Right after college graduation, my words weren’t ready yet. I hadn’t lived, not really. Though placed in the correct order and spelled correctly and ending correctly, those words read flat and were far from nuanced. Read aloud, those words didn’t sound like me—they sounded like Toni Morrison, Stephen King, Donna Tartt, and John Grisham. Hell, I didn’t even know what my voice meant. In my twenties, my vocabulary had been informed by Cosmopolitan and Glamour, “Draw me like one of your French girls,” and “Run, Forrest, run!” My parents were healthy. I was healthy, and my body acted the way it was supposed to act. I could eat what I wanted without fear of weight gain. My complexion was flawless.

My hair shone.

That all changed in my thirties. Ten years of holding my breath, of not knowing what mysteries my body would bring forth, not having the ability to describe my fear and frustration…those ten years gave me wrinkles. Those years made me sag, maybe not physically but psychologically, emotionally.

My voice, though, was being formed and honed by those hard words. I was learning, firsthand, of crafting pointed responses to women who insisted I breastfeed because “breast is best” and didn’t know that I wore a draining tube post-lumpectomy. I was learning, firsthand, of faking cheer and strength when all I wanted to do was cry and crawl into bed. My seams were being ripped, all things smooth pilling and my stuffing trailing behind me. A different woman now than the young thing who had big, bright eyes and a closet full of spandex.

Wrinkles and imperfections are good. Talk to an artist, and she will tell you that she loves drawing interesting, imperfect faces, old bodies with crags and scars. Actresses with unmoving faces—from too much cosmetic surgery or too much Botox—won’t land many acting jobs that require emotion.

A young writer just starting out may have something to say but may not have the wisdom to make that something interesting.

Ray Bradbury said, “If you want to be a great writer, then write a million words, and when you’re done, you will be.”

I didn’t know then what I know now: all of this—drafts, rejections, query letters, more drafts, dead stories, trunk stories— would help me learn how to tell a story for readers outside English professors and writing groups. Back then, I didn’t know that I had a while to go before hitting that millionth word.

“Unfortunately, the project you describe does not suit our list at this time.”

Throughout my treatment, the rejections came fast. I sent out queries even more quickly.

No. No. Not now. Not at this time.

I heard those words, and they came at me like lightning. But then, I learned more just as fast.

Editorial consultant, BRCA, remainders, low-fat diet?

I bought a mercedes-benz e350.

I had planned to buy this car with my big book advance or on my fiftieth birthday, whichever came first. At thirty-seven years old, though, I knew there was a possibility of never receiving that book advance or reaching that milestone birthday. My so-called gift with words would not help me obtain something I’d dreamed about since turning sixteen years old.

This car was a survivor’s gift. A fighter’s prize.

***

At this time, I also wondered, what else do I wanna do before my body wins and I’m forced to leave this world?

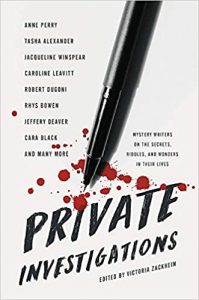

Write a mystery. A police procedural.

But I didn’t know how to write that world. Cops, robbers, dealers, murderers. Yeah, I’d lived around violence and anger, cops and dealers, gunfire and alley beat-downs, but I had no confidence in my ability to capture eighty thousand words of it.

I wondered, what else do I wanna do before my body wins and I’m forced to leave this world?Fear—of failing, of rejection, of not knowing—had kept me in place for so long.

After battling cancer and still being forced to stay in the ring, I understood and had experienced true fear. Ain’t nothing like signing consent forms acknowledging that you and your unborn child may not make it through the operation. Nothing like relying on a pill the size of a thought to keep cancer at bay. And it wasn’t as if I had a book contract. And at that time, it wasn’t as if I had an agent, either. No one to disappoint. I’d already self-published two rejected novels on Amazon’s Kindle platform. Could always do that with this police procedural.

What was the worst that could happen if I tried this?

What I wanted to happen was this: Terry McMillan meets Walter Mosley.

That’s who she’d be. But who was “she”? Didn’t know. Just . . . Her name was Lou.

