When the outlaw Billy the Kid (born Henry McCarty, also known as William Bonney) was gunned down on July 14, 1881, his legend was already on the rise. Within a year of his burial in New Mexico Territory, his killer, Pat Garrett, complained about the “thousand false statements” circulated via “public newspapers and… yellow-covered, cheap novels.” Over the next century, dozens of books and movies would muddy the actual details of the Kid’s life still further.

In “The Authentic Life of Billy, the Kid,” his book-length attempt at providing a “true” account of the outlaw’s life, Garrett wrote that McCarty was the “peer of any fabled brigand on record, unequalled in desperate courage, presence of mind in danger, devotion to his allies, generosity to his foes, gallantry, and all the elements which appeal to the holier emotions.” (His description might have been powered by a bit of guilt—earlier in the book, he frames ambushing the Kid as “unfortunate” and an “official duty.”)

Subsequent scholars have described McCarty/Bonney as a baby-faced ruffian and unrepentant killer. But whatever the truth of Billy the Kid’s life—maybe he was an illiterate psychopath gunned down at the age of 21, or maybe he was an all-American legend unfairly hounded by the law—it produced some great examples of Western and crime fiction. For 140 years, authors and filmmakers have used the Kid to illuminate all kinds of interesting things about America, redemption, and violence.

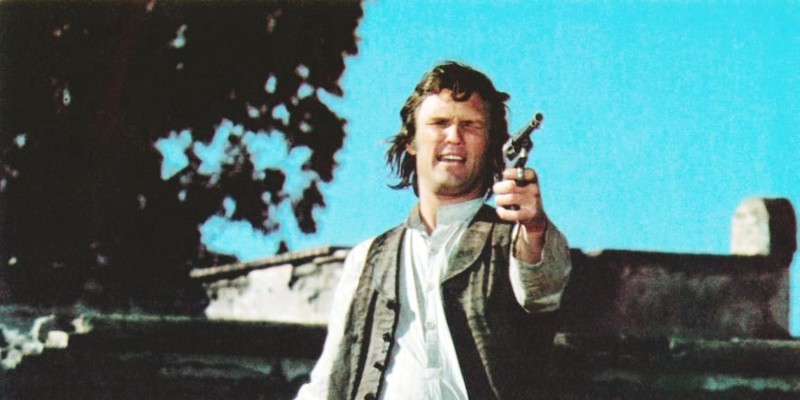

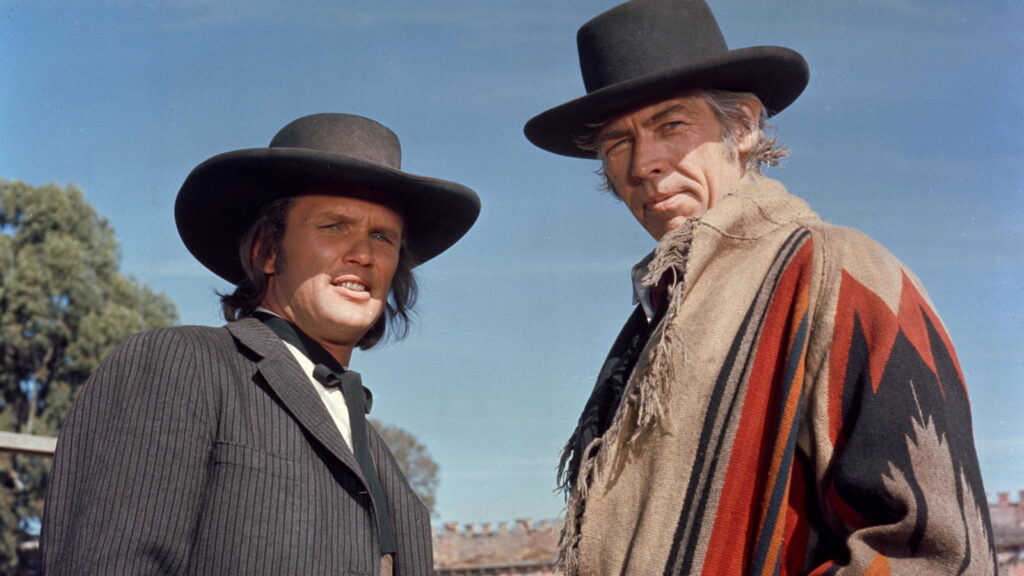

Outlaw as Anti-Establishment Christ Figure: “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid”

This 1973 film is a haunting, often elegiac retelling of the Billy the Kid legend. It’s also a hot mess at moments, its tone veering wildly from scene to scene, thanks in no small part to a troubled production and even more troubled post-production, intensified by director Sam Peckinpah’s deepening addiction issues.

