Expatriate is a hard term to work with. In Europe it’s almost become an insult. No matter, for my purposes I’ll take it to mean those poor, unfortunate sods who reside in a foreign country or simply end up there exploited by intelligence services of one hue or another — or else they are powerless observers of a tragedy unfolding around them. They dot spy fiction like mothholes in a tweed jacket and for several books they seem to have been Graham Greene’s stock-in-trade … The Third Man (1949), Our Man in Havana (1958) — Wormold is probably the archetype of ‘unfortunate sods’ — and …

The Quiet American (1955); Viet Nam, not long before Dien Bien Phu. A book I have read several times since my teens and still don’t understand. In that sense it’s up there with The Great Gatsby, which I first read aged twelve. I remain baffled. Is the titular Aiden Pyle a good guy or a perfect fool? Is Fowler, the English narrator, reliable* or not? Are they in Viet Nam only to fuck it up? What is the ‘Third Way’? The start of US involvement? The overture to a tragedy?

(*Legnote: I wish there was a two-page pamphlet available for all reviewers explaining the concept of the unreliable narrator. It would make Nabokov easier to understand … fukkit even my books would be easier to understand.)

Lionel Davidson: Kolymsky Heights (1994); It’s a romp, a ride on a rollercoaster with a huge McGuffin, concerning frozen early hominids, that kickstarts the plot and then has very little to do with it ever after. The sort of device Hitchcock would use. To ask what the McGuffin means would be like watching Psycho for Janet Leigh’s heist.

Johnny Porter is a First Nation Canadian with an astounding grasp of the languages and dialects of Siberia and Alaska. The mission for which he is recruited is nonsensical. It’s not a book to take remotely seriously. No spoiler intended, but Johnny survives, and with more bullets in him than Warren Oates at the end of The Wild Bunch. Most memorable scene? In a cave in Siberia he builds a jeep out of spare parts he’s stolen one by one.

John le Carré: The Honourable Schoolboy (1977); This might be Le Carré’s best novel — it’s also his most complex. It sits between Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley’s People and resembles neither. It’s never been filmed and it’s not hard to see why the BBC chose to do it on radio (1983) rather than television — it would have cost the earth. Italy, Hong Kong, China, Thailand, all feature as locations. (I might add that the radio adaptation is deeply dull.)

The unfortunate sod of this novel is Jerry Westerby, quondam journalist and hesitant novelist, an ‘occasional’ pulled from a quiet life in Tuscany by Smiley. ‘The Hon’ really is his title, yet he comes across as aristocratic self-parody, calling everyone ‘sport’. And he has ‘a bit of a thing for damsels in distress’. In this, Westerby is much closer to the Bondish spy than he is to any other Le Carré hero. There is derring-do aplenty. His most memorable feature is his ‘buckskin’ boots, which cannot kick hard enough to get him out of the KGB/CIA mess into which the British drop him.

In his final collection of essays, The Pigeon Tunnel, Le Carré recalls meeting a ‘Jerry Westerby’ figure in the Raffles Hotel long after the book was published:

“I was standing face to face with a man I had created out of adolescent memories and thin air … so full of energy and dreams, so ardently British yet so identified with Asian culture …”

Build it and he will come? The collection also contains Son of the Author’s Father, a brief but fascinating guide to the psyche of the Le Carré protagonist.

Christopher Koch: Year of Living Dangerously (1978); Jakarta, 1965; “… in that era before the Vietnam war swallowed everything.”

You’ve seen the film. Who hasn’t? (So I’ll skip the plot summary.) Occasionally a film may improve on a book — Double Indemnity comes to mind — but good as Peter Weir’s film is (superb direction, Maurice Jarre score, stunning performance from Linda Hunt) the book is … er … better.

Koch had a wonderful gift for prose and a way of gripping the reader from the first sentence: “There is no way … of disguising the expression on your face when you first meet a dwarf.”

In Indonesia it’s the ‘Fifth Way’ that’s being sought. Makes me wonder what happened to the fourth.

Muriel Spark: The Mandelbaum Gate (1965) ; This novel is my list’s oddball. Muriel Spark may well be one of the strangest, most original novelists of the mid-century. A devout Scottish Catholic of Jewish descent, there was a devil of mischief in Muriel Spark. Most of her work is short, well-honed, spiky satire (‘elusive miniatures’ as the New Yorker put it) — there is something frightening about all her first-person female narrators in books such as The Girls of Slender Means (filmed by the BBC with the delicious Miriam Margolyes), A Far Cry From Kensington and more. But with The Mandelbaum Gate she broke her own mould — this novel is unlike any other in the Sparkopera — successfully; the book won the James Tait Black prize for 1966.

Jerusalem 1961; the unfortunates are Freddy, a diplomat who ought to know better, and Barbara, an innocent, sly self-portrait of the author, who drops herself in ‘it’ inviting the suspicions of both the Israelis and the Jordanians.

This is not an easy read. Perseverance pays. I suspect my focussing on the spookery rather than any issue of faith or identity would appall Dame Muriel, but this is a novel stuffed to breaking point with symbols, dualities, contradictions, deceptions and absurdities — the habitual Spark ingredients — and what better background could there be for a spy tale than one in which very little is to be taken at face value and no one to be trusted?

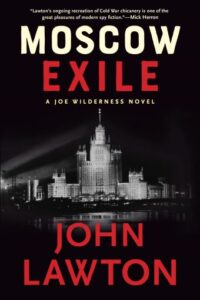

I’ve used the unfortunate sod plot only once, fully (The Unfortunate Englishman 2016), my utterly hapless Geoffrey Masefield. On reflection there’s a touch of it in my present novel (Moscow Exile — available from all good or bad bookshops on April 18th). Joe Wilderness is no innocent and agrees to be dumped down in Moscow for the money … but this is American money, the bagful of green moolah. Curiosity may well kill the cat; will the lure of the greenback kill the spy?

***