I knew that.

And I knew that she was my survivor’s gift. She was my fighter’s prize.

“I love the voice and characters and enjoyed reading these pages.”

Jill, a literary agent in San Diego, wanted to read fifty pages. Then the entire manuscript. Then she called on the second day of February 2012 and said a word I hadn’t heard in so long.

Yes.

At that moment—and many moments after—I didn’t understand that simple yes. I searched for hidden meanings. Turned it over in my head, searching for burrs and weeds. Even today, I sometimes squint at “yes.” Keep one foot on the ground. Hold my breath. Refuse to enjoy the moment, to enjoy the “yes”

Because what does that word, a key to possible moments of joy for me, mean?

Words hurt. Words confuse. And I loved—and loathed—them.

Jill’s “yes,” though. It didn’t yank me, and I believed her. She’d love Lou Norton and my depiction of Los Angeles. Lou Norton, a native Angelena like me, who’d grown up working class. Lou had seen awful shit in her life and had straddled different worlds. She knew what it meant to hear gunfire with a brilliant blue sky above her, to see tall, swaying palm trees tagged with BPS or Rolling 60s. She had also sat in a booth next to LL Cool J at Roscoe’s Chicken N Waffles and searched the depths of her fake Gucci bag for the crumpled piece of yellow paper needed to get her clothes off layaway.

I had used my pain to create Lou—a homicide detective, she was empathetic, vulnerable, exhausted. A fully formed woman facing the sometimes impossible, a lady Sisyphus who makes it up the mountain only for that rock to careen down the other side and into her car. I didn’t give her sickness or disease to contend with. I didn’t want her traumatized by her body. I couldn’t be that cruel.

Jill would help me find a home for Lou Norton. She would find me another “yes.”

New words learned while on submission:

No.

Engaged.

Relaunch.

Track record.

Connection.

No.

On the day before my forty-third birthday, I completed my five-year Tamoxifen regimen. I’d done it—survived my battle with disease and survived my chemotherapy. No more mysteries except for writing them and learning more about this Lou Norton character. Two months later, though, my right ovary exploded, and my nine-year-old daughter found me writhing in pain on the bathroom floor.

This life, my life . . . The surprises would never really stop, would they?

What was gonna happen next?

What fresh hell was waiting for me in between writing stories and soccer/swim practice and Walking Dead episodes and playing Skyrim on my Xbox?

Lou’s first adventure of the two-book series would be published in just fifteen days.

Kristin, my new editor, made the offer for two books, and she had all the best words. Then they sold the UK rights, and I had a British publisher—

Titan UK wanted me to come across the pond for a tour.

This was happening.

Twelve years had passed between the publication of A Quiet Storm and Land of Shadows. My entire thirties had been traumatic and exhausting, with bursts of promise and joy. I would now have the writing career I’d fought for, with a body that had been cut up and restored too many times to count.

***

Kristin at Forge had just offered to purchase two more books for my now four-book series.

Lou would survive. I would survive.

Yeah, there would be more words to learn—oovectomy, abdominal adhesions, sudden-onset menopause, shopping agreement, no, not now, maybe later.

And credit-card bills and accumulated debt with so many surgery fees and imaging costs and…and…

Okay. Fine. This was my normal. I’d punch back.

I always punched back.

Most times with words. By refusing to surrender.

A scary, wonderful, messy life that bled past the edges of everything. A life that took in too much at times, that seemed unfair and strange and stupid. Lou, Miriam, Rikki, Stacy, Danielle, and every character I will write today and tomorrow help me unload some of this life, help me make sense of it all. And readers, not all of you but a lot of you, appreciate my words about this life.

Because your life may not be altogether different. Because you, too, have heard hard words, winced at their sting. You’ve shimmied and shimmered—until you’re grounded with strange, mean, uncaring words.

Uptight.

Stupid.

B****.

N*****.

C***.