Like “The Wild Bunch,” Peckinpah’s other revisionist Western, the plot of “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid” is powered by a schism between two former friends: Pat Garrett (a growling James Coburn), who gives up his outlaw ways to work for the government encroaching on the Western territories, and Billy the Kid (Kris Kristofferson), who shoots people in the back but nonetheless comes off as a beatific symbol of rebellion against a corrupt, often murderous system. At two points in the film, when Billy throws his arms wide in surrender, the allusions to Christ aren’t exactly subtle.

With its deep shadows and quiet Bob Dylan score, “Pat Garrett” often plays more as a Western Noir than a straight-up Western. In the end, Billy the Kid is probably the most honest character in the whole mess, because he never tries to pretend that he’s anything other than an outlaw and a rebel. The real Billy probably never saw himself in such grand thematic terms, but that’s why we have movies to nail these points home.

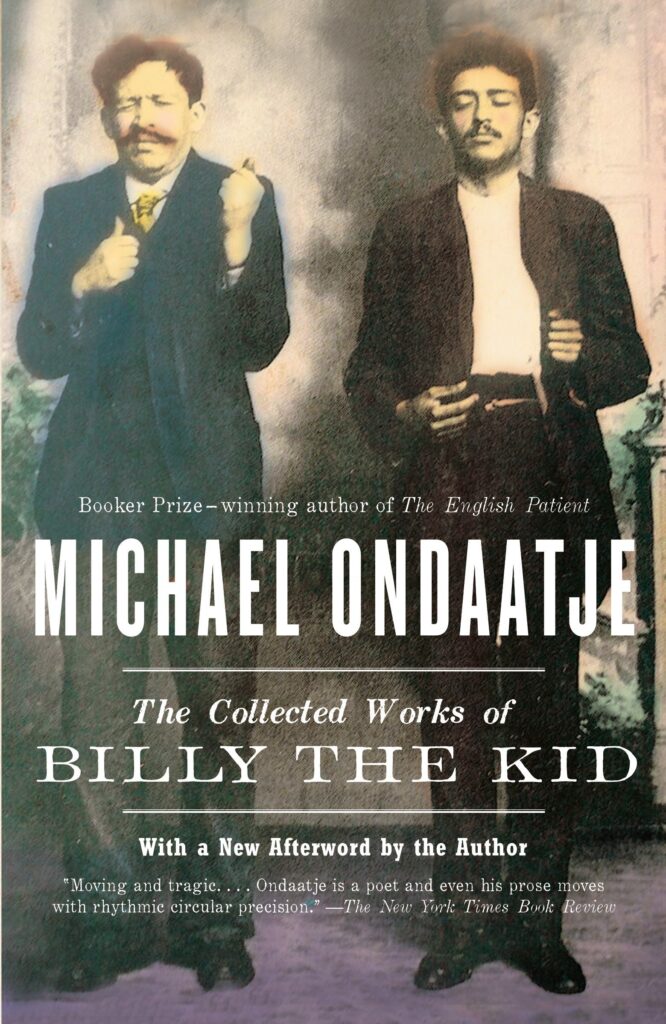

Outlaw as Poetic Muse: “The Collected Works of Billy the Kid”

Long before he authored “The English Patient,” a young Michael Ondaatje wrote a “verse novel” about Billy the Kid that mixed poetry, prose, interviews, and even contemporary newspaper clippings. Much of it takes place inside the Kid’s head, although the poetic stream of consciousness (“Blood a necklace on me all my life”) is likely nowhere close to what the actual McCarty was thinking at any given moment.

Readers familiar with Ondaatje through “The English Patient” and its dense, beautiful prose might be stunned by the stripped-down nature of “The Collected Works of Billy the Kid,” which reads almost like a Cormac McCarthy novel at moments; but the tone also perfectly mirrors the grittiness of the actual Western territories at the time, as well as the bitterness of the Kid’s life.

