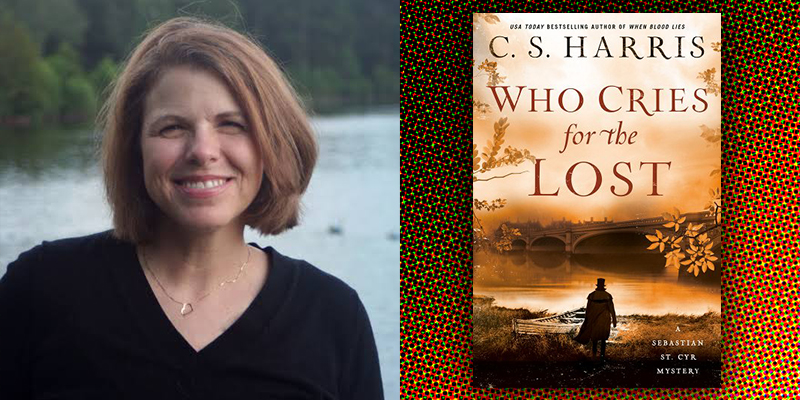

C. S. Harris is the bestselling author of the Sebastian St. Cyr Mysteries, set in the first decades of the 19th century, as well as several other series. Her research is impeccable, and what’s more, she captures the romance, energy, intrigue, and spirit of a chaotic time in British history. In her latest, Who Cries for the Lost, the wait for news about Waterloo is the backdrop to a complex murder mystery. Harris was kind enough to answer a few questions about her approach to historicals.

Molly Odintz: Who are some of your influences, when it comes to writing historical fiction?

C. S. Harris: I suspect most writers are heavily influenced by the books we read as children, and my favorites were adventure stories set largely in the Middle Ages and Renaissance or the nineteenth century: The Three Musketeers, The Prince and the Pauper, Huck Finn, Treasure Island, Kidnapped, King Arthur, Prince Valiant . . . you get the idea. I spent a chunk of my childhood in Europe, exploring castles and cathedrals and Roman ruins with my dad, a history professor. So I think those experiences, plus my own background as a historian, form a significant portion of the well from which I draw when I sit down to write. As far as more contemporary writers go, I still remember reading my first Ellis Peters Brother Cadfael book back in the 80s and being enamored of the idea of setting a mystery against a historical setting.

MO: What was your research process like for the latest book?

CSH: The research and writing process for this book was rather chaotic, in that I wrote the original proposal at the same time as I was starting to pack in preparation for moving house. I was still in the middle of packing and had barely begun writing when Hurricane Ida struck and heavily damaged our New Orleans-area house. We spent the next eight months driving back and forth between Louisiana and our new house in Texas, trying to salvage our belongings and get them shipped, and organizing the repair of the house and its sale—along with the sale of our lake house. So I was doing research in hotel rooms, in our half-wrecked old house, and in our half-painted new house. Some of my research material disappeared into boxes never to be seen again until after my manuscript was finished, but thankfully I had evacuated with most of what I needed hastily shoved into a bag. Ironically, I had gone through something similar after Hurricane Katrina with my third Devlin book, WHY MERMAIDS SING, so I knew I could do it. But please, world, never again!

MO: If you were going to travel back in time to any era, when would it be and why?

CSH: First of all, I would only want to travel back in time under carefully stated conditions, including guaranteed preservation of life, limb, and health! With that proviso satisfied, I would have a really, really hard time choosing. There are so many amazing lost things I’d love to see, from Petra in its glory days or pre-WWII Dresden to the American wilderness before the coming of the European conquerors. But there are also so many questions I’d like answered, such as what—of all the many theories—really caused the Bronze Age collapse, or what in the world happened to the Mary Celeste. But it would also be wonderful simply to go back in time and observe firsthand the rhythm of the days, to experience the sights and smells and sounds, to know firsthand what daily life was really like on the streets of Regency England, or in a medieval castle, or during one of the Journées of the French Revolution. How to choose?

MO: What’s next for Sebastian St. Cyr?

CSH: I’ve just finished writing #19, WHAT CANNOT BE SAID (coming in April 2024), which takes place shortly after Waterloo in July-August of 1815 and is set against the backdrop of Napoléon’s surrender and the agonizing British decision of what to do with him. The title comes from a fragment of poetry by Sappho, What cannot be said must be wept, so as you can guess, this book is about a dangerous secret. And now I’m just starting work on #20, which takes place in August of 1816, the “year without a summer.” It’s a fascinating period to explore because the weather was going crazy, and since no one had any idea what was causing it (a massive volcanic eruption), many people believed the world was ending. When you think about it, you realize just how terrifying that must have seemed.

MO: With recent Internet discussion of Master and Commander as a near-perfect film, I’d love to ask your opinion on the movie, and what you think is the essential appeal of the film and of its time period.

CSH: Admittedly it’s been nearly twenty years since I saw it, but I don’t think I’d describe it as a near-perfect film, even though they did a number of things brilliantly. The soundtrack is magnificent—I actually have it. And kudos to the producers for listening to their historical consultants (it’s so rare!) when it came to the myriad details of everything from ship construction, costumes, and surgical instruments to all the minutiae of life aboard 19th-century sailing ships, right down to the authentic sounds made by canon fire and grapeshot. That said, it’s odd that they then decided to ignore their historians and set the film in 1805, when the British and French (and Spanish) fleets were focused on what would be the big showdown at Trafalgar. I also have a hard time forgiving them for the climax scene, when—SPOILER ALERT!!!—Aubrey clumsily “disguises” his ship as a whaler to fool the French ship he’s been playing cat and mouse with all over the place. Impossible to believe that the French sailors wouldn’t immediately have recognized the Surprise by its profile alone, apart from all the glaring differences between a whaler and a Royal Navy frigate that a smudge pot really wouldn’t have disguised.

So those are my memories of the film: the riveting, authentic sense of life aboard a frigate; a charming peek at the Galapagos; and stirring music. And yet, despite my interest in the period, I’ve never been tempted to watch the movie again, and the reason is because the screenplay dragged in too many places. I’ve read several of O’Brian’s books, and while they are the “go-to” source for anyone wanting to capture the sights and sounds and jargon of sailing ships, they are not exactly tightly plotted or fast paced, either. So I understand why the producers felt the need to use parts of three books to construct their film. And yet they still failed to create a compelling story arc.

I’ve read that a prequel may be in the works, so I’m hoping for a better screenplay—joined to the same attention to accurate historical details.

MO: There are so many cameos from real-life figures in your novels. Do you have a favorite?

CSH: Honestly, I’d be hard put to pick a favorite. Undoubtedly the most colorful is Eugène–François Vidocq, the French criminal turned detective who appears in WHEN BLOOD LIES; he has inspired everyone from Victor Hugo to Edgar Allen Poe and Arthur Conan Doyle, and it’s easy to see why. But I also really enjoyed William Franklin (Benjamin’s son, in WHERE SHADOWS DANCE); the entire family was so fascinating and dysfunctional. And then there’s Jane Austen. I’ll admit I initially found the thought of portraying her in WHO BURIES THE DEAD somewhat intimidating, although in the end I actually enjoyed writing about her. In addition to reading a half-dozen biographies—there are so many!—I also reread all of her books and collections of her letters to make certain I captured her “voice.” I was never a huge Janeite (sacrilege, I know!) but after that experience I found I had gained a new appreciation for her. And of course, because of the role that Napoléon (mainly from a distance) and several members of his family have played in various books, I’ve done more reading about the Bonapartes than I ever would have otherwise. Another totally dysfunctional family, but definitely fascinating and entertaining.

***