Starr’s masterful “Just to Get a Rep” and KRS-One’s “My Philosophy”), producing feature films (New Jack City and Wild Style) and starring alongside Billy Dee Williams in a series of Colt 45 commercials.

While Freddy and I had been acquaintances for years, we didn’t become true friends until I’d seen him a few times at those off the wall Hot Cocoa parties in the late ‘90s. As I sat in the chair in the semi-darkened room waiting for the perfect baby-oiled booty, I’d spot the fashion-conscious Freddy rapping to some hot honey across the room.

At 6’2”, Freddy towered over the all of the girls and most of the guys. Wearing his trademarked sunglasses and hat, Freddy was as flashy as a riverboat dandy. “As a child growing-up in Brooklyn, I was inspired by revolutionaries, be-bop musicians and urban outlaws,” Freddy says, between puffs on his cigarette. “For me, these men were the foundations of coolness. They’ve become the models for everything I’ve tried to do in my career.”

In addition to the jazz cats that populated Freddy’s neighborhood during his formative years, he also met his first pimp when he was teenager hanging out on Reed Avenue. “A friend of my father’s was a dude named Paul Chandler,” Freddy remembers. “One day, he introduced to a real flamboyant guy who was wearing these tight clothes and dangling jewelry. At first I thought he was gay, but he said he was a pimp. Being a pimp wasn’t as popular as it is now, so I was a little confused at the time.” At the suggestion of Chandler, young Freddy popped into a local shop and picked-up a copy of Iceberg Slim’s first book Pimp.

Since that night in the early seventies, Freddy has had the opportunity to meet and speak with a few true players. “Every great pimp I met was proud of themselves, but they would all tell you they’d much rather be doing something else with their game. Iceberg was blessed he became a best-selling author, but that’s only one cat out of thousands.”

While Fab Five is a fan of Snoop and Jay-Z, he says, “The age of the true classic pimp is dead. That subculture exists more on records than on the streets. The pimps on parade one sees in music videos are far from the real thing.”

“Farewell to the night, to the neon light/farewell to one and all…”

– The Fall (an old prison poem)

Six months before his own death from cancer in the winter of ‘92, my stepfather Carlos Gonzales and I sat in his favorite Rican restaurant on 116th Street and rapped about old times.

Transformed from a neighborhood where King Heroin once ruled with an iron needle to a community now destroyed by crack (ten years later, gentrification would sweep the addicts into the East River while restoring the area to its former glory). El Mundial was one of the few remaining old businesses in East Harlem. Daddy had eaten at that spot since the early sixties, and all the waiters knew him by name.

“Hey Carl,” yelled Jorge, the restaurant’s chubby career waiter. He hugged Daddy’s frail body with macho affection. After seating us next to the plate glass window, Jorge bought us both glasses of homemade red wine.

Close to eighty years old, Daddy had lived life to the limit, working hard and playing harder, and was now suffering from bad health. Still, for his age, pop duke was a trooper. Regrettably, most of his Harlem friends had already gone to that Playa Playa Heaven in the sky. His old eyes, once so sharp, were now permanently bloodshot. His olive colored skin was pale, wrinkled and dry as sand. Dressed in a crisp white shirt embroidered with neo-deco designs, starched black slacks and black patent lather shoes, he sat stiffly at the table and buttered the warm bread.

“You know who I was wondering about?” I said. “Whatever happened to that pimp that hung out at the Shalimar back in the day?”

“Which one?” Daddy asked. After years of puffing filterless Camels, his voice was scratchy as broken glass. “There were a few of them, you know.”

“I was thinking about that dude Deacon Blue. You remember that cat, right? Everything in his wardrobe was blue.”

Sounding like a rusty crank on an antique Model-T, he laughed. “You still remember him, huh?” Staring out of the window as though wishing he had bottled some of his better days, a group of wild boys were shooting dice on a battered tenement stoop across the street. Black Sheep’s “The Choice Is Yours” blared at a vociferous volume. One cool Kangol-capped kid leaned against a wild-styled Rammellzee graffiti masterpiece and puffed a cigarette.

Even before Daddy answered, I was sure whatever had happened to Deacon Blue was not a happy ending. The inevitable ending of most cats in the pimp game is serving time in jail, being murdered by a jealous rival or taken-out by some coo-coo for Cocoa Puffs chick. Many others have destroyed their own flesh and spirit with drugs, and only a few live to tell the tale.

“Some people are better off getting a nine-to-five, because this pimp game can blow your mind,” Bishop Don Magic Juan once told me. “I know dudes in the game who just lost their minds. A pimp friend of mine from Chicago got so high on angel dust, he killed his own baby.”

Although Iceberg Slim claimed in a 1973 Washington Post interview that he had made attempts to save young men from the streets with his own examples of drug addiction and prison in Pimp, many readers simply ignored the less glam parts of the text. “It’s almost impossible to dissuade young dudes who’re already street poisoned, because without exception they have no recourse but to think they’re slicker than Iceberg,” he said.

“Last I heard, Blue was working as a skycap for American Airlines,” Daddy cruelly chuckled back at El Mundial. It was difficult to envision that once proud player president dressed in his dandy sapphire suits being forced to lug suitcases. Undeniably, like rapping, pimping is a young man’s art form. “Ain’t nothing worse than an old pimp,” Daddy said.