Edgar Allan Poe’s life and works have been widely dissected and analyzed by literary scholars almost from the first, that being his untimely, premature, and somewhat mysterious demise in 1849. Rufus Griswold, Poe’s executor, was that first, and his fiercely negative account set the tone for confirming and denying major biographical details and personality traits. The list of biographies and critical studies numbers in the hundreds. There will almost certainly be more written about Poe in the future.

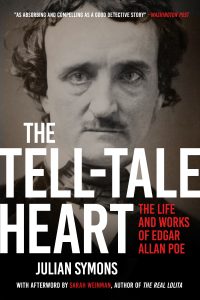

Which is why, when I was asked to write the introduction for Julian Symons’ The Tell-Tale Heart, originally published in 1978 and reissued by Sutherland House for the first time in more than four decades, I felt a fair degree of trepidation. What about Poe could Symons have possibly added that was fresh, that was, well, novel?

Quite a lot, it turns out. Additions that have far more to do with voice and perspective, and that also reflect and contradict key academic tenets of the late 1970s.

One realizes what a strange trip the reader is in with the opening sentence of Symons’ fiery introduction: “This book springs from a dissatisfaction with existing biographies of Poe.” Symons had so many gripes with earlier biographies. They were too trite, too boring, too concerned with symbolism and metaphor, too concerned with keeping faithful chronology of when Poe wrote what that his very life was obscured in the process. None of them, not even definitive door-stoppers like Arthur Hobson Quinn’s Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography (1941) or George Woodberry’s two-volume 1909 opus, met with Symons’ full satisfaction.

What Symons wanted was to untangle the Gordian knot holding together Poe’s tumultuous life and fragmented personality with his body of work, ranging from passable, even plagiarized, to outright genius. He decided the only way to do so was to separate Poe’s life and his work in discrete sections. As biographical strategies go it is strangely audacious, since, as Symons reflects in his book’s coda, “We are bound to ask, almost more urgently than of an other creator, how did this life produce this work? And what sort of artist was he?”

As Symons attempts to demonstrate, Poe’s work emerged from a life that created a “split man, a divided personality.” Poe could be “a wonderfully quick, intelligent and perceptive man, with a butterfly mind that never rested for long on a subject.” But he had a maddening ability to sabotage his own successes, to promise more than he could deliver—this was especially apparent in his varying relationships with and failed proposals to several women after he was widowed—and to attack, in print, those who could help him. Poe was a man afflicted by hubris, one who “intended to write down to the level of his readers, yet rarely managed it.”

Poe was a man afflicted by hubris, one who “intended to write down to the level of his readers, yet rarely managed it.”

This bifurcation, in Symons’ mind, could not be accurately reflected in a book that pushed together the strands of life and work, for one would cast a large shadow over the other and obscure what was really there. Never mind that work emerges from life, and the imaginative unconscious doesn’t work like Athena sprouting from the head of Zeus.

But the audacity of Symons’ project makes more than a bit of sense: because, he rightly argues in The Tell-Tale Heart, so much of what we think we know about Edgar Allan Poe is rooted in grudges, hearsay, rumor, and mystery, and of intuiting too much personal meaning from his successful, written-for-the-money mystery stories and from the poems that were closer to Poe’s heart and spirit.

***

Symons spends the first two-thirds or so of The Tell-Tale Heart on Poe’s life. He goes through the usual litany of calamities—the early loss of his father, disinheritance by his stepfather, John Allan, days at West Point, the marriage to his sickly 13-year-old cousin Virginia Clemm, his unhealthy relationship with drink, his premature death—and strips away myth to reveal Poe as a man of unresolvable contradictions. He could be the “Visionary Poe” capable of conjuring up poems like “the Raven,” and the “Logical Poe” turning to journalism and short stories to alleviate a consistent and desperate need for money. “The pressures of life, then, seem to have crushed the artist,” Symons judges. This is no gothic, spectral tale of otherworldly gloom but a more prosaic one of squandered opportunities and squalor, of romanticized ideals annihilated by the practical business of living in America in the 1830s and 1840s.

Then Symons turns his attention to Poe’s works, and the critical reception and analysis. He is largely sympathetic, albeit with a heaping dollop of skepticism, towards more psychoanalytical approaches embodied by the likes of Marie Bonaparte. He is far less kind with respect to most academic treatments of Poe, however, especially when they involve symbolism.

Symons takes special care to criticize the poet (and Candide lyricist) Richard Wilbur, who as “the founding father of the new Poe criticism” put too much emphasis on Poe writing “deliberate and often brilliant allegory.” This makes Symons blood boil, and he fulminates that Wilbur and subsequent scholars “do not read Poe so much as they read into him.” Rather than spend time seeing what one wishes to see, however convoluted, why not step back and consider what Poe actually wrote, and how he actually lived?

***

Julian Symons (1912-1994) was a prolific author of fiction, biography, history, and criticism, born and raised in Britain—younger brother (and later, biographer) to the writer A.J.A. Symons—before settling in America, where he taught at Amherst College for many years. Despite writing more than 30 well-received crime novels, Symons is not well-remembered anymore. And if he is, it’s likely for Bloody Murder, his delightful, essential survey of the crime genre first published in 1972 and updated several times thereafter.

Symons knew mysteries and thrillers better than almost anyone, save perhaps for Jacques Barzun, his peer in critical writing about crime fiction, and Anthony Boucher, the author and critic who contributed the bi-monthly “Criminals at Large” column to the New York Times from the early 1950s through to his death in 1968. Of course it makes sense Symons would reckon with Poe, just as he would later write critical biographies of mystery masters like Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Dashiell Hammett. And that, in his reckoning, Symons would arrive at the sense that Poe’s greatest achievements—his later poems, the ones that made him a literary celebrity before his untimely death—were “technically dazzling” and “also more than a little ridiculous.”

Those two descriptions of Poe’s work could also well describe Symons’ project. I came away from The Tell-Tale Heart feeling as if I had spent quality company with a thoughtful and voracious reader steeped in history and full of verve. Julian Symons writes with brio and fervor I found to be irresistible, even when I wasn’t certain I agreed with his argument and approach. And even he, after taking an entire book to separate out the life and works of Edgar Allan Poe, arrives the conclusion that “it is impossible to ignore his life in dealing with his art, because the two were impenetrably interwoven.”