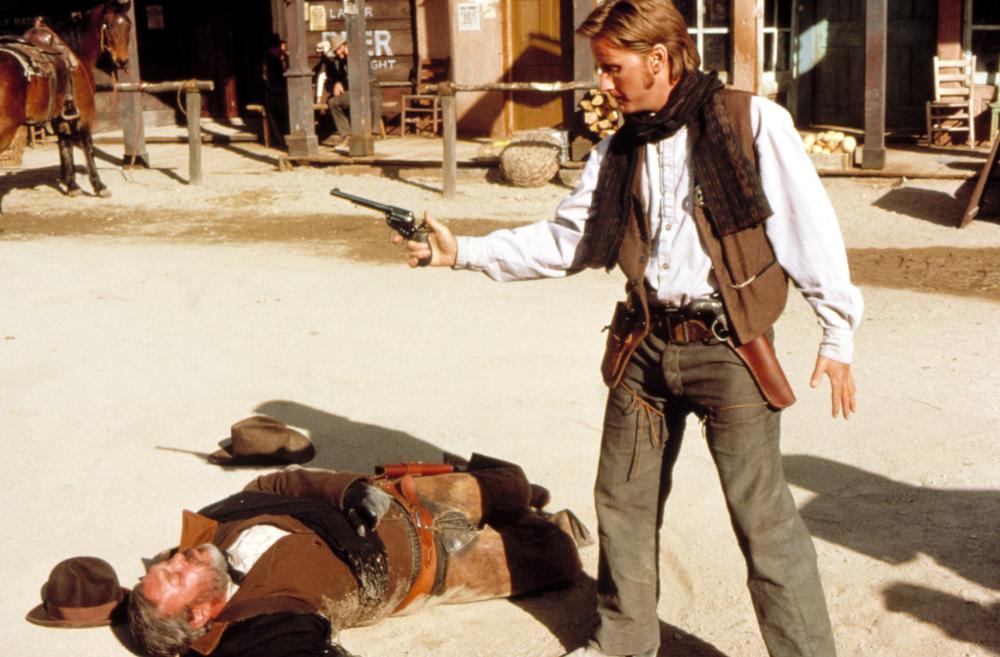

Outlaw as Teenage Heartthrob: “Young Guns”

This 1988 film managed to cast most of the so-called Brat Pack as participants in the Lincoln County War that helped make Billy the Kid famous, including Emilio Estevez as the Kid, Kiefer Sutherland as Doc Scurlock (one of the Kid’s friends, and a feared Regulator in his own right), and Lou Diamond Phillips as José Chavez y Chavez. It’s loud and cartoonish in that way of 1980s action films, but you’re not watching for the historical accuracy—you want to see young, charismatic stars blast a lot of bad dudes to pieces (including a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it cameo by Tom Cruise).

Like many young men, the historical McCarty might have seen himself as a charming and charismatic ruffian, the hero of his own story. At least in that sense, “Young Guns” presents the Kid as he would’ve likely preferred us to see him.

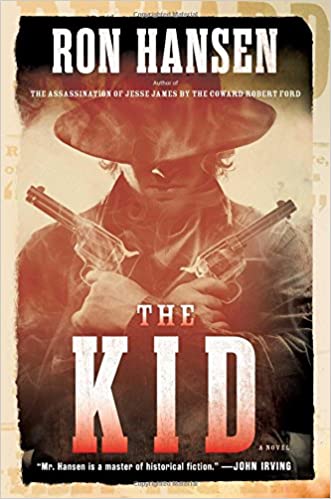

Outlaw as Literary Icon: “The Kid”

Ron Hansen, an author most famous for the literary western “The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford,” produced a novel about Billy the Kid’s life, aptly named “The Kid.” Like “Jesse James,” his Billy the Kid novel features hefty chunks of beautifully written exposition that almost come off as nonfiction, except the details are too rich—the historical record is too spotty, for example, to know when the Kid felt grief, or his wisdom teeth hurt.

But like Pat Garrett and many other writers, Hansen attributes purer motives to the ruffian’s actions. “And it was his undoing that in his aloneness and loss he fell in with a wild and vice-laden crowd,” the narrative relates. “Would have become an adored, happy, skylarking captain of all he surveyed had he not first linked up with miscreants like Sombrero Jack.”

As with his novel about the last months of Jesse James, Hansen expends a lot of energy into giving a killer outlaw a nuanced, often delicate soul. Does that align with the reality? We’ll never know, but Hansen did a lot of research into how the Kid observed his own growing legend. “He would have friends bringing him newspapers from all over New Mexico, and he would read about his life,” Hansen told NPR in 2016. “In fact, he would—on one occasion, at least, he wrote the editor of the newspaper, saying that this seemed to be figments of somebody’s imagination; I didn’t do any of those things.”

That doesn’t excuse the Kid’s actual acts of criminality, of course, which the book explains in detail. Hansen pulls off that trick of great crime fiction: he makes a criminal into a human and complicated figure.

Outlaw as Cringe: “Billy the Kid vs. Dracula”

It’s undoubtedly the dullest, cheapest attempt at bringing two cultural icons together in the same film. Everybody probably felt terrible about making it. You’ll feel terrible for watching it, even if you’re a bad-movie aficionado. Trust us on this one—the title is the best part.