Featuring an exclusive excerpt from Carl Hiaasen’s new book

SQUEEZE ME, coming September 29, 2020.

___________________________________

As a crime and suspense editor, I noticed a trend in the submissions I began receiving in the 1990s. Comic noir was on the upswing, and the cover letter usually included a comparison along the lines of “you know, like Carl Hiaasen.”

But they were always wrong, and they still are. Sure, Carl Hiaasen’s novels are funny—sometimes laugh-out-loud absurd, sometimes so laceratingly sharp you have to check if your fingers are bleeding—but comedy is only their delivery system. Something else much more primal drives them: rage. Rage at corrupt politicians, greedy developers, corporate polluters, environmental desecrators, crooked lawyers, avaricious doctors, cheats, scoundrels, scam artists, zealots, and lowlifes of every description.

It’s that incendiary combination that makes Hiaasen’s books unique, why all attempts to duplicate him have failed. Oh, he has been compared to a lot of people. Among the writers he has been likened to are (deep breath) Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Joseph Heller, S. J. Perelman, P.G. Wodehouse, Evelyn Waugh, Mark Twain, Tom Robbins, Terry Southern, Dave Barry, Richard Condon, “Elmore Leonard on nitrous oxide,” and a combination of “the scrutiny of Tom Wolfe and the twisted imagination of Hunter S. Thompson” (The Wall Street Journal).

But he is an American original. In twenty books (so far!), including six for younger audiences, he has kept us grinning, while laying waste to the numbskulls, greedheads, and “whorehoppers” that beset us all.

The books are all set in Florida, because of course they are. Besides being the place where Hiaasen was born and raised, and lives in and loves, it is a place utterly unique in both its natural beauty and its level of venality. “Every pillhead fugitive felon in America winds up in Florida eventually,” muses a detective in Double Whammy (1987). “The Human Sludge Factor—it all drops to the South.” Another detective in Skinny Dip (2004), who is originally from Minnesota, concurs: “[In the upper Midwest] the crimes were typically forthright and obvious, ignited by common greed, lust or alcohol. Florida was more complicated and extreme, and nothing could be assumed. Every scheming shithead in America turned up here sooner or later, such were the opportunities for predators.” Tied to that, gloats a crooked (and entirely uncredentialed) plastic surgeon in Skin Tight (1989), “One of the wondrous things about Florida was the climate of unabashed corruption. There was absolutely no trouble from which money could not extricate you.”

In Carl Hiaasen’s books, a fugitive ex-mobster runs the Disney-like Amazing Kingdom of Thrills (Native Tongue, 1991), a TV evangelist builds a 29,000-unit development on top of a toxic waste site (Double Whammy), a congressman goes on a hushed-up rampage in a strip club (Strip Tease, 1993), a con artist and her ex-convict partner hurry to the devastation after Hurricane Andrew to work a personal injury scam (Stormy Weather, 1995), a newspaper magnate urges that “the easiest way to boost a newspaper’s profits is to cut back on the actual gathering of news” (Basket Case, 2002), a marine scientist pushes his wife off a cruise liner because he suspects she knows he’s been doctoring water samples on behalf of an agribusiness tycoon (Skinny Dip), a woman crashes her car while simultaneously driving and shaving an, um, intimate area (Razor Girl, 2016), a bipolar “queen of lost causes” turns the tables on a rude telemarketer by awarding him a free trip that will become a dire lesson in civility (Nature Girl, 2006), and a body double for an airhead druggie pop star (whose one hit, at age fifteen, was “Touch Me Like You Mean It” for Jailbait Records) is mistaken for the real thing and kidnapped by an obsessed paparazzo, who is himself about to run afoul of a 6’9” bodyguard with facial skin like Rice Krispies and a Weed Whacker instead of a left hand (Star Island, 2010).

Sound outrageous? Well, Hiaasen made up some of it. The car-crash personal groomer in Razor Girl? Actually happened. The congressional strip club fracas in Strip Tease? Happened. The fake plastic surgeon in Skin Tight? Based on an actual 1999 case (his victims had been too embarrassed to talk about it, his new patients never bothered to check beforehand). The personal injury fakery in Stormy Weather? All too true. The dead-sailfish scam in Bad Monkey (2013), the giant Gambian pouched rats in Razor Girl, the stolen-wheelchair entrepreneur in Strip Tease, the Hooters waitress on the payroll of a prominent Florida state legislator in Nature Girl, the man sexually attacked by a bottlenose dolphin in Native Tongue? These—along with the other regular reminders of corruption, excess, incompetence, and the creeping obliteration of nature—all part of the fabric of daily life in the Sunshine State.

Sometimes they get even crazier than the book. That incident in Strip Tease, for instance, was based on a congressman who got grabby at a topless establishment, but shortly before the movie version of Strip Tease opened, it was one-upped when the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Florida got drunk at an adult club and bit a dancer on the arm. Said Hiaasen, “It wasn’t the first time I felt plagiarized by real life, and it isn’t likely to be the last….It’s hard to stay ahead of the curve. Every time I write a scene that I think is the sickest thing I ever dreamed up, it is surpassed by something that happens in real life.”

The heroes that Hiaasen creates to deal with cases like this don’t tend to vary a great deal, at least most of the male ones. They’re either private investigators (Tourist Season, 1986; Double Whammy), ex-investigators (Skin Tight, Skinny Dip, Bad Monkey, Razor Girl), reporters (Lucky You, Basket Case), or ex-reporters (Native Tongue). They’re often cynical, adrift, disillusioned, but there’s something about the situations in which they find themselves that re-kindles their fire and awakens the romantic in them..

These characters work just fine, but they aren’t the characters you’re waiting for. You read Hiaasen for the audacious, feisty women; the extravagantly memorable grotesques; and the one character so beloved he’s appeared in seven of Hiaasen’s books. His name is Skink. He lives in the middle of the wilderness, subsists on roadkill, and wears a plastic shower cap and an electronic tracking device he found on a wild Florida panther. His graying hair hangs in braids, sometimes decorated with buzzard beaks; “his eyebrows, tangled and ratty, grew out at an angle that gave his tanned fact the cast of perpetual anger” (Double Whammy); and when one of his eyes gets knocked out, he replaces it with one from a stuffed barn owl.

