When I was in high school, a friend invited me for Sunday services at the church where her father was pastor. There was much that intrigued me (including the fact that her mother had been “saved” in this church—and could never again wear pants). It didn’t occur to me to ask what religion they belonged to—I jumped at the chance to visit a place I’d secretly come to associate with belonging and authenticity. You couldn’t really be Black in my all-Black Long Island neighborhood unless you went to church—period. My block formed the north side of a cul-de-sac loop, where the houses were green and evenly-shingled and pleasant; on the south side, the homes seemed shabby and unmown and were quietly referred to as “welfare.” The one thing I saw at every house (besides ours) was a direct footpath from front step to a place of worship, and thus a connection to a larger, ideal community.

I hadn’t been raised with religion; both my parents were card-carrying atheists who wouldn’t allow a single “God bless you” to be uttered after a sneeze (for the record, I grew up saying, “Gesundheit”). Add to this the fact that my mother was white and German, and that my Black father thought himself above the deluded fray. Religion would poison my mind, he said, seemingly pleased with our outsider status. (Forget the fact that in my eyes, the idea of belonging to a church meant being part of something good and powerful. It meant comfort and vigilance.) From our living room window I’d watch girls in houndstooth coats and patent leather shoes make their way into cars that would safely spirit them off to the Hollywood Baptist or Bethel A.M.E, where (I imagined) they celebrated and sang and recited verses from their children’s Bibles and admired each other’s Sunday beauty and skilled obedience.

I wanted in on that. I wanted nice clothes (mine were in tatters) and pleasing hair (to my great chagrin, my head required neither a hot comb nor a box of relaxer). Girls at my school—whether getting ready to take a surprise quiz or kick someone’s ass in the school parking lot—often proclaimed that God made all things possible for them. Church was the family I wished I could have but didn’t; of course, I never connected the dots of my religious fantasy to my fractured life at home. The only thing my unhappy parents agreed on (besides an enduring hatred of Richard Nixon) was that there was no such thing as God. One Christmas I bravely asked for my own children’s Bible—illustrated!!—but was laughed to scorn: a Bible would only poison my mind, my father said. And why, for heaven’s sake (no pun intended), would I want to poison my mind? We weren’t those kind of people. (Yes, exactly my point.)

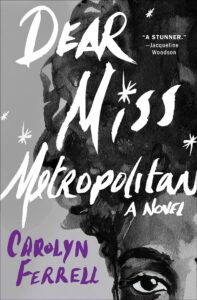

When I began to write my novel Dear Miss Metropolitan, I wasn’t at all thinking about church. I wasn’t even thinking about my own lived experience, and how that was possibly translating itself into my fiction. The idea of belonging, of forming a necessary community, seemed crucial to the vision I had for my characters. I had started out believing I was going to write a straightforward narrative of three young girls who’d been kidnapped, held prisoner and tormented, and then set free. Beginning, middle and end, a linear narrative, boom, done. But after completing that first draft, the story felt incomplete, even forced. In the background, my characters’ voices swirled in my writer’s brain, making subtle connections, surprising me with delicate insights. I needed to listen to what they were really saying. As the “victim-girls,” Gwinnie, Fern and Jesenia tell each other stories as a means of protection and survival. Storytelling becomes both curative and redemptive. Early on, Gwinnie mentions something her stepfather said (in defiance of her zealous mother): “Religion is just between a man and his God, and that’s as it should be.”

When we got to my friend’s church, all those years ago, my friend and I were greeted by stately-coiffed women who guided us to a front pew, in direct view of her father, who sat on something resembling a throne. Services began; four hours later, I asked my friend: when is church over? Not that I wasn’t enjoying myself (there was, unfortunately, an Everest pile of homework waiting for me at home). I didn’t let any worry ruin my day, though, as the experience of this church was completely engaging: I desperately lip-synched to the hymns that ranged from sweet and soulful to devout and endless; I sympathized with the several women who fell down in the pews, catching the spirit, later arising as drenched as if it had rained indoors. I tried my hardest to fit in, though I could not recite one single verse from the Bible. During a break, when asked by those stately church mothers if I’d been baptized, I skillfully wove a tale (read: lie) about the church my father had been forced to attend as a child—Jones Hill Baptist in Spring Hope, North Carolina—and attempted to make it seem as if I attended that same church each week. People liked my interest. They felt sorry for me but also somewhat encouraged. And I started to feel good that Sunday, as if I might have indeed started walking that same footpath from my front step to the doors of this ideal community. Stretching the truth hadn’t cost me a single ounce of worry.

