It was 2006. Heartbeats by The Knife was raging through the plastic pores of our computer speakers as we thrust our legs into our American Apparel tights. My best friend Emily and I were preparing to go to Lit Lounge in the East Village. Emily was deliriously beautiful with long blonde hair and outrageously big eyes like one of those 80’s kitsch paintings. I was in art school. Emily was modeling, mostly paid in clothes which she’d pawn at Tokyo 7 for cash. It didn’t take long before she became a nightlife micro-celebrity. And each night we’d go out I’d hover in the background providing a chunk of shoulder or a blur of skin to frame her, watching as her image was sliced away, soon to resurface on party blogs.

2006 was the same year the iconic photograph was taken of Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan and Britney Spears jammed into the leather interior of a sports car leaving the Beverly Hills Hotel. It was also the year Facebook became available to anyone over the age of 13 and Twitter was founded. It was the final explosive and messy chapter of magazine power, before social media established an element of image control.

When I was out with Emily in New York bars, men’s eyes always cut like harpoons across rooms, necks twisting and shoulders shifting in her direction, but in the basement-club-scene of 2006 it was different; now it included party-photographers like Merlin Bronques who engineered images. Merlin would pose Emily with different girls in different situations; in bathrooms, on tables, back-stage, perched on bars, and he’d even, sometimes come over before going out to choose Emily’s outfit for the evening. Merlin was everything; paparazzi, stylist, and platform. And his images, while serving ample helpings of soft-core hipster porn, were ritually posted a day or so later on his blog Last Night’s Party, providing a drum-beat of FOMO under the moniker; Where Were You Last Night? Merlin Bronques was no Terry Richardson (an infamous industry predator with camera), but blurry question marks of consent still occasionally hovered; how drunk was the girl with her tits out?

When you see something that you shouldn’t you can always feel it. For me it manifests in a flip in the stomach. That wall collapsing between right and wrong, and the inevitable fact that it is too late—you have already seen it. You have participated in a photographic rape. This fizzing discomfort is a feeling I first discovered in my early pre-teen years from the upskirt paparazzi photos on magazine covers that stood in check-out aisles like perverse flags. And it is the same gasoline of Girls Gone Wild, the cousin of revenge porn and it is what propelled the socialite fireworks of the 00’s. The tabloid images of women from this era were provocations and somehow, always served with a chaser of blame; why weren’t these celebrities wearing panties? They were asking for it.

On one of my nights out with saucer-eyed Emily, Merlin Bronques took a picture of me bent over a toilet doing a line of coke. I was 19, drunk and high, and in that moment didn’t care, but the next morning I was visited by a conga-line of versions of myself that had been murdered with the impending publication of that image; politician-me, mother-me, professional-anything-me, my-parent’s version-of-me. But what bothered me most was I had been rendered a set piece in Merlin’s narrative. I had been transformed into what he needed, a girl performing the party. To his credit, Merlin, after my asking, never posted the image but the sinking feeling of it being released marked the beginning of my obsession with the venomous butterfly of an uncontrollable image, and the uneasy web of male-run platforms.

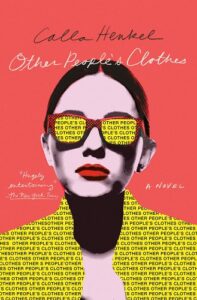

In my novel Other People’s Clothes, set in 2008, Hailey, an ex-teen model and one of the main characters, is driven by the need to try to control her own image. In writing the book, I came up with a silent origin story for Hailey’s obsession, stemming from a fateful run-in with a low-budget Terry Richardson; someone who under the guise of a professional setting, built a stage for Hailey to play a part she hadn’t fully agreed to. For me the true violence of this time-period’s images are how they were built. The industry which enabled this sort of American Apparel bedroom shooting where the girls were forced to make decisions under pressure with a camera already in their face. Back in 2011, a celebrity’s 21-year-old daughter on Twitter, wrote, “Last night Terry Richardson tried to finger me, I didn’t let him, obviously. But I did let him photograph me topless in a bathroom.” The celebrity’s daughter later claimed the tweet was satire, but either way it rings with the terrifying banality of a girl already compromised forced to set her boundaries in action.

It’s easy enough to imagine the entirety of Britney Spears’ life in the aughts congruent to being locked in the bathroom with a party photographer. The end-logic of this time period for Britney was death, and the tabloids nearly demanded it. Britney was harassed physically and mentally, while her body fueled the narratives supplied by the very machine that profited when she burned. So when Britney finally cracked, swinging her umbrella at the paparazzi with her freshly shaved head, it was nearly a Truman-Show-esque moment in which she was demanding to stop having to perform herself in parking lots, gas-station bathrooms, restaurant windows and leather interiored cars exiting the Beverly Hills Hotel. She simply wanted to get off the stage they’d built for her.

Now that we live in an era where Britney Spears is free from conservatorship, and is in control of her own Instagram, there is a mild sense of respite. And she is scooping her image like ice cream, posting a never-ending stream of selfies with paragraph-long captions riddled with emojis. She’s even posted nudes with small flowers covering her nipples, and a heart over her crotch with the captions like; free woman energy has never felt better. Britney, on her own terms, is comically serving us what we wanted; everything. But I still have a strange fizzing feeling when looking at her current images, something still feels wrong. Maybe because Instagram, the platform that supplies her an outlet to upload the photos she chooses, is yet another stage, with another sexist algorithm run by men. Or maybe because I’m still looking. And I just want to let her know she doesn’t owe it to us to perform a thing.

It is complicated to imagine how Britney, or any of these stars from this era, might truly regain control of their narratives and images. Does writing a book help? Did the dozens of documentaries help Britney? She didn’t think so. Did Ryan Murphy directing a limited series a la Monica Lewinsky help her? Maybe? But what is so shocking to me is that even in an era of cultural reckoning there is no reversing the cut of the original photographs. The theft is irreversible. The images are all still out there and flash with their original liquid violence each time they resurface.

***