In his eulogy of Caroline Blackwood, Jonathan Raban wrote that more than any optimist he’d ever known, “Caroline the pessimist made the world a happier place to be in because she could make mocking music of its terrors”. Indeed, her books are concise, mordant essays on evil. Similar in a way to Patricia Highsmith’s, but Blackwood has never garnered quite the same attention. Now that I’m familiar with her work, this bewilders me. Why isn’t Caroline Blackwood—rather than being obscurely referenced by Paul Thomas Anderson in an interview once—a household name, right up there with Shirley Jackson and Patricia Highsmith and all the authors Stephen King thanks for “building his house” in the Revival dedication page? Perhaps because she goes too far, perhaps because her stories are less snazzy, more real, to the point where it’s not funny anymore.

Whereas Highsmith’s characters (loathsome and unsavory in their own right) fight to change the predicaments they find themselves in—a somewhat hopeful trait, even if it is, more often than not, through murder—Blackwood’s characters refuse to do anything quite as implausible, preferring to stew in their decadent rancor and self-loathing. This is much less comforting for the reader, and much more depressing, because, I mean, isn’t this what we all do in real life?

While Highsmith’s novels center around elaborate crimes and often adhere to the reassuring tropes of the thriller genre, the crimes don’t really seem to be the point of the story at all for Blackwood. The Fate of Mary Rose, the closest thing to a thriller she ever wrote, tells the story of a little girl who is kidnapped, raped and murdered in an idyllic little village, but the focus of the novel, as described by the repellent narrator with excruciating unpleasantness, is the smothering, bordering-on-Munchausen-by-proxy devotion of his estranged wife to their sickly, joyless daughter, Mary Rose.

Blackwood’s magnificent works are like pure odes to odium, her prose cuttingly matter-of-fact. Averse to pathos in her writing, and allegedly also in her personal life, Blackwood would surely feel disappointed by any kind of sentimentality, of pity, from the reader, for her characters. Lady Caroline Blackwood, who was slim and beautiful and charming herself, who used cruel nicknames for her friends behind their backs, at first seemed to me utterly dedicated to humiliating the gauche and uncouth and overweight in her books just for the pleasure of it. Reading her scornful, bullying descriptions, one feels one quite wishes to please her, to agree with her and giggle along with her as one would with the popular girl in school who has just jeered at her latest victim and is waiting for you to join in. This is exactly what Caroline herself does in her short memoir Piggy, in which she teams up with the “porcine”, “freakishly overweight” school bully only to avoid his torment. I now wonder, then, if the author was actually using her cruel prose as self-preservation.

Blackwood’s claustrophobic novella The Stepdaughter, in which a New York housewife relentlessly vents the obsessive hatred she feels for her (overweight) stepdaughter through letters she writes to herself “in her head”, was believed by several of Blackwood’s acquaintances to have been based on her relationship with her eldest daughter, Natalya. Perhaps writing the book was Blackwood’s way of confessing, even exorcising, any guilt she felt over her troubled, neglectful mothering; after all, the villain of the story is clearly the stepmother, who comes to regret her behavior when it is too late, and if the reader feels sympathy for anyone it is for poor, wretched Renata, whose only sin is her passionate love of cakes. The Stepdaughter was published two years before seventeen-year-old Natalya died in the most horrific of circumstances—drunk after a party, she passed out, falling headfirst into the bathtub as she attempted to inject herself with heroin—leading one to wonder whether the supposed portrayal of her in the book had anything to do with her addictions.

If Blackwood felt any guilt over drawing from her personal life to write her fiction (to disastrous results), she didn’t relent. Great Granny Webster, a tale that opens with a young girl who is sent to live with her great-grandmother in a great, decaying country house, was based on Blackwood’s own family, her Great Granny Woodhouse allegedly just as unapproachable and miserly as her literary counterpart. The novel narrowly lost the Booker Prize when chairman Philip Larkin decided it was too autobiographical to pass as fiction.

Blackwood’s works delve deeply into complicated, ugly relationships between women, something that is especially fascinating when the author herself was defined throughout her lifetime by her marriages to high-profile men. Persistently, Caroline Blackwood is hailed through the ages as the ultimate muse—which is a disgrace. She should be hailed as one of the greatest, darkest writers who ever lived.

As the narrator of The Stepdaughter would sign off:

Yours in all bitterness,

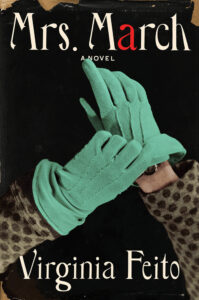

V. Feito

***