It was precisely this idea of belonging that fueled me as I revised my characters in Dear Miss Metropolitan. There was a kind of religion in each of the characters, organized by their hopes and needs, a perfect foil to the world that seemed to fight against them at every turn. Their religion was rooted in belonging, protection, healing and compassion—something these three unguarded Black and Brown girls had received neither from their families nor from their extended communities. Their religion—not unlike the religions they’d experienced earlier—was based on a kind of storytelling that would hopefully restore their humanity, ascribe meaning to their lives.

To belong is to create a world where you can exist. A world where, quite possibly, you can thrive.To belong is to create a world where you can exist. A world where, quite possibly, you can thrive. The circumstances of belonging may inadvertently harm you, but that harm is small in proportion to the perceived benefits of community and agency. A linear form could not hold the novel’s full story; indeed, its shape grew to include not only narrative but newspaper articles, fairy tales, photographs, letters, religious commentaries, dreams, official and unofficial histories. This combination shattered the initial (and more conventional) form of the book; most importantly, it allowed my characters to determine a world of their own making—as an act of survival and resilience. While in captivity, Fern, Gwinnie and Jesenia gave up on conventional notions of family, church and school. They even had to reinvent food. They use humor to deal with the unlivable conditions around them, to process the inhuman demands made of them. This reformulation of reality welcomed their imaginations and idiosyncratic worldviews which in turn meant: they would keep on moving.

From the start of my writing process, I understood I wasn’t going to write about actual events, or about people who were still alive—though all around me, there were crimes against vulnerable Black and Brown girls that broke my heart. True crime was one catalyst for my novel—not the basis, but a grim sort of inspiration; and behind that was my desire to reclaim their lives from the trash heap of history. According to recent statistics from the Congressional Black Caucus, Black women and girls represent 40% of sex trafficking victims; there are some 64,000 Black women missing in the US, according to FBI data gathered by the Black and Missing Foundation. In 2018, the Women’s Media Center observed that African American girls make up over 40% of the missing children in America. What could I, as a fiction writer, do with this devastating information? My characters are composites of the real and imaginary, hopefully functioning in a way to bring greater attention to the plight of vulnerable girls and women of color. Humor combines with darkness to shine the spotlight on these lives in the margins.

Under the violent eye of Boss Man, my three young girls create their own communal world, built not on traditional religious parables but on stories of shared trauma. When Gwinnie, for instance, remembers her own mother’s religious fervor—one that will eventually excommunicate her own daughter—she is determined to, along with Fern, to create a world complete with its own sets of laws, its own religion—a world that will protect and nurture them as no other has before. Before captivity, Gwinnie’s religion was based on the music of Prince; now, as a prisoner of Boss Man, her religion becomes more expansive. Its charity extends to the defenseless girls beside her. Together they try to save themselves, they create their own religion, one that doesn’t exist in a book or in a building. Their community spins the traditional narrative of church on its head—not as a complaint, necessarily, but as a gesture toward agency and wholeness. When, after they are liberated, a church is built on the exact spot where they were kept hostage, there seems to be a general air of distrust toward it. Perhaps this new place of worship will provide a potential healing for the other survivors—i.e., the community members stricken by their own survivor guilt. Maybe they can start again. Maybe this time, organized religion will work better. Or maybe not. Can the outside community broaden their ideas of faith, hope and charity? Can the outside community come together to understand what the girls understand—that healing must move beyond their conventional notions of who and who doesn’t deserve to belong?

My own future in churches took varied paths after I left for college: I unwittingly joined a Dutch Reformed during the height of South African apartheid; I did indeed attend services at Jones Hill Baptist, where unforgiving memories of my father lurked in its congregants. Now and then I slipped into a Catholic mass on my way to my job in the South Bronx, pretending I comprehended all the Latin words necessary for salvation. Church has always been around me, promising great things from an idealized distance. Fern, Gwinnie and Jesenia saw through those promises and created their own church borne of urgent love and self-preservation. I suppose I eventually did the very same thing myself. What I grew to love about their church were the following rules: you are your sister’s keeper. You don’t need nice clothes to enter. Nothing will ever turn you away, not even after liberation, when most parts of your heart have been restored, and you understand yourself to be a Black/Brown woman worthy of all good things.

***