Skink’s real name is Clinton Tyree. A college football star, Vietnam vet, and avid outdoorsman, “he won the governorship [of Florida] running as a Democrat, but proved to be unlike any Democrat or Republican that the state of Florida had ever seen. To the utter confusion of everybody in Tallahassee, Clint Tyree turned out to be a completely honest man” (Double Whammy). So the legislators and the developers worked around him, frustrating him more and more, until…he quit. Simply disappeared one day without a word and, with the occasional help of an old friend, a state trooper named Jim Tile who used to be in his security detail, he’s gradually become an environmental vigilante. He burns down the Amazing Kingdom of Thrills (Native Tongue), knocks out a vicious criminal with a tranquilizer dart and leaves him to the tender mercies of the Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge (Stormy Weather), kidnaps a real estate developer (Star Island), and in Sick Puppy (2000) cripples a hired killer and leaves him to die: “You’re dying even as we speak. Trust me. I know a thing or two about roadkill.”

He gets weirder as the books go on, too. In Skinny Dip, he’s prone to occasional hallucinations—a rattler with the face of Henry Kissinger, a rendition of “Midnight Rambler” as performed by Eydie Gorme and Cat Stevens—but he’s still a righteous force, even in the PG-13 version of himself in Hiaasen’s YA novel Skink—No Surrender (2014). He’s a character obviously very near and dear to Hiaasen’s heart— “He says and does things that lots of us wish we could get away with”—so it’s no surprise that there is a personal connection. One of Hiaasen’s best friends growing up was a boy named Clyde Ingalls, with whom he regularly had adventures exploring the swamps and wilderness around his boyhood town, and whom, a few months before their high-school graduation, committed suicide: “People like to put some political spin on poor Skink,” says Hiaasen, “but he has always just been my idea of what would have happened to Clyde if he had grown up.”

No such tragedy connects to the women in Hiaasen’s books, though—sharp, lively creations with minds of their own. “I’ve always liked strong female characters who were smarter than the men in their lives,” says Hiaasen, and he’s created a gallery of memorable ones: Kara Lynn Shivers, the Orange Bowl Queen in Tourist Season who proves surprisingly resourceful in the book’s big climax; Erin Grant, the exotic dancer of Strip Tease trying to make enough money to gain custody of her daughter while matching wits with powerful political and corporate forces; Lisa June Peterson, the executive assistant to the governor in Sick Puppy, hired for her looks, but able to run circles around the “lecherous, easily distracted clowns” around her; Joey Perrone, the wife pushed off the cruise ship in Skinny Dip, who, now that she’s “dead,” makes it her mission to gaslight her murderous husband; Merry Mansfield, the “well-groomed” title character of Razor Girl, who stays two steps ahead of everybody; Ann DeLusia, the celebrity body double of Star Island, who, when her employers wonder to each other whether she might be better off dead, has some decidedly different ideas about the matter, which she quickly puts into effect.

There are plenty of other such women in Hiaasen’s books, and they’re a pure delight—as are the extraordinary grotesque figures who haunt his pages, men hired to do the dirty work for the main miscreants, but who sometimes turn out to have a mind—even a heart—of their own.

Just a few examples: the 6’9” inch bodyguard I mentioned in Star Island, with the facial skin like Rice Krispies and the Weed Whacker? His name is Chemo, and his skin is the result of a freak electrolysis accident. We first encounter him in Skin Tight, where the ghastly uncredentialed plastic surgeon promises him a discount on dermabrasion treatments if he will eliminate some problems for him. Chemo does his deadly best, resulting in a murder conviction and seventeen years in prison. Now, in Star Island, having served his time, he has “walked out of maximum security and straight into a job selling home loans in Orlando. Because it was the peak of the real-estate boom and flimsy credit was abundant, the state of Florida bigheartedly overlooked all regulatory restrictions and welcomed with open arms absolutely anyone—including thousands of convicted felons—to the mortgage-peddling racket. Swelling the motley ranks were unreformed embezzlers, bank robbers, dope smugglers, burglars, pimps, counterfeiters, carjackers, and even a few killers.”

When the bottom of that market fell out, he was offered the job as the bodyguard for the airhead pop star, Cherry Pye, but she’s somewhat frustrating, because as far as he can see, this girl is as dumb as a box of rocks. Particularly irksome is her illiterate speech: “A Carmelite nun with whom Chemo corresponded in prison once sent him a book of basic grammar, which he practically memorized. His own speech wasn’t flawless, yet he tried not to butcher the language.” He buys a cattle prod and tells Cherry Pye that every time she says like, he will prod her ass. “Also on the list awesome, sweet, sick, totally, and hot.” She doesn’t believe him, of course. But that soon changes.

Then there is Thomas Curl in Double Whammy, likewise hired to eliminate some problems, though in the process, it is unfortunately necessary to kill a pit bull. Even more unfortunately, that dog, all sixty-five pounds of him, is latched onto his right arm, and immovable. Curl saws the body off, but the head remains, deteriorating as Curl goes about his nefarious business and starting to deteriorate himself, and he becomes fond of it, names it Lucas, starts talking to it: “You’re a good boy, Lucas.” It’s kind of sweet, actually….

What? You not a dog lover?

And no such rundown would be complete without the fabulous Bode Gazzer of Lucky You, the self-proclaimed “leader” of a white supremacist militia (membership: two): “Bodean James Gazzer had spent thirty-one years perfecting the art of assigning blame. His personal credo—Everything bad that happens is someone else’s fault—could, with imagination, be stretched to fit any circumstance. Bode stretched it. The intestinal unrest that occasionally afflicted him surely was the result of drinking milk taken from secretly radiated cows. The roaches in his apartment were planted by his filthy immigrant next-door neighbors. His dire financial plight was caused by runaway bank computers and conniving Wall Street Zionists; his bad luck in the South Florida job market, prejudice against English-speaking applicants. Even the lousy weather had a culprit: air pollution from Canada, diluting the ozone and derailing the jet stream.”

