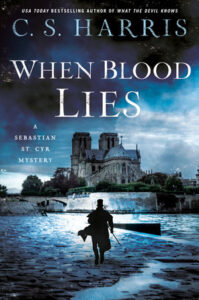

C. S. Harris, the pen name of Candice Proctor, is the author of the Sebastian St. Cyr novels, set during the Regency Era and featuring the dashing youngest son of a Viscount who inherits a title, and a wealth of responsibilities, after the death of his two brothers, all while solving plenty of crimes. C. S. Harris was kind enough to answer a few questions ahead of the release of her latest novel.

Molly Odintz: Regency Romances are all the rage again these days. What do you enjoy when it comes to writing a Regency-era sleuth?

C. S. Harris: Because I have a PhD in European history with the French Revolution and Napoleonic eras as my particular areas of focus, I knew I wanted to set my mystery series in that period. For many people, the Regency means balls and carriages and gorgeous filmy dresses, and there’s no denying that’s a huge part of its appeal. But it’s a fascinating age for so many other reasons. It was a time of tremendous change and stress. For much of the period, Britain was at war, with all the political unrest and economic pressures that entails. It was also a time that saw a huge societal shift, from the relatively free-thinking days of the late eighteenth century to the kind of severe, repressive mores that would come to characterize the Victorian era and the darkness of the dawning industrial age. So you have this narrow slice of time that was overshadowed by war and upheaval, and yet was at the same time so vibrant, so different, and filled with incredible people like Goethe and Beethoven, Ingres and Delacroix, Blake and Byron. It’s a wonderful setting for mysteries.

MO: You write romance as well. How does writing love stories compare to writing mysteries?

CSH: The romance genre today is very different from what it was when I first started writing. In those days I had the freedom to set my books anywhere from medieval France and colonial Australia to the Victorian-era South Seas. Some of my stories were pretty dark, and they were all solidly grounded in history. One of the reasons I switched from writing historical romances to mysteries was because my publisher wanted me to “pick a time and place and stick with it.” I decided if I had to do that then I’d rather write a mystery series. I love being able to explore a set of characters in more depth than is possible in one novel. With a series, I get to follow people like Sebastian and Hero, Tom and Gibson for years, and explore how events and their experiences change them. For a writer, that’s heaven.

MO: You’re a trained archeologist. How does your love of excavations make its way into your fiction?

CSH: I can’t say I deliberately set out to weave my fascination with archaeology into my books, but I know it’s there. One of the things I enjoy about this series is the way it enables me to explore historical London. So much of the city that Sebastian would have known simply isn’t there anymore. And in this latest book—WHEN BLOOD LIES—Sebastian and Hero go to Paris. I spent a year living in Paris while researching a book on the evolution of French thinking on the ideology of equality, so settling a novel in another city I love and in a time I know so well was a true joy.

MO: Sebastian St. Cyr is part sleuth, part spy. What about his character allows you to pursue different subgenres?

CSH: I knew I wanted my mystery series to explore all aspects of the society that existed in Regency England and not simply the familiar world of the haut ton. In order to do that I needed a character who was a part of the aristocracy so that he could move through the gentlemen’s clubs and ballrooms of Mayfair as an equal. But I also needed someone who was comfortable confronting danger, who wasn’t afraid to go down to the docks at night or into places like St. Giles, and Sebastian can do that. He spent years as a cavalry officer, and part of that time he served as an exploring officer. Most exploring officers simply rode around the countryside in uniform so they wouldn’t get shot as spies if they were caught. But some of them did more than that, disguising themselves as locals so they could slip in and out of enemy territory to get information that was needed. It wasn’t seen as a “gentlemanly” thing to do, so they didn’t talk about it. But they served a real function and some of them did do it. So Sebastian is a man who has that history and those abilities, which enables me to give my series the elements of action and suspense that it wouldn’t otherwise realistically have.

MO: I find it distracting when characters evince thoughts that are too modern for their time periods, yet I want historical novelists to capture the mindsets of their era without making us think that we should agree or sympathize with historical prejudices. How do you balance between the modern and the historical?

CSH: Every era has free-thinkers, people who don’t subscribe to the prejudices and superstitions of their day. Just as there are people today who believe that women should be subservient to men and that people with nonwhite skin are inferior, so there were people in the 18th and 19th centuries who dared to believe in the kind of ideas that we like to think of as “modern.” For a novelist, the trick is to be familiar with the true intellectual history of a period, to know what is and isn’t plausible, and to have your characters recognize when their thoughts and attitudes are out of step with the thinking of everyone around them—and suffer for it. I have been criticized by readers who insist that Sebastian’s attitudes toward race and gender are ahistorical. I just laugh and say, “Go read WOMEN, EQUALITY, AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTION, a historical study of the subject by Dr. Candice Proctor” (that’s the book I wrote after spending a year in the Bibliothèque Nationale and Archives Nationales in Paris).

MO: When it comes to craft, it can be a struggle not to get bogged down and to write only the details that enhance the narrative. What’s your advice to writers when it comes to putting just enough historical tidbits to ground the story, without losing the forest for the trees?

CSH: Even though I am a historian by training, I still do tons of research for each of my books. Only a fraction of that ever appears on the page. It helps me to craft my plots and visualize the scenes I will create, but most of that is behind the curtain—my readers don’t see it. When it comes to the particulars, I try to put in enough historical grounding that the story makes sense for readers who might not be familiar with the period. And I put in enough details to help create a sense of time and place without bogging down the action. It has to serve a purpose, or I leave it out.

***