A child of the church with musical ability, I was surrounded by song and melody. Alto in youth and school choirs. Violin player. Handbell ringer. Self-taught piano player. As an adult, my favorite religious songs had become more complex—from Jesus loves me, this I know to God with us, the living truth. Going through this…this strange, scary, convoluted journey, I needed gospel music, songs that spoke to my pain and fear and anger. And I listened to songs—Fred Hammond most times, “You Are the Living Word” and “No Weapon” and “I Will Trust” on repeat. Listened and sifted through the words for promises that I would be okay, that no weapon formed against me—even my own body—would prosper. On my drive to work, these songs infused me with hope, with promises that it would all work out in the end.

The end? What kind of end?

Those songs—powerful words made to be sung—on Fred Hammond’s albums still bring tears to my eyes. How his words ministered to me, how his words that played an active part of my healing prick me and shape me fifteen years after my obstetrician palpated that suspicious lump. I cry because I remember how I survived, how I climbed into my car each day and drove to work, pretended that I was okay, prayed that I’d be okay. Hummed those songs, Fred Hammond’s words beneath my breath as the room dipped into silence and I could hear the crunching of those bad words in my head.

Just a few months ago, I heard those words so many writers hear.

No.

Numbers.

Not right now. Sorry.

Months ago, those words broke me. I’d worked hard on a new story—I’d taken everything that I’d learned from writing the Lou Norton novels, the James Patterson story, the science-fiction short story, and the stand-alone seven-sinners novel and had created another interesting heroine with a twisting path and a smart mouth. After finishing, I was convinced that it was the best story I’d ever written, and I was certain that it would sell.

That afternoon, I cried in my office at work. Kept the door closed until my eyes whitened again, until my breathing straightened, until I could fake it.

Took about twenty minutes.

Later that day, as I drove my almost-fifteen-year-old daughter home, I shared with her my story of rejection. And as I talked to her, I cried again and told her that this hurt and that I was tired and that I couldn’t do more than what I’d done. I told her that I wished that I didn’t have to write, that maybe I wasn’t as talented as I thought. I told her that maybe I should find something else to do—she and my husband had given me a sewing machine for Christmas. Maybe quilting would be my thing now. Quilts are nice.

Nothing compared to finding new ways to use twenty-six letters to give body to a thought in your mind.After handing me a napkin to dry my eyes, my kid held my hand and said, “I’m sorry, Mom.” She kissed me on the cheek, then let me listen to Rachel Maddow’s show on the radio without hassle. When we got home, she disappeared into her bedroom to do homework. Her Intro to Comp and Literature class had just started Brave New World, and she’d already told me that the words and ideas in Huxley’s pages scared her. She was learning new words, too.

I cooked dinner because life went on. I told myself, while sautéing salmon, that I had experienced worse, that I’d published more books than the one book I’d prayed for. If I never landed a book contract again…My eyes burned—the thought of never landing a book contract again was not a new thought, but it was a thought that I hadn’t thought I’d think again, you know? Here I was, though, hours after rejection (again), cooking dinner (again) and wondering if my writing career was over (again).

Before bedtime, my daughter came to the den to say goodnight to David and me. Along with a kiss on my forehead, she also gave me a present: one of her new binders. She had printed out and glued past reviews and stars from my novels onto the binder. She’d written, “Don’t stop, Mom.” And I cried again—there were so many words that I’d forgotten. So many words I’d discounted. That night, after a brutal day, Maya had helped me to remember.

The next morning, I prepared for work. Dumped leftover salmon and potatoes into a plastic container for lunch. Gave the dog her dental stick. And then I grabbed a new notebook and a pack of pens from my storage bin. I had plenty of stories that needed to be written. So many things I had to say. Quilting was great, but writing…Nothing compared to a nice pen drifting over clean white pages. Nothing compared to finding new ways to use twenty-six letters to give body to a thought in your mind.

Words hold tremendous power—they shape lives, end lives. They set mood—on paper, in songs, in a conference room. We second-guess their meanings and their mysteries, and sometimes, we still do not understand.

I am now in the last year of my forties. I am still learning the meaning of lots of words, simple words. I am still remembering words, simple words.

Enjoy. Relax. Appreciate. Breathe.

Breathe.

_______________________________________