Bode is one of two lucky winners of the Florida lottery. When he discovers the other winner is black, however, he is convinced that it is all part of the government conspiracy to keep “Christian white men” from winning the lottery, and sets out to steal the other ticket. He succeeds, but in an ensuing fracas on a small island in the Keys, succeeds also in inadvertently kicking a napping stingray, which promptly pierces his femoral artery with its barb. Bye bye Bode, we hate to see you go.

At the end of it all, however, it all comes back to Hiaasen’s core: his love of Florida’s natural wonders, his awe at its beauty and endless variety…

All of these characters—heroes, villains, and hangers-on alike—are captured with a journalist’s pinpoint eye for detail, and a gift for the throwaway line or observation. A kidnappee is thrown over a shoulder “like a sack of tangelos” (Tourist Season); a sad zoo, Sheeba’s African Jungle Safari, consists of “one emaciated lion, two balding llamas, three goats, a blind boa constrictor, and seventeen uncontrollably nasty raccoons” (Double Whammy); a woman keeps her deceased parents “in a Sears industrial-size deep freeze…perfectly preserved beneath three dozen Swanson frozen dinners, mostly Salisbury steaks” (Strip Tease); a one-and-done character is introduced, “Mae’s father was a retired executive from the Ford Motor Company, and was almost single-handedly responsible for ruining the Mustang” (Sick Puppy); so are two New Yorkers running a bar in Key West, “At first they were distrusted because of their sobriety and competence, but in time the locals accepted them” (Razor Girl).

At the end of it all, however, it all comes back to Hiaasen’s core: his love of Florida’s natural wonders, his awe at its beauty and endless variety:

“A light sea breeze nudged the boat across crystal shallows, past eagle rays and lemon sharks and an ancient loggerhead turtle, half-blind and thorned with barnacles. It was a perfect afternoon.” (Bad Monkey)

“At every bridge the water seemed a different shade of blue. The winter sky was bright as an egg, and spangled with birds. Yancy loved the evocative roll call of the lower Keys—Big Coppitt, Sugarloaf, Cudjoe, Ramrod, Little Torch. Here was one blessed stretch of the highway that hadn’t yet been blighted.” (Razor Girl)

“This is my church, this island out here and all the others—so many islands that nobody’s counted ‘em all. And the sky and the Gulf and the rivers that roll out of the ‘glades, all of it’s my church.” (Nature Girl).

* * *

How did Hiaasen come to worship at the church of Florida? He was born to it. He grew up in Plantation, Florida, a small suburb of Fort Lauderdale, “literally on the edge of the Everglades. There wasn’t a mall, a strip mall, not anything, [just] cow pastures and wetlands. After school, I’d get on my bike, go snake-hunting or fishing, just hanging out and exploring.” Most of that is obliterated now—the dirt road down which he biked is an eight-lane highway. “It is a very difficult thing for a kid to watch that unfettered part of your childhood being paved before your eyes.”

In high school, he started a satirical newspaper called More Trash, which he wrote and handed out himself in the halls. “It was really just a smart-ass rag, but the cool kids who never spoke to me would stop me and tell me how funny it was. I remember the administration of the high school wasn’t very happy, and I liked that, too.”

From there, he went to Emory University, where he contributed a satirical humor column for the school newspaper, and wrote his first uncredited book, though few people know about it. Hiaasen was 17 or 18 when a doctor on the faculty at Emory named Neil B. Shulman asked for his help as a ghostwriter. “He just had a big stack of papers and said, ‘I want to make this a book.’ I didn’t know if Finally: I’m a Doctor was even going to be published. When he called me a couple of years later and said Scribner was going to publish it, I was blown away.” A later book by Shulman, What? Dead…Again? would become the movie Doc Hollywood, starring Michael J. Fox.

Finally in 1985 [Hiaasen] received a column of his own at the Herald—one that he has maintained ever since, and which, according to him, at one time or another has pissed off just about everybody in South Florida…

After two years, Hiaasen thought that rather being an English major, he wanted to join a journalism program, and he transferred back home to the University of Florida, where he wrote for their newspaper, too, now mixing humor with outrage. After graduation and two years with a local paper, in 1976 the Miami Herald came calling, and he worked his way up from the Broward County bureau to the city desk to the Herald’s investigative team (winning two Pulitzer Prize nominations along the way) and finally in 1985 received a column of his own at the Herald—one that he has maintained ever since, and which, according to him, at one time or another has pissed off just about everybody in South Florida, including his bosses. “People say sometimes, gosh, that was brave of you to write such-and-such last week. ‘Brave?’ What do they mean, ‘brave?’ It’s right! How could you not write it? Sure, it would be easier to write a funny story about something the dog dug up in the garden…but I told my editor, the day I do that, put a bullet in my brain.”

It was at the Herald that his editor and friend Bill Montalbano suggested they sit down together and write a thriller based on Hiaasen’s pieces about Colombian drug gangs and their assassins in Florida (“There was a lot of violence in Miami then. It was before Don Johnson showed up in his Armanis.”).

The result was Powder Burn (1981), a “good, solid underworld melodrama,” in the words of Kirkus Reviews, soon followed by another strong thriller, Trap Line (1982) and a novel drawing upon Montalbano’s work as a bureau chief in Beijing, A Death in China (1984). Those were excellent books, still well worth reading today, but gave no hint of what Hiaasen would become (“Those books were much more in Bill’s voice than Carl’s,” his agent said later), and Carl remembers the collaboration in those pre-word processor times as chaotic (“We were working on typewriters. We were literally cutting and pasting and gluing papers together and using Magic Markers”).

Then, in 1984, he approached his book editor with an idea for a novel of his own about a group of eco-warriors intent on driving the tourists out of Florida. It was called The Orange Bowl Solution, but when the editor said he loved the idea, but not the title, Hiaasen changed it to Tourist Season. The book made an immediate impact—nobody had ever seen anything quite like it before—and a few books later, Hiaasen made it to the New York Times bestseller list, a position every novel of his has kept ever since. Hiaasen’s adult and kids’ books have won nearly a dozen honors since, his journalism has brought him four of the most prestigious awards in that field, including the Ernie Pyle Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Society of Newspaper Columnists, and his books have been published in 34 languages, “which is 33 more than I can read or write.”

There hasn’t been a new adult book since 2016, though. “There’s an obstacle to my kind of writing if you have a lot of stuff going on in your personal life,” he has said. “I think it’s a particular obstacle if you’re trying to be funny and the stuff in your life isn’t particularly funny.” That was the case in 2018, when in June of that year, a man with a vendetta came to the office of the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland, and killed five people. One of them was Carl’s younger brother Rob, age 59, a columnist and assistant editor.

The great crime writer Laura Lippman had been a colleague of Rob’s for about ten years at the Baltimore Sun, and she said this in a piece in the New York Times: “There are so many ironies about the shooting in Annapolis, and the lives of five talented, dedicated people— people who loved their job and the community they served—cut short. But the irony that sticks with me is that Rob would be the perfect person to write about the suspect. And he would do it with abundant empathy and curiosity….He was determined never to look down on anyone….He had a keen sense for the kind of human-scale stories that resonate with everyone.”

Carl’s latest kids’ book, Squirm, and a piece of nonfiction were both already in the works and published that year, but that was it. However, I am pleased to report to CrimeReads fans that a new Hiaasen adult novel, Squeeze Me, will be published on September 29, 2020—and at the very end of this piece, you’ll find the first pages, along with a few words from the author.

You won’t be disappointed—and you won’t be surprised to find references to real-life contemporary events and personalities.

Beyond what Carl and Knopf have supplied here, I don’t know anything more about the book, but you can be sure it will create the kind of reaction that Donald Westlake had to Strip Tease. He praised Hiaasen for “bringing us in fiction the unpalatable truths that nonfiction is too polite to mention, and doing it hilariously, his harsh judgments and cold-eyed observations wrapped in so many comic bells and whistles that your sides hurt after a while, just from reading.”

Or, in the words of Dave Barry, “It’s a good thing he’s able to write books and kill bonefish or else he might be an ax murderer. And a good one. And a likeable one.” (A note from Carl Hiaasen: “My friend Dave is obviously not (and would never claim to be) a fly fisherman. Bonefish are always released alive.”)

___________________________________

The Essential Hiaasen

___________________________________

With any prolific author, readers are likely to have their own particular favorites, which may not be the same as someone else’s. Your list is likely to be just as good as mine—but here are the ones I recommend.

Tourist Season (1986)

“The recipe for redemption is simple: Scare away the tourists and pretty soon you scare off the developers. No more developers, no more bankers. No more bankers, no more lawyers. No more lawyers, no more drug smugglers. The whole motherfucking economy implodes! Now, tell me I’m crazy.”

That’s Skip Wiley, star columnist of the Miami Sun, but also secretly El Fuego, the leader of a small group of domestic terrorists calling themselves Las Noches de Diciembre, though to the group’s despair, when the paper reports it, they’re called Las Nachos de Diciembre. “This is your brilliant publicity coup!” screams one of them. “We are now world-famous nachos!”

The screamer is Jesus Bernal, a homicidal ex-member of the anti-Castro group, the Seventh of July Movement (though its members couldn’t really remember if the day they were naming it after was July 7th or July 6th, and ended up calling themselves The First Weekend in July Movement). The other two members of Wiley’s group are Viceroy Wilson, a broken-down pro football player turned anarchist, and Tom Tigertail, a wealthy bingo-hall Seminole intent on launching the Fourth Great Seminole War.

You could say they’re not all exactly on the same page—but that doesn’t mean they don’t create havoc, staring with the body of the president of the Greater Miami Chamber of Commerce found floating on the Pines Canal packed into an apple-read Samsonite Royal Tourister, with a 79-cent toy rubber alligator stuffed down his throat. Other acts of mayhem follow, all culminating in the planned kidnapping of that most cherished of Florida figures, the Orange Bowl Queen.

“By the time we’re through, old pal, Marge and Fred and the kids will vacation in the fucking Arctic tundra before they’ll set foot on Miami Beach,” Wiley proclaims. Not if reporter-turned-investigator Brian Keyes has anything to do with it, however, or homicide detective Al Garcia, or, for that matter, Kara Lynn Shivers, the Orange Bowl Queen herself

All the ingredients of the classic Carl Hiaasen novel are already all here in Tourist Season, packed in as tightly as a body in an apple-red Samsonite Royal Tourister.

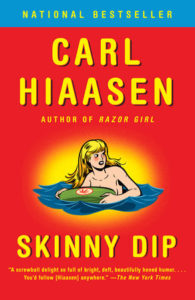

Skinny Dip (2004)

“I had a feeling he didn’t love me anymore, she thought, but this is ridiculous.”

That’s Joey Perrone, the woman pushed off the cruise ship by her dirtbag husband. Fortunately for her, she had been co-captain of her college swim team. Even more fortunately, she is found clinging to a floating bale of marijuana by Mick Stranahan, a one-time investigator for the State Attorney’s Office who was compelled to retire several years ago when he shot and killed a crooked judge (to be fair, the judge tried to shoot him fist, but still…). Now, he’s living in a house on a small island, by himself, which is just as well, because he has six ex-wives.

“It’s true,” he tells Joey, “six ex-wives is nothing to brag about.”

“At least none of them tried to murder you.”

“One came pretty close.”

“Really? She go to jail?”

“Nope. Died.”

Joey’s husband, Chaz, had been doctoring water samples for a mega-farmer named Red Hammernut, who’s been dumping fertilizer into the Everglades, but once Chaz suspected Joey was on to him, he figured he had no choice but to dump her, too, literally. Now that she’s still alive, though, she has no intention of disabusing him.

“’And this is so you can disappear to someplace far away, right? Fake a new name. Start a new life.’

“’Oh no,’ Joey said. ‘This is so I can ruin him.’”

At first, she just messes with his head a little, moving things around in the house, leaving traces of herself in the bedroom, cutting her face out of a photo, but soon it’s time to get serious with considerably more intricate and sophisticated acts of revenge. It’s working, too – all too well, because it makes Chaz Perrone’s sugar daddy mighty nervous that he’s unraveling, and he sends out a man named Tool to babysit him. Tool is 6’3”, 280 pounds, with a head like a cinder block, but just because he looks like a goon doesn’t mean he can’t think for himself. And what he’s thinking is…something’s very fishy around here….

And that’s when the real trouble starts. Lots of twists and turns, a fabulous feisty woman, a superb grotesque, and an immensely satisfying ending. What more could you want?

Bad Monkey (2013)

“On the hottest day of July, trolling in dead-calm water near Key West, a tourist named James Mayberry reeled up a human arm.

“’Well, son,’ the captain said, ‘We’re in the memory-making business.’”

Andrew Yancy is a former detective reassigned to restaurant inspection—the “Roach Patrol”—after very publicly sticking the business end of a vacuum cleaner up the bottom of his lover’s husband. He admits that it was not his finest hour. The sheriff doesn’t want that arm cluttering up his county, so he orders Yancy to take it to Miami, “because Miami was the floating-human-body-parts capital of America,” to see if it matches someone there. And with that, a cavalcade of events starts tumbling over one another: assaults, murder, drive-by shootings, insurance scams, real estate fraud in the Bahamas, sex criminals, voodoo curses, and a foul-tempered capuchin monkey so vile he was fired from Pirates of the Caribbean.

Sound like a lot? I haven’t even gotten started. I haven’t mentioned the hurricane, the hired thug named Egg with ears like fetal fruit bats, the assistant coroner fond of sex in the morgue, the swarm of bees, the retired cocaine smuggler, and the agent from the Oklahoma State Bureau of Investigation. Not to mention what really happened with that severed arm.

You’ll love all of it.

___________________________________

Book Bonus #1: Fiction, and Some Personal Notes

___________________________________

Here’s when I let you know that the editor who told Hiaasen that The Orange Bowl Solution might not be the best title in the world…was me. I edited all three of the Hiaasen and Montalbano collaborations (actually, it was Montalbano and Hiaasen—Bill was the senior member of the team), and Carl’s first three breakout books, Tourist Season, Double Whammy, and Skin Tight.

I loved working with both of the guys, but as I mentioned, there was no indication that Carl was going to burst out into such a radical new direction until I received a package from Carl’s agent, Esther Newberg, in May 1984. Attached was Carl’s cover note to Esther, which began, “This bulky stack of printouts comprises nine chapters, although I’ve got a feeling it’s either too much, or not enough, for me to send off. I apologize for not having it typed, but if you don’t like it, I’ll probably just throw it away anyway, so I wasn’t ready to invest in a typist….Let me know if you think it’s worth showing to Neil.”

She thought so indeed, and thought it was great, though my boss was a little more circumspect. I have his note right here: “This is a book to be careful with; as you know, the tongue-in-cheek tone is a tough one.” (He wasn’t the only one. You know what Publishers Weekly said? “Miami Herald columnist Hiaasen writes with a seriousness of intent and knack for characterization which, unfortunately, outstrip his comic talents. This is an auspicious solo debut for the serious Hiaasen…but a lukewarm one for him as a potential comic-absurdist.” Bzzt, wrong.).

In any case, I made a deal for the book, but very shortly thereafter, before there were any contracts, I was wooed away from my then-publisher Atheneum, where I’d published the collaborations, to G.P. Putnam. One of the books I took with me, with the approval of all concerned, was Tourist Season. (I guess Atheneum was still being careful). After several rounds of edits, I got the final manuscript from Carl in April 1985, with a typical Carl type of note—“Well, it ain’t Elmore Leonard, but I sure hope you like it”—and we were off.

The problem, as I mentioned at the top of this piece, was that it wasn’t like anything else anybody had ever read—and it was my first novel on the Putnam list. I knew I needed some quotes. People like Robert B. Parker, Pete Hamill, John Katzenbach, and John Godey, author of The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3, pitched in, but the quote I was proudest to have received was from John D. MacDonald, the grandmaster of Florida crime fiction: “Carl Hiaasen gives outrageous events such an edge of plausibility and believability the whole book is vibrant and alive. He is a wicked observer of frauds and foibles. The prose style is deft and effective. He makes Miami Vice look like Terry and the Pirates.”

MacDonald died not long after that. It was one of the last quotes he ever gave.

“Carl’s house, where he lived with his wife and son, was literally a four- or five-minute walk away. I used to stroll over there, and we’d talk book stuff and he’d show me his snakes—he kept a lot of snakes.”

I enjoyed working with Carl, of course, but there was an extra fillip to our relationship: My in-laws lived in Florida. My wife and son and I went down to see them every year during the winter break, and not only did they live in Florida…they lived in Plantation. Carl’s house, where he lived with his wife and son, was literally a four- or five-minute walk away. I used to stroll over there, and we’d talk book stuff and he’d show me his snakes—he kept a lot of snakes. One day, we leafed through a bass-fishing catalogue hoping to find a title for the book tentatively called Fish Fever we’d be publishing the next year, when I stopped and stuck my finger on a page—“this one.” It was a fishing lure called the Double Whammy.

For various reasons, Carl ended up decamping to Knopf after Skin Tight, but we kept in close touch, and then in 1996, I got a chance to work with him again. The Herald had gotten the idea for their Tropic Sunday magazine to have thirteen South Florida crime writers do a serial novel. Each writer would do a chapter and pass it on to the next one, who’d read whatever had been written so far, add a chapter, and then pass it on again. It’s an idea that has since been done many times, but it’d only been tried once before at that point, by a bunch of Long Island reporters, for a book called Naked Came the Stranger.

So the Herald’s was called Naked Came the Manatee. Dave Barry wrote the first chapter, and Elmore Leonard and Carl wrote the final chapters, except that Leonard ignored the rest of the text entirely and just did his own thing, and it was up to Carl to try to make some sense out of the motley collection of material in front of him and bring it all to a satisfactory conclusion. His work collaborating with Bill Montalbano had to have helped him. I appreciated his efforts all the more, because I bought the book rights, which meant that out of the once-a-week episodic Tropic publications, I had to do what I could to make it work as an actual coherent book. There are stories to tell about that, but let’s just say some of the writers had taken their assignments more seriously than some of the others, and leave it there.

It was a pleasure to work with Carl again, though, and Putnam started contemplating the actual publication of the book. I called him up and said, “I know you have no obligation to the project other than the chapter you wrote, but if we were able to get some really solid media opportunity, would you be willing to do some promotion?”

He said yes, and added, “And you should check with Dave and Dutch Leonard, too.”

“But I don’t know them,” I said (though I later would know both, and even publish several books with Dave). “Try them,” said Carl. “I bet they’d be game.”

I did, and the three of them agreed that if we didn’t split them up, but let them be a unit, so they could just have fun, they’d actually give us a full week! Two memories stand out from that time. The first was when People magazine decided to do a photo shoot. When the three authors walked into the studio, they found themselves for some reason confronted with an array of beach toys as props and a large empty wading pool. Carl shook his head and drew Dave aside: “We can do this—because we have no pride—but we can’t ask Dutch to go along with this.” But when they turned around, there was Elmore Leonard, happily sitting in the pool, already playing with the toys. The photos came out great.

The second memory is of the dinner we all shared in New York. Great Greek food, plenty of wine, and a lot of wonderful jokes and conversation. This was the first time I’d met either of the other guys and it was like I’d died and gone to heaven.

And as it turned out, the three of them did such a great job of conveying how much fun they were having that it was contagious with the media. We got terrific coverage, and the book ended up not only selling, but missing the bestseller list by only a single slot, which was a far better result than anybody had ever expected from this antic project.

Carl and I have continued to stay in touch since then, and there is one more postscript. Bill Montalbano had left the Herald and gone on to a very distinguished career with the Los Angeles Times as their bureau chief first in El Salvador, then in Argentina, Rome, and London. One day, Esther Newberg came to me with an idea he’d had for a thriller based on his Rome experiences, which would feature a Pope with revolutionary ideas, a cabal out to weaken him, and a past that has the Colombian cartel out to get him. It was called Basilica, and we published it in 1998. Shortly before pub date, though, I got a call from Esther. It was about Bill. He had been walking down a London street, suffered a massive heart attack, and died. Words cannot express what all of us felt.

Basilica was an excellent book and went on to get wonderful reviews. “A rare and powerful book,” said PW. “He has left behind a memorable legacy.”

___________________________________

Book Bonus #2: Young Readers and Nonfiction

___________________________________

Hiaasen’s six books for young readers so far have been Hoot (2002), Flush (2005), Scat (2009), Chomp (2012), Skink – No Surrender (2014), and Squirm (2018), all of which became bestsellers, four of which won honors, including a Newbery Honor for Hoot. The genesis for them was simple. Hiassen had a stepson who was eleven, and nieces and nephews about the same age, and he thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to write a book that I could give them without getting taken away to the Division of Family Services?”

Hoot came right out of his own childhood—a novel about bulldozers coming in to level the ground where a rare species of burrowing owls lived in order to build a development, in the book’s case the latest chain restaurant of Mother Paula’s All-American Pancake House. “In west Broward County, near where we lived, there was a lot of open acreage, and it was purchased by a company that was going to build a condominium. The next thing we know there were bulldozers and backhoes, and they cleared the land where these little owls lived, these burrowing owls, and they just buried them alive. That pissed me off then, and it pisses me off today.”

It features a middle-schooler named Roy Eberhardt, a tomboyish girl named Beatrice Leep, and a mysterious Skink-like barefoot kid known as Mullet Fingers. “Ever since I was little,” the kid says, “I’ve been watching this place disappear—the piney woods, the scrub, the creeks, the glades.” Together, they do something about it—at first, just tearing the surveyor’s stakes out of the ground and scattering them, the way Hiaasen and his friends did at the condominium site, and then escalating. The finale reaches a climax at the groundbreaking ceremony, attended by the company’s chief honcho, the press, protesting students, and an actress playing Mother Paula, all leading to a fair amount of clean-cut mayhem and a highly satisfactory resolution.

The other books follow suit, as enterprising youngsters and their adult sympathizers take on a casino boat dumping sewage into the ocean, a wannabe Texas oilman threatening Florida’s most endangered species, a bogus reality survival show which threatens everything it claims to be celebrating, and a poacher stealing eggs from the turtle nests at Loggerhead Beach.

“I get thousands of letters from all over the world from those who connect utterly with the characters and what they stand for,” says Hiaasen, “in a way that suggests they have a much greater awareness at eleven or twelve than I did.”

As for the nonfiction, Hiaasen has six books. Three of them are selections from his Herald columns, Kick Ass (1999), Paradise Screwed (2001), and Dance of the Reptiles (2014). He says he publishes them to prove he doesn’t just make up all the sick stuff in his books. “His columns, like his fiction, reveal Hiaasen as a crystalline, pitiless seer of human weakness,” said one review of Kick Ass. Exhibit A from that collection: “Miami is the best place in America to be a criminal. It is to hard-core felons what Disneyland is to Michael Jackson.”

Speaking of which, 1998 saw the publication of Team Rodent: How Disney Devours the World, a short but memorable examination of Disney’s effects on the environment and local culture. It isn’t pretty. One example: “The absolute worst thing Disney did was to change how people in Florida thought about money; nobody ever dreamed there could be so much. Bankers, lawyers, real-estate salesmen, hoteliers, farmers, citrus growers – everyone in Mickey’s orbit had drastically to recalibrate the concepts of growth. Suddenly, there were no limits. Merely by showing up, Disney had dignified blind greed in a state pioneered by undignified greedheads. Everything the company touched turned to gold, so everyone in Florida craved to touch or be touched by Disney. The gate opened and in galloped fresh hordes. The orange groves and citrus stands of old Orlando rapidly gave way to an execrable panorama of urban blight.” The book ends with an unforgettable investigation into the death of a rare black rhinoceros in Disney’s Animal Kingdom. “I’m perhaps the only man you have ever met who has pictures of a rhino necropsy stashed away somewhere.”

The Downhill Lie in 2008 chronicles Hiaasen’s ill-advised return to the sport of golf after a “much-needed” 32-year hiatus. And 2018’s Assume the Worst: The Graduation Speech You’ll Never Hear, illustrated by Roz Chast, is, well, just that—a litany of life’s challenges, obstacles, and inanities, ending with a glimmer of hope: “One thing happiness is not,” writes Hiaasen, “is overrated.”

___________________________________

Movie Bonus

___________________________________

“Lots of screenplays have been based off my novels,” notes Hiaasen, “but only Strip Tease and Hoot were actually made into movies.” Why so few? As Andrew Bergman, the screenwriter and director of Strip Tease has said, “Carl Hiaasen’s books are difficult to get right. The characters are so extreme and the situations on the page are hilarious, but as scenes they are grotesque or too violent or logistically too difficult.”

Strip Tease came out in 1996 as a vehicle for Demi Moore and featuring Burt Reynolds in a Newt-Gingrich hairpiece as the politician obsessed with her. The critics were not kind (they were right), but Hiaasen insists that the scene featuring Reynolds slathered from his neck to his toes in Vaseline is “one of the high points of modern American cinema.” Elsewhere, he’s said, “I thought it was pretty funny. I can’t complain. They kept the Vaseline scene, the cockroach scene, and the snake scene. That’s my contribution to culture this year.”

With Hoot in 2016, “I got more personally involved, because it was for kids and I know that kids are meticulous readers and they also have great expectations when they go to the movie theater. So I got a lot of notes from the studio and tried to make things right, but in the end it’s such a huge battle when you’re dealing with so many notes. I think both [director] Wil Shriner and I felt pretty beat up at the end of the process.” The film didn’t do well theatrically, but it did better on DVD. “I think it’s always good for the author to stay a good cattle prod’s distance from the actual moviemaking,” notes Hiaasen ruefully.

___________________________________

Music Bonus

___________________________________

Music is a huge part of Hiaasen’s novels. “It says a whole lot about a character if you say what kind of music he or she is listening to,” he says.

Music references are everywhere, from Tourist Season’s “Sympathy for the Devil” to Double Whammy’s “Nights in White Satin” to the carefully selected dance tracks of Strip Tease (not only those of the strip club, but those of the crosstown punk bar, the Gay Bidet, featuring such groups as the Crotch Rockets, Cathy and the Catheters, and the Fabulous Foreskins) to Skink’s hallucinated duets in Skinny Dip, not only the aforementioned Eydie Gorme and Cat Stevens, but David Lee Roth and Sophie Tucker, and Bobbie Gentry and Placido Domingo.

Sometimes music acts as an important barometer of character: In Skin Tight, Mick Stranahan explains to a young woman why a relationship between them wouldn’t work. “Name the Beatles,” he says. She falters at George Harrison. A later love interest, however, rattles all four right off, then says, “and Pete Best.” It’s a match. Stranahan does the same to Joey Perrone in Skinny Dip, and she also passes. In Lucky You, African-American lottery winner JoLayne Lucks gives would-be helper Tom Krome a skeptical look and asks him to name off some black musicians. He passes with Marvin Gaye, Jimi Hendrix, B. B. King, Al Green, Billy Preston, and “the Hootie guy.”

Sometimes entire plots revolve around music. In Basket Case, the mystery at the center of the book is the “accidental” death of Jimmy Stoma, of the legendary band Jimmy and the Slut Puppies. Supporting characters include his steely one-hit-wonder wife Cleo Rio, and a record producer who confuses the Black Crowes with Counting Crows, and claims he worked with “Matchbox Thirty.” In Star Island, Cherry Pye’s music world drives everything, and so does the music, including that of Lady Gaga, Lenny Kravitz, Britney, Beyonce, and, um, Presley Aaron. What—you don’t know that singer’s hot song, “Daddy, What’s My New Momma’s Name”? Where have you been?

And sometimes the music revolves around the plots. Jimmy Buffett wrote a song called “The Ballad of Skip Wiley,” after the provocateur of Tourist Season. In Australia, a band named itself the Sick Puppies (and Sick Puppy itself featured a dog named McGuinn. If you don’t know who that is, I’m sorry, we have nothing to talk about). And for Basket Case, Carl Hiaasen actually wrote a song with the legendary Warren Zevon, which not only appeared in the book, but on Zevon’s album My Ride’s Here.

A sample verse:

She’s manic-depressive and schizoid, too

The friskiest psycho that I ever knew

We’re paranoid lovers lost in space

My baby’s a basket case

Upon occasion, Hiaasen has kept an acoustic guitar in his study, and when he feels blocked, “bangs the hell out of the guitar.” He has also played once in a while with the celebrated Rock Bottom Remainders, a band composed exclusively of writers such as Dave Barry, Amy Tan, Ridley Pearson, and Stephen King. Unfortunately, Barry says, “Playing guitar is the one thing Carl can’t do well. I remember one time we were playing and Carl brought his guitar teacher along and the two of them were at the back and you could hear in every song the teacher yelling, ‘C, Carl! Now, A!

___________________________________

SQUEEZE ME Bonus

___________________________________

The following is an exclusive excerpt from Carl Hiaasen’s upcoming book, Squeeze Me (Knopf, September 29, 2020).

On the night of January twenty-third, unseasonably calm and warm, a woman named Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons disappeared during a festive charity gala in the exclusive island town of Palm Beach, Florida.

Kiki Pew was seventy-two years old and, like most of her friends, twice widowed and wealthy beyond a need for calculation. With a check for fifty thousand dollars she had purchased a Platinum D table at the annual White Ibis Ball. The event was the marquee fund-raiser for the Gold Coast chapter of the IBS Wellness Foundation, a group globally committed to defeating irritated bowel syndrome.

Mrs. Fitzsimmons had no personal experience with intestinal mayhem but she loved a good party. Kiki Pew spent little time at her table; a zealous mingler, she was also susceptible to Restless-Leg Syndrome, another third-tier affliction with its own well-attended charity ball.

The last person to interact with Mrs. Fitzsimmons before she vanished was a Haitian bartender named Robenson, who under her hawk-eyed supervision had prepared a Tito’s martini with the requisite orange zest and trio of olives speared longitudinally. It was not Kiki Pew’s first cocktail of the evening. With cupped hands she ferried it from the high-domed ballroom into sprawling backyard gardens filled with avian-themed topiary – egrets, herons, raptors, cranes, wood storks and of course the eponymous ibis, its curly-beaked shadow elongated on the soft lawn by faux gaslight lanterns.

Alone with her vodka, Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons wended through the maze of bird shrubbery toward a spleen-shaped pond stocked with bright goldfish and bulbous koi. It was upon that silken bank where Kiki Pew’s beaded clutch would later be discovered along with her martini glass and a broken rose-colored tab of Ecstasy.

It appeared that Mrs. Fitzsimmons had consumed half the tablet and either decided to have a swim, or accidentally fell into the pond.

Shore divers were summoned. Groping through the brown muck and fish waste, they recovered numerous algae-covered champagne bottles, the rusty keys to a 1967 Coupe DeVille, and a single size-5 Louis Vuitton cross-pump, which the McMarmots somberly identified as the property of their missing friend.

Yet the corpse of Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons wasn’t found, which perplexed the police due to the confined location. They asked Mauricio, the supervisor of the grounds-keepers, to watch the pond for a floater.

Katherine Sparling Pew began wintering in Palm Beach as a teenager. She was the eldest granddaughter of Dallas Austin Pew, of the aerosol Pews, who owned a four-acre spread on the island’s north end.

It was there, at a sun-drenched party benefiting squamos-cell research, that Katherine met her first husband. His name was Huff Cornbright, of the anti-freeze and real-estate Cornbrights, and he proposed on their third date.

Huff and Kiki Pew Cornbright settled in Westchester County, producing two trendily promiscuous offspring who made good grades and therefore needed only six-figure donations from their parents to secure admission to their desired Ivies. The family was jolted when, at age fifty-three, Huff Cornbright perished on an autumn steelhead trip to British Columbia. Swept downstream while wading the Dean River, he foolishly clung to his twelve-hundred-dollar fly rod rather than reach for a low-hanging branch and haul himself to safety.

Kiki Pew unloaded the Westchester house but kept the places she and Huff had renovated in Cape Cod and Palm Beach. The Cornbrights’ now-grown sons had found suitable East Coast spouses to help liquefy their trust funds, freeing Kiki Pew to spread her wings without feeling the constant eye of filial judgment. She waited nearly one full year before seducing her Romanian tennis instructor, two years before officially dating eligible men her age, and four years to re-marry.

The man she chose was Mott Fitzsimmons, of the asbestos and textile Fitzsimmons’. A decade earlier he’d lost his first wife to an embolism while parasailing at Grand Cayman. Among prowling Palm Beach widows Mott was viewed as a prime catch because he was childless, which meant less holiday drama and no generational drain on his fortune.

He was lanky, silver-haired, seasonally Catholic and steeply neo-conservative. It was Kiki Pew’s commiserative coddling that got him through the Obama years, though at times she feared that her excitable spouse might physically succumb from the day-to-day stress of having a black man in the Oval Office. What ultimately killed Mott Fitzsimmons was nonpartisan liver cancer, brought on by a stupendous lifetime intake of malt scotch.

Kiki Pew was consoled by the fact that he survived long enough to relish the election of a new president who was reliably white, old and scornful of social reforms. After Mott’s death, with his croaky tirades still ringing in her bejeweled ears, Kiki Pew decided to join the Potus Pussies, a group of Palm Beach women who proclaimed brassy loyalty to the new, crude-spoken commander-in-chief. For media purposes they had to tone down their name or risk being snubbed by the island’s PG-rated social sheet, so in press releases they referred to themselves the Potussies. Often they were invited to dine at Casa Bellicosa, the winter White House, while the President himself was in residence. He always made a point of waving at them from the buffet line or pastry table.

News of Kiki Pew’s disappearance at the IBS gala swept through the Potussies like norovirus on a Carnival cruise. The group’s co-founder – Fay Alex Riptoad, of the ethanol and hedge-fund Riptoads – immediately dialed the private cell phone of the police chief, who assured her that no resources would be spared in the effort to solve the case.

That evening, the Potussies gamely dressed up and gathered at Casa Bellicosa. They left an empty chair where Kiki Pew Fitzsimmons usually sat, and ordered a round of Tito’s martinis in her honor. Other club members stopped by the table to express support and seek updates.

“Oh, I’ll bet our little Keek is just fine,” one man said to Fay Alex. “She probably got confused and wandered off somewhere. My dear Ellie does that from time to time.”

“Your dear Ellie has Stage 5 dementia. Kiki Pew does not.”

“The onset can be subtle.”

Fay Alex said, “Let’s all stay positive, shall we?”

“But I am,” the man replied, canting an eyebrow. “Being mixed-up and lost is positively better than being dead at the bottom of a fish pond, no?”

(Excerpted from SQUEEZE ME by Carl Hiaasen. Copyright © 2020 by Carl Hiaasen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.)

___________________________________

ONE FINAL BONUS:

A NOTE FROM CARL HIAASEN, ON SQUEEZE ME

___________________________________

From Carl Hiaasen:

Obviously, the headlines today provide plenty of satiric inspiration, especially in South Florida.

I’m sure some people will assume that one of the main characters in this novel is based on Donald Trump, but in reality he could be any volatile, cheeseburger-loving president who has a winter home in Palm Beach. As for the wild pythons—which also play a major role—I’ve been following their ravenous romp through the Everglades for decades. I figure it’s only a matter of time before what happens at the beginning of SQUEEZE ME actually